International Education Studies; Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039

Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education

60

Impact of Cornell Notes vs. REAP on EFL Secondary School Students’

Critical Reading Skills

Samah Zakareya Ahmad

1

1

Faculty of Education, Suez University, Suez, Egypt

Correspondence: Samah Zakareya Ahmad, Faculty of Education, Suez University, Suez, Egypt.

Received: June 1, 2019 Accepted: July 13, 2019 Online Published: September 29, 2019

doi:10.5539/ies.v12n10p60 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v12n10p60

Abstract

This study compared the effect of two notetaking strategies (Cornell Notes vs. REAP) on EFL secondary school

students’ critical reading skills. The Alternative Treatment Design with Pretest was used where three intact classes

of first-year EFL secondary school students were randomly assigned as a control group and two experimental

groups. All participants were administered to a critical reading skills test both before and after the treatment. For

12 weeks, participants in the control group received their regular instruction while those in the first experimental

group used Cornell Notes and those in the second experimental group used REAP. Using one-way analysis of

variance did not reveal any significant differences among the means of scores of the three groups on the pretest of

critical reading skills (f=0.36, p>0.05). However, the one-way analysis of variance indicated that significant

differences existed among the means of scores of the three groups on the posttest of critical reading skills (f=14.45,

p<0.05). Moreover, three subsequent independent-samples t-tests comparing posttest scores indicated that students

in each experimental group scored significantly higher than those in the control group (t=3.90, p<0.05; t=5.03,

p<0.05, respectively) and that there is no statistically significant difference between means of scores of students in

the two experimental groups (t=1.35, p>0.05). Therefore, it was concluded that both Cornell Notes and REAP had

a significant effect on EFL secondary school students’ critical reading skills.

Keywords: Cornell Notes, critical reading skills, EFL secondary students, REAP

1. Introduction

1.1 Background to the Problem

The 21st century information society has provided student readers with a wealth of resources which supported

them in pursuing well-founded answers to various critical issues. Nevertheless, this necessitates that students

intermingle information from sources expressing various and even contradictory points of view (Bråten &

Braasch, 2017). In other words, students are required to become critical readers.

To be a critical reader means to read critically while as well as after reading (Blakesley & Hoogeveen, 2012) in

order to synthesize, analyze, and evaluate what is read (Van Blerkom, 2012b). In contrast to literal and mechanic

reading whose aim is to obtain knowledge (Ateş, 2013), critical reading is to develop an analytical (Van Blerkom,

2012a) neutral comprehension of the text (Mayfield, 2014). It involves: distinguishing fact, opinion, and belief;

questioning the author’s intentions, argument, and word choice (Blakesley & Hoogeveen, 2012); and finding the

conclusions based on the evidence the writer put forth (Abu Shihab, 2011). Therefore, it requires readers to

comprehend not only the content of the text they are reading but also the context in which it was produced (Comber

& Nixon, 2011). In brief, critical readers read beyond what was written to how and why it was written (Rog, 2012).

Several researchers view critical reading as an important life and learning skill (e.g., Jewett, 2007; Zigo & Moore,

2004) due to many reasons. First, many employers require graduates entering the workplace to have a number of

skills including critical reading skills (Camp & Camp, 2013). Also, critical reading helps readers evaluate

arguments; consider commercials, products and advertisements; and judge policies offered by the government

(Pirozzi, Starks-Martin, & Dziewisz, 2014). Moreover, learners might be confused from the huge quantity of

information existing on the Internet (Cohen & Cowen, 2010). Therefore, they need to be taught how to find the

required information, how to connect information from different sources, and how to efficiently make use of this

information to work out problems (Leu & Kinzer, 2000).

The ability to critically read complex material is a key predictor of college success as college students need to

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

61

analyze, synthesize, and evaluate what they read. However, critical reading is not adequately developed through

schooling (Bråten & Braasch, 2017). Consequently, most EFL students entering higher education are not usually

equipped with the critical reading skills required to cope with college level reading (Lewin, 2005; Magyar, 2012;

Şen & Neufeld, 2006). A survey of recent studies tackling the problem of critical reading skills for Egyptian EFL

students showed that many of them suffer from weaknesses in critical reading (Abu Zeid, 2017; Amer, 2017;

Badawy, 2018; Bedeer, 2017; Dakhail, 2016; El-Sayed, 2019; Hanafy, 2018; Ismail, 2015; Zaki, 2014). Moreover,

the Scholastic Assessment Test

®

(SAT), critical reading section was administered to 34 EFL students at Shadia

Salama Secondary School for Girls. This pilot study revealed that those students scored very low on critical

reading skills.

1.2 Problem Statement

Based on the survey of recent research as well as the SAT result, the problem of the present study was that there

were some weaknesses in Egyptian EFL secondary school students’ critical reading skills. For the sake of finding a

solution to this problem, the researcher compared the impact of two notetaking strategies (Cornell Notes & REAP)

on EFL secondary school students’ critical reading skills.

1.3 Review of Related Literature

1.3.1 Notetaking

Notetaking is a method of writing down the essential information in a lecture, a meeting, or a reading text rapidly,

briefly, and clearly (McPherson, 2018). For a long time, taking notes has been widely used as an important learning

method (Chen, Gong, & Huang, 2015; Nielsen & Webb, 2011). The ability to take notes is one of the most effective

ways to increase students’ achievement (Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001) as it is one of the research based

strategies for: helping learners retain a greater amount of information (Macdonald, 2014), supporting their learning

independence (Brunner, 2013), saving their study time (McPherson, 2018), and helping them remain mentally

engaged while learning new and challenging material (Brunner, 2013). Therefore, notetaking should be taught as

part of the curriculum (Amini Asl & Kheirzadeh, 2016).

However, students can seldom take notes in a systematic way that supports deeper learning of content due to

inability to recognize and encode the most essential points (Brunner, 2013) while connecting the new data to

previous information for understanding (Quintus, Borr, Duffield, Napoleon, & Welch, 2012). It might also be

because most students either did not get instruction in how to take notes or received that instruction at a relatively

late point in their education (Boyle, 2007). Therefore, students need explicit instruction in notetaking (Dean,

Hubbell, Pitler, & Stone, 2012) in order to be able to improve the quality of their notes (Gray & Madson, 2007).

There are different strategies for notetaking (Macdonald, 2014) including Cornell Notes and REAP (Allen, 2008).

1.3.2 Cornell Notes

Cornell Notes is a process for taking notes during reading developed by Cornell University Professor of Education,

Walter Pauk (Miller & Veatch, 2011; Syafi’I, 2019) as a systematic method to master ideas and facts presented in a

lecture or a text (Smith, 2017). In this process, students are required to read a text, record notes including the main

ideas, reread those notes to form questions, and finally use the notes and questions to write a summary (Gunning,

2012; Honigsfield & Dove, 2013). The Cornell method involves dividing a page into three different spatial

sections: one for main ideas, another for supporting details, and a third for a summary (Crawford, 2015). They then

use this form to review, reflect on, and study their notes (Parrish & Johnson, 2010).

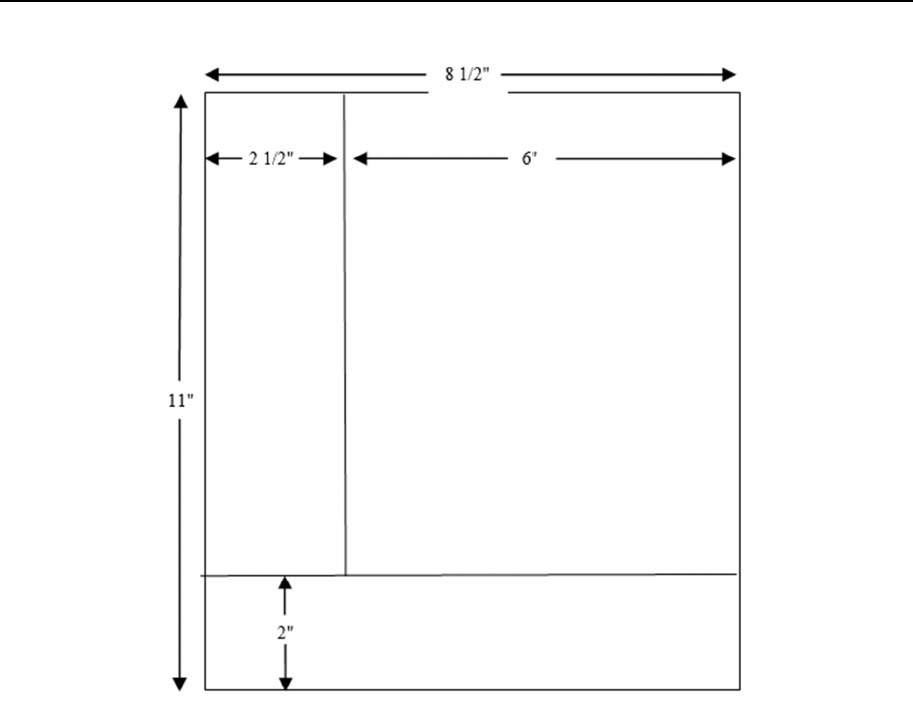

The page is divided vertically into two columns (Brooks, 2016; Fujinami, 2017); the right column is two thirds of

the page and the left column is one third of the page (Polleck, 2017; Tsai-Fu & Wu, 2010) while six or seven lines

are left at the bottom of the page (English, 2014) (See Figure 1). The primary notetaking area on the right is where

readers record their notes about the main ideas of the text while reading (Beach, Anson, Breuch, & Reynolds,

2014; Robinson, 2018). On the left column, readers put keywords, thoughts, questions, and observations about the

notes on the right column after reviewing them (Werner-Burke & Vanderpool, 2013). The area at the bottom is

preserved for a summary of what readers have learned (Donohoo, 2010). This summary allows them to use their

own words to put all the thoughts together after they have learned, recalled, and processed the information from the

lecture notes (English, 2014).

ies.ccsenet.

The Corn

e

that can b

e

2019). Th

r

reading th

e

into two c

p

aper (Br

o

reading, s

t

recording

through t

h

legible (F

o

informati

o

on the bot

t

informati

o

difficult (

C

Cornell N

o

(Johnson,

as well as

is a simpl

e

tool for o

r

encourage

2016), inc

informati

o

2009) as i

t

it in a use

f

(Burns &

org

F

i

e

ll Notes strat

e

e

more effort

fu

r

ee main step

s

e

text, student

s

olumns (Brun

n

o

e, 2013). Stu

d

t

udents write

the most imp

o

h

eir notes; und

e

o

rget, 2004).

O

o

n on the right

t

om of the pa

g

o

n is connecte

d

C

ho, 2011).

o

tes is seen a

s

2013) that ca

n

for independ

e

e

(Akintunde,

2

r

ganizing and

c

s critical refl

e

reases studen

t

o

n (Donohoo,

2

t

helps them

e

f

ul format (Fo

r

Sinfield, 201

2

i

gure 1. The C

o

e

gy takes read

e

fu

l than passiv

e

s

can be ident

i

s

start by dra

w

n

er, 2012). T

h

d

ents then wri

t

notes about f

a

o

rtant inform

a

e

rline main po

O

n the left c

o

(Brunner, 201

2

g

e (Cho, 2011)

d

to their per

s

s

an excellent

n

be easily im

p

e

nt learning (

H

2

013) time-sa

v

c

ondensing n

o

e

ction (Burns

&

t

confidence (

E

2

010). Additi

o

e

xtract the mo

s

r

get, 2004), a

n

2

). Moreover,

Internatio

n

o

rnell Notes s

h

e

rs through a

s

e

ly copying a

i

fied in that p

r

w

ing a line ver

t

h

en, two inche

s

t

e course nam

e

a

cts and detai

l

a

tion as conci

s

ints, key voca

b

o

lumn, they

w

2

). Next, stud

e

. Finally, at th

e

s

onal experie

n

notetaking str

a

p

lemented (B

r

H

onigsfield &

D

v

ing (Davoud

i

o

tes (Rashid

&

&

Sinfield, 2

0

E

vans & Shiv

e

o

nally, it is gr

e

s

t important i

n

n

d understand

w

Cornell Note

s

n

al Education St

u

62

h

ee

t

, adapted

f

s

tructured pro

c

lecture (Mor

e

r

ocess: pre-rea

t

ically on the

l

s

from the bo

t

e

, date, and to

p

l

s in the text

s

ely as possib

l

b

ulary terms,

d

w

rite key idea

s

e

nts condense

t

e

back side of

n

ces (Mcnight

,

a

tegy (Berry,

2

r

unner, 2012)

f

D

ove, 2013) i

n

i

, Moattarian,

&

&

Rigas, 2006)

0

04), facilitate

s

e

ly, 2019), an

d

e

at for those

w

n

formation fro

m

w

hy this infor

m

s

helps stude

n

u

dies

f

rom Pauk (20

c

ess of writin

g

e

head, Dunlos

k

a

ding, during-

r

l

eft side of a p

i

t

tom, students

p

ic at the top

o

on the right s

l

e (Mcnight,

2

d

ates, and peo

p

s

and questio

n

t

heir notes int

o

the paper, stu

d

,

2010) as we

l

2

014) as well

f

or whole-gro

u

n

all content

a

&

Zareian 201

that promote

s

s

student eng

a

d

allows for t

h

w

ho are new t

o

m

a text (Tho

m

m

ation is imp

o

n

ts remember

w

V

11, p. 327)

g

down infor

m

k

y, Rawson,

B

r

eading, and p

o

i

ece of paper

d

draw a horiz

o

o

f the page (P

ide of the pa

g

2

010). After r

e

p

le; and

m

ake

n

s that will w

o

o

a fou

r

-to-fiv

e

d

ents write ref

l

l

l as on what

t

as an enhanc

e

u

p and small-

g

a

reas (Forget,

2

5) learne

r

-dir

e

s

active learni

n

a

gement (Zha

n

h

e retention o

f

o

taking notes

m

son & Kal

m

o

rtant and wh

y

w

hat they rea

V

ol. 12, No. 10;

m

ation (Broe,

2

B

lasiman, &

H

o

s

t

-reading. B

d

ividing their

p

o

ntal line acro

s

auk, 2011). D

u

g

e (Johnson,

2

e

ading, stude

n

any scribbles

o

rk as cues f

o

e

sentence sum

l

ections on ho

w

t

hey found ea

e

d thinking pr

o

g

roup collabo

r

2

004). Moreo

v

e

cted (Jacobs,

n

g (Brunner, 2

n

g, Dang, &

A

f

great quantit

i

(Hayati & Jal

i

m

er, 2016), org

a

y

they have no

d (Johnson, 2

2019

2

013)

H

ollis,

e

fore

p

aper

s

s the

u

ring

2

013)

t

s go

m

ore

o

r the

m

ary

w

the

s

y or

o

cess

r

ation

v

er, it

2008)

0

12),

A

mer,

i

es of

i

lifar,

a

nize

t

ed it

0

13),

ies.ccsenet.

b

ecome

m

significan

t

(Donohoo

comprehe

n

Some edu

Greco, an

d

use it on

t

complete

s

important

recomme

n

quiz or re

c

learning p

o

1.3.3 RE

A

REAP is

Missouri-

K

about wh

a

2012). Th

e

students r

e

writing di

f

written th

r

Vacca, &

(Ruddell,

2

when the

y

Educators

steps: rea

d

2011) in o

they read

p

ersonal

u

REAP an

n

about it a

n

develop q

u

Many res

e

strategy (

B

allows for

org

m

ore efficient

t

effect on st

u

, 2010), and

s

n

sion through

cators offered

d

Kolencik (2

0

t

heir own. Mo

r

s

entences, an

d

ideas from th

e

n

ds that they c

o

c

ite in order t

o

o

wer comes

w

A

P

a notetaking

K

ansas City (

P

a

t they read (S

a

e

term REAP

e

ad the mater

i

f

ferent types

o

r

ough thinkin

g

Mraz, 2016).

2

007) and it is

y

are to comm

u

suggest that t

h

d

ing, encoding

o

rder to identi

fy

in their own

w

u

se (Powell et

a

n

otations are d

e

n

d discussing

i

u

estions about

Figure 2. R

E

e

archers addr

e

B

each & O’

b

r

i

the consider

a

in the learnin

g

u

dents’ compr

e

s

uccess (Kub

a

reading their

r

some guideli

n

0

13) suggest t

h

r

eover, Pauk

(

d

to use abbr

e

e

notes and re

c

o

ver the right

p

o

retain the k

n

w

hen students

t

strategy int

r

P

owell, Clevel

a

a

nti, 2015) in

is an acrony

m

i

al, encode th

e

o

f annotation

s

g

about the m

a

The REAP s

t

based on the

p

u

nicate inform

a

h

ere are certai

n

, annotating, a

n

fy

the main po

i

w

ords (North

e

a

l., 2012) abo

u

e

scribed in Fi

g

i

t with others

the topic, an

d

E

AP Annotati

o

e

ssed the adva

n

i

en, 2015) that

a

tion of mo

r

e

t

Internatio

n

g

process, an

d

e

hension (Fis

h

a

cak, 2017).

F

r

eflections (C

h

n

es for using

h

at teachers s

h

(

2011) advise

s

e

viations, whe

n

c

ord them in t

h

p

art of the pa

p

n

owledge the

y

t

hink and refle

c

r

oduced by

M

a

nd, Thompso

order to impr

o

m

for Read, En

c

e

gist of what

s

from several

a

terial and sh

a

t

rategy may b

e

p

remise that r

e

a

tion they ha

v

n

steps to follo

n

d pondering.

i

nts (Brunner,

e

y, 2005). In t

h

u

t the main id

e

g

ure 2, below.

F

(Powell et al.

,

d

connect this

r

o

n Types, ada

p

n

tages of the

: facilitates th

e

t

han one point

n

al Education St

u

63

d

acquire met

h

er, Frey, &

L

F

inally, it ena

b

h

o, 2011).

the Cornell

N

h

ould model t

h

s

students to s

k

n

ever possibl

e

h

e lef

t

-hand c

o

p

er and use th

e

y

wrote down.

c

t about what

w

M

arilyn Eane

t

n, & Forde, 2

0

o

ve their com

p

c

ode, Annota

t

they read int

o

perspectives,

a

ring reactions

e

used with s

t

e

aders have th

e

v

e obtained fro

m

w when using

In the first ste

2012). In the

h

e next step,

s

e

as and the aut

h

F

inally, stude

n

,

2012) in ord

e

r

eading to oth

e

p

ted from A.

M

REAP strateg

y

e

recall and s

u

of view, requ

i

u

dies

t

acognitive sk

i

L

app, 2009), a

c

b

les teachers

t

N

otes strategy.

h

is strategy wi

t

k

ip a line bet

w

e

. Also, Broe

o

lumn as soon

e

questions or

k

Finally, Joh

n

was read.

t

and Antho

n

0

12) for helpi

n

p

rehension of

c

t

e, and Ponder

o

their own

w

an

d

, finally,

p

with others (

R

t

udents worki

n

e

highest level

m

a text they

h

REAP. As its

n

p, students re

a

encoding step

s

tudents anno

t

h

or’s messag

e

n

ts ponder wh

a

e

r to check th

e

e

r reading the

y

M

anzo and U.

M

y

. It was des

c

u

mmarization

o

i

res little adv

a

V

i

lls (Forget, 2

c

hievement (

B

t

o monitor th

e

For example,

t

h studen

t

s be

f

w

een ideas an

d

(2013) advise

as possible af

t

k

ey terms on t

h

n

son (2013) b

e

n

y Manzo at

n

g readers to t

h

c

ontent withi

n

(Tiruneh, 20

1

w

ords, respond

p

onder what

t

R

oe & Smith,

n

g independe

n

l

s of attention

a

h

ave read (Tas

n

ame suggest

s

a

d a selection

o

, students rest

a

t

ate the text b

y

e

(Allen, 2008

)

a

t they have re

a

e

ir comprehe

n

y

have done (

A

M

anzo (1995,

p

c

ribed as a po

w

o

f information

a

nce preparati

o

V

ol. 12, No. 10;

004). It also

h

B

roe, 2013), s

c

e

students’ le

v

Bernadowsk

i

f

ore asking th

e

d

topics, not t

o

s them to dec

t

er reading. H

e

he left to try t

o

e

lieves that th

e

the Universi

t

h

ink more pre

c

n

that text (Br

u

1

4). It suggest

s

to the materi

t

hey have rea

d

2012; R. Vac

n

tly or with g

r

a

nd comprehe

n

s

demir, 2010).

s

, there are fo

u

o

n their own (

S

a

te the gist of

y

making not

e

)

. Different ty

p

a

d through thi

n

n

sion (Syrja, 2

A

llen, 2008).

p

. 358)

w

erful and fl

e

(Hathaway, 2

o

n from the te

a

2019

h

as a

c

ores

v

el of

, Del

e

m to

o

use

r

ease

e

also

o

self

e

real

t

y of

c

isely

u

nner,

s

that

a

l by

d

and

c

a, J.

r

oups

n

sion

r

key

S

yrja,

what

e

s for

p

es of

n

king

0

11),

xible

0

14),

a

cher

ies.ccsenet.

(Brunner,

2

REAP hel

p

each wor

d

knowledg

e

2009) as

w

b

uild a bri

d

strategies

(

and expa

n

own word

s

agendas,

a

Some ed

u

giving ea

c

text. Roja

s

the four R

E

reading st

e

topic and

t

Teachers

a

they are r

e

stem from

reread the

each stud

e

meaningf

u

example

o

What is th

(Clark, 2

0

informati

o

1.3.4 Cor

n

While ma

n

2018; Eva

n

& Musta

d

Mutia, Sy

p

ositive e

f

reading.

H

org

2

012), and en

h

p

s students re

a

d

(Clark, 201

4

e

to text infor

m

w

ell as generat

e

d

ge between t

h

(

Rojas, 2007).

n

ds students’ c

r

s

(Tasdemir, 2

0

a

nd make con

n

u

cators offere

d

c

h student not

e

s

(2007) sugge

s

E

AP stages.

M

e

p, it is sugge

t

hen ask them

a

re also recom

m

e

ading comple

students’ ow

n

materials (Cl

a

e

nt should cre

a

u

l definition. I

n

o

f each type (

B

e author’s int

e

0

14). In the p

o

o

n from the no

t

n

ell Notes vs.

R

n

y studies fou

n

n

s & Shively,

d

i, 2018; Fadh

l

afar, & Dewi

,

f

fect for Corn

e

H

owever, as fa

r

h

ances studen

t

a

d texts for di

f

4

). It also he

l

m

ation (Rojas,

e

questions to

h

e text and the

i

Additionally,

r

itical thinkin

g

0

10). It also h

e

n

ections betwe

e

d

some guidel

i

e

cards and as

k

s

ts that studen

t

M

ore guideline

sted that teac

h

to

r

ead and fi

l

m

ended to all

o

x texts (Syrja

,

n

thoughts (Po

w

a

rk, 2014). M

o

a

te a personal

v

n

the annotati

o

B

runner, 2012

)

e

ntion? What i

s

o

nde

r

ing step,

t

e cards (Brun

Figure

R

EAP on Criti

n

d a positive e

f

2019; Nuraen

i

l

i, 2015; Fad

h

,

2016; Santi,

e

ll notes (e.g.

,

r

as the resear

c

Internatio

n

t

s’ abilities to

w

f

ferent purpos

e

l

ps them inte

r

2007) which

e

further under

s

i

r own words

(

REAP incorp

o

g

(Brunner, 20

e

lps them dra

w

e

n the text bei

n

i

nes for using

k

ing them to

u

t

s fill in the se

c

s are introduc

e

h

ers begin by

l

l in the “R” s

e

o

w opportuniti

e

,

2011). Durin

g

w

ell et al., 201

2

o

reover, Este

v

v

ocabulary lis

t

o

n step, teache

r

)

. Teachers ar

e

s

the problem

p

the class sho

u

n

ner, 2012).

3. REAP Cha

r

i

cal Reading

f

fect for Corn

e

i

, 2019) or R

E

h

li & Suhaimi

,

2015; Zasria

n

,

Jacob, 2008)

c

her knows, n

o

n

al Education St

u

64

w

ork in group

s

e

s (Rojas, 200

7

r

act with the

e

nables them t

o

s

tanding (Roja

(

Hathaway, 20

o

rates higher

o

12) as it help

s

w

conclusions,

m

n

g read and te

the REAP st

r

u

se the cards t

o

c

tions of a cha

r

e

d for carryin

g

having a disc

u

e

ction of the c

e

s for student

s

g

the encodin

g

2

) and student

s

v

es and Whitte

t

where he/sh

e

r

s should expl

a

e

also advised

p

resented in t

h

u

ld be divide

d

r

t, adapted fro

e

ll Notes (e.g.,

E

AP (e.g., Am

a

,

2017; Juniar

d

n

ita, 2016) o

n

or REAP (e.

g

o

study comp

a

u

dies

s

(Marantika

&

7

) without ha

v

text (Tirune

h

o

answer ques

s, 2007). Mor

e

14) as well as

h

o

rder thinking

s

them synthe

s

m

ake inferenc

e

xts read in th

e

r

ategy. For e

x

o

restate what

r

t (Figure 3) r

e

g

out each ste

p

u

ssion starter

t

hart with the

t

s

to check thei

r

g

step, it is im

p

s

should be ab

l

n (2014) sug

g

e

adds any ne

w

a

in different t

y

to prompt st

u

h

e passage?

W

d

into small g

r

m Rojas (200

7

Domenico, El

a

lia, Inderawa

t

d

i, Suharjito,

A

n

reading co

mp

g

., Fitriastuti,

2

a

red the impa

c

V

&

Fitrawati, 2

0

v

ing to underst

a

h

, 2014) and

c

tions on that t

e

e

over, this str

a

h

elps them ini

t

and analysis (

P

s

ize the autho

r

e

s, evaluate id

e

e

past (Rojas,

2

x

ample, Brun

n

they want to

r

e

flecting their

r

p

of the REAP

t

o make stud

e

t

itle and the a

u

r

understandin

g

p

ortant for th

e

l

e to paraphra

s

g

est that durin

g

w

or unfamilia

r

y

pes of annota

t

u

dents with so

W

hat are some

p

r

oups for the

p

7

)

ish-Piper, Ma

n

t

i, & Erlina, 2

0

A

ndayani, 20

1

mp

rehension, l

e

2

013; Pohton

g

c

ts of Cornell

N

V

ol. 12, No. 10;

0

13). Moreov

e

a

nd the meani

n

c

onnect their

e

xt (Lapp & F

i

a

tegy helps stu

d

t

iate self-corr

e

P

owell et al.,

2

r

’s thoughts in

e

as, identify h

i

2

007).

n

er (2012) su

g

r

emember fro

m

r

esponses to e

a

strategy. As f

o

e

nts think abo

u

u

thor (Allen, 2

g

particularly

w

e

ideas genera

t

s

e without hav

i

g

the encodin

g

r

word along

w

t

ions and displ

a

me questions

p

ossible soluti

o

purpose of s

h

n

derino, &

L

’

A

0

18; Cahyanin

g

1

9; Mehmet,

2

e

ss studies fo

u

g

, 2012) on c

r

N

otes vs. RE

A

2019

r

, the

n

g of

prior

i

sher,

d

ents

ction

2

012)

their

i

dden

gests

m

the

a

ch of

o

r the

u

t the

0

08).

w

hen

ed to

ng to

g

step

w

ith a

a

y an

(e.g.,

o

ns?)

a

ring

A

llier,

g

tyas

2

010;

u

nd a

r

itical

A

P on

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

65

critical reading. Therefore, the researcher decided to compare the impacts of Cornell Notes vs. REAP on EFL

secondary school students’ critical reading skills.

1.4 Hypotheses of the Study

1) No statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in EFL secondary school students’ means of

scores in the critical reading skills posttest among the three groups (the control group and the two

experimental groups).

2) No statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in EFL secondary school students’ means of

scores in the critical reading skills posttest between the first experimental group exposed to Cornell Notes and

the control group.

3) No statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in EFL secondary school students’ means of

scores in the critical reading skills posttest between the second experimental group exposed to REAP and the

control group.

4) No statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in EFL secondary school students’ means of

scores in the critical reading skills posttest between the first experimental group exposed to Cornell Notes and

the second experimental group exposed to REAP.

2. Method

2.1 Research Design

The design used in this study was the Alternative Treatment Design with Pretest (Salkind, 2010), an experimental

design that compares the effectiveness of two alternative treatments (Rubin & Babbie, 2017). Using this design,

the researcher randomly assigned three intact classes to three groups: one control group that received regular

instruction as well as two experimental groups (one used Cornell Notes and the other used REAP). Each group was

tested on critical reading skills before and after the experimental groups received the intervention. Differences

among the three groups in both the pretests and the posttests were calculated. Additionally, differences between

each two groups were evaluated.

2.2 Variables

Two independent variables (Cornell Notes and REAP) as well as one dependent variable (critical reading skills)

were included in the study. They are operationally defined as follows:

2.2.1 Cornell Notes

Cornell Notes is a strategy for taking notes from the reading material that consists of: dividing a sheet of paper into

three parts, previewing the reading material, recording notes about important details on the right column, reducing

them into main ideas and key words in the left column, summarizing the main ideas on the bottom of the page,

reflecting on them, and reviewing them from time to time.

2.2.2 REAP

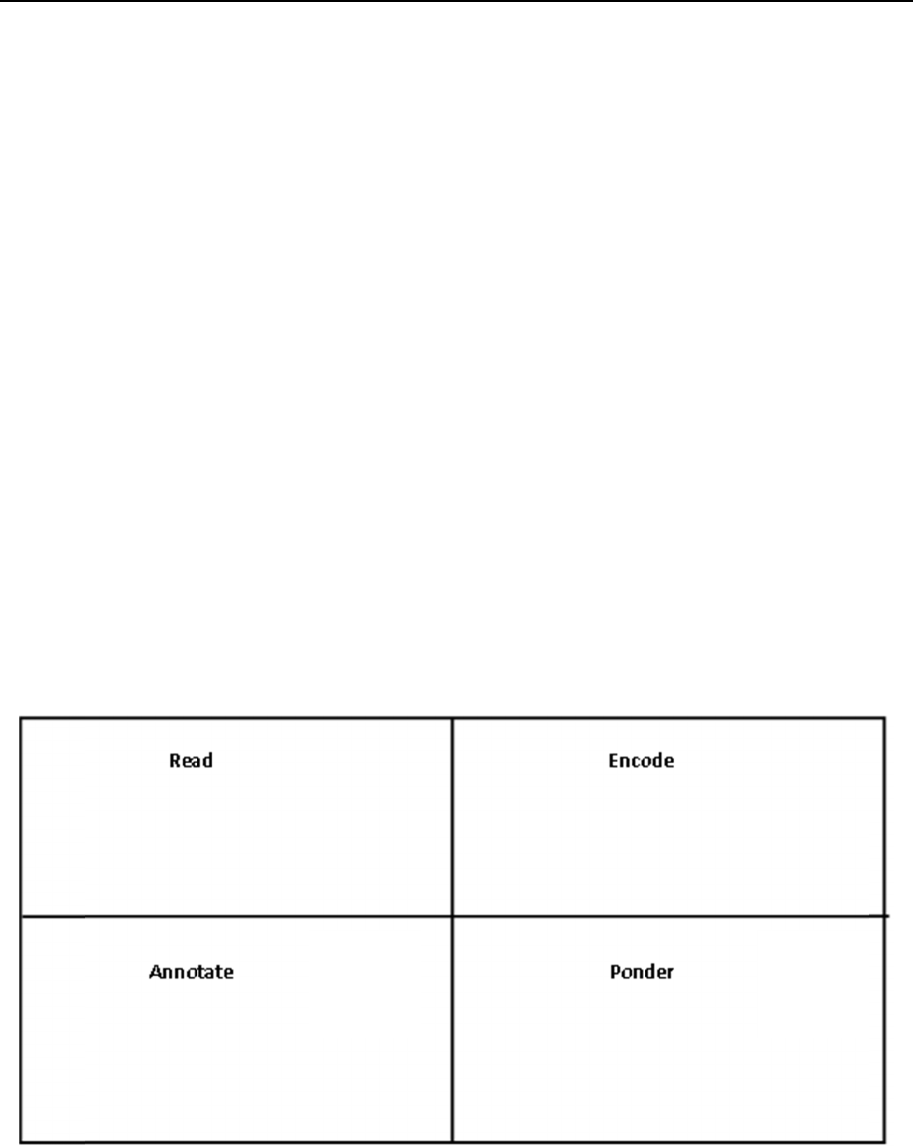

REAP is a strategy for taking notes from the reading material that consists of: dividing a blank sheet of paper into

a window-shaped organizer of four quadrants, previewing the reading material, reading it to write the title and the

author in the “R” section, putting the gist of what was read in the “E” section, writing at least three different

annotations in the “A” section, writing about what was learned from the text in the “P” section, and presenting and

discussing the notes in class.

2.2.3 Critical Reading

Critical reading is EFL secondary school students’ ability to: determine the central claim of the text, decide the

audience of the text, infer omitted words, anticipate the author’s attitude towards particular issues, identify the use

of irony and humor in a text, identify exaggeration, identify solutions to problems in the reading text, guess the

author’s intended meaning, distinguish fact and opinion, examine the evidence the text employs, make judgments

about context, and find ambiguity.

2.3 Participants

Participants were 123 students at three intact classes of first-year EFL secondary school students at Shadia Salama

Secondary School for Girls, Suez Governorate, Egypt. The three classes were randomly assigned as groups of the

study. The first class was assigned to the control group (n=42 students), the second to the first experimental group

using Cornell Notes (n=40), and the third for the second experimental group using REAP (n=41). Participants

ranged between 15-16 years of age and spent at least 9 years learning English.

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

66

2.4 Measure

A test of critical reading skills was prepared by the researcher. Twenty-four multiple-choice questions were

included in the test along with five reading passages. Three passages were followed by four questions and two

passages were followed by six questions. Each question had four options. Questions covered the 12 skills

mentioned above in the operational definition of critical reading, two questions for each skill.

The total score of the test was 24 points. Criterion validity was achieved by administering the test along with the

SAT Critical Reading Test, to a group of first-year EFL secondary school students. Pearson’s Coefficient of

correlation between students’ scores on the devised critical reading test and their scores on the SAT was 0.77

(significant at the 0.01 level). For reliability, the test was administered twice, with a two-week interval. Pearson’s

Coefficient of correlation between students’ scores on the two administrations was 0.83 (significant at the 0.01

level).

2.5 Procedures

Procedures were carried out during the first term of the 2016/2017 academic year. These procedures were divided

into four consecutive stages: 1) pretesting, 2) training, 3) treatment, and 4) posttesting. First, all participants were

pretested on critical reading skills and one-way analysis of variance revealed no statistically significant differences

among the means of scores of the three groups (f=0.36, p>0.05) (See Table 1).

Table 1. One-way analysis of variance for the three groups on the pretest of critical reading skills

Source Sum of Squares Df Mean Square F Probability.

Between Groups 11.70 2 5.85

0.36 0.70

Within Groups 1957.93 120 16.32

Total 1969.63 122

After pretesting, students in each experimental group were trained in the strategy assigned to them. That is, the first

experimental group received orientation in Cornell Notes while the second experimental group received

orientation in REAP. Each group received the training during a two-hour session at the beginning of the semester.

The researcher began by introducing students in each group to the assigned strategy in depth explaining its steps

and what was expected from them during each step. She also explained its benefits and the points they should

consider while using it. The researcher modeled the assigned strategy for the students and taught them how to take

notes using it as well as how to draw the graphic organizers that would be used to record their ideas while using

each strategy. Later on, the researcher gave students weekly 15-minute training sessions over the course of the

treatment.

For 12 weeks, participants in the two experimental groups received their treatment where the first experimental

group used the Cornell Notes strategy and the second experimental group used the REAP strategy. During this

time, participants in the control group received their usual instruction. The same reading texts were used by the

three groups during the treatment. Application of both Cornell Notes and REAP is explained below.

2.5.1 Applying Cornell Notes

2.5.1.1 Creating Format

Each student divided a piece of paper into three sections by drawing a line vertically on the left side of the paper

dividing it into two columns and then drawing a horizontal line, two inches from the paper’s bottom. The left-hand

column took about one third of the writing space, leaving the remaining two thirds for the right-hand column.

Students wrote course name, date, and topic at the top of each page.

2.5.1.2 Previewing

Students previewed the reading material they were about to read, looked at the title and subheadings, and read the

first and last paragraphs. They also generated some questions they thought of as they were previewing and listed

them in the left part of the paper.

2.5.1.3 Recording

During reading, students used the notetaking column on the right part of the paper to write notes in their own

words. They recorded important facts and details in the text using telegraphic sentences, abbreviations, and

symbols instead of complete sentences. However, they recorded definitions as stated. They indicated changes in

topic with headings or by skipping a line between ideas and topics.

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

67

2.5.1.4 Reducing

After finishing reading and recording notes, students read through their notes and reduced and synthesized them in

the left column, making them as concise as they could. They wrote the main ideas, key words, and important

vocabulary. Moreover, they formulated questions based on the notes they previously wrote in the right-hand

column.

2.5.1.5 Reciting

Students covered up the notes in the right column and used the clues in the left column to recite the relevant

information. They answered the questions, defined terms, and told what they remembered about the key words. If

they had difficulty recalling the information or if their answers were incorrect, they reread their notes, covered

them, and recited over again.

2.5.1.6 Summarizing

Students summarized the main ideas into a three-to-four-sentence summary on the bottom of the page. They

frequently shared their summaries with the class. Through class discussion, they collaborated to edit peers’

summaries.

2.5.1.7 Reflecting

On the back side of the Cornell Notes sheet, students reflected on the material by asking themselves about the

significance of these facts, how they could be applied, how they were connected to students’ experiences, how they

fitted in with what they already knew, what students agreed with, what they disagreed with, which ideas were clear,

which were confusing, and what new questions they had.

2.5.1.8 Reviewing

Students rehearsed information immediately after they finished the reflecting step. Moreover, they practiced the

information several times during the week to help keep the information active and accessible in their memory. At

the end of each week, they spent at least ten minutes reviewing all their previous notes.

2.5.2 Applying REAP

2.5.2.1 Creating Format

Students created the REAP chart through dividing a blank sheet of paper into a window-shaped organizer of four

quadrants: the “R” quadrant to record the title and the author of the text, the “E” quadrant to rephrase the main

ideas in students’ own words, the “A” quadrant to put a summary of the important points, and the “P” quadrant to

record what the writer wanted the readers to learn from the text.

2.5.2.2 Previewing

The researcher divided the class into discussion groups consisting of three to five students. She showed some

pictures as well as the title of the text and asked some questions to help students build their background knowledge

about the topic. Groups discussed the topic then one member from each group told the whole class what was

discussed in her group.

2.5.2.3 Reading

Students read the text on their own to get an overall understanding of what the author was saying. Then, they wrote

the title and the author of the text in the “R” section of the chart. The researcher asked individual students to read

the text aloud and finally the researcher read the text for the class and stopped at various points to make sure that

students understood what was being read to them.

2.5.2.4 Encoding

In the “E” box, students put the gist of what they read using their own words. In the same box, they wrote some of

the difficult or new vocabulary in the text. In their small groups, students discussed the main ideas of the text and

came up with a list of what they were. After that, the researcher led a whole class discussion about the main ideas

of the text and the meaning of the difficult vocabularies with the students.

2.5.2.5 Annotating

Students read the text again and made notes for personal use about the text. From the 11 types of annotations (See

Figure 2), students were required to choose at least three annotation types to write in the “A” section. Students

returned to their small groups to discuss their annotations and to offer constructive suggestions to one another.

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

68

2.5.2.6 Pondering

Students thought about what they had read and asked themselves about the purpose of the text, what the text meant

to them, and how they could relate their personal experiences and previous readings to it. In the “P” column,

students wrote about what they learned from the text as well as the questions to be discussed in their groups. In

their small groups, students shared their ideas, facts, feelings, and questions, then made one perfect summary about

the text given to them.

2.5.2.7 Confirmation

After students had completed their REAP charts, they were invited to present their notes in front of the class. Then,

a discussion was conducted on what students have learned about the content and their personal preferences as

notetakers. Finally, the researcher gave feedback to the students, summarized the text, and gave the moral value

from it.

3. Results

Using one-way analysis of variance indicated that significant differences existed among the means of scores of the

three groups (one control group and two experimental groups) on the posttest of critical reading skills (f=14.45,

p<0.05) (See Table 2).

Table 2. One-way analysis of variance for the three groups on the posttest of critical reading skills

Source Sum of Squares df Mean Square F Probability.

Between Groups 464.09 2 232.04

14.45 .00

Within Groups 1927.39 120 16.06

Total 2391.48 122

Moreover, three subsequent independent-samples t-tests were employed to compare the differences for each two

groups. See Table 3 for the mean difference for each two groups on the posttest of critical reading skills.

Table 3. Mean difference for each two groups on the posttest of critical reading skills

Group N M S. D. t-value Probability.

Control group 42 10.79 4.05

3.90

0.00

1st Experimental Group (Cornell Notes) 40 14.15 3.75

Control group 42 10.79 4.05

5.03 0.00

2nd Experimental Group (REAP) 41 15.34 4.20

1st Experimental Group (Cornell Notes) 40 14.15 3.75

1.35 0.18

2nd Experimental Group (REAP) 41 15.34 4.20

As shown in Table 3, results from the t-tests indicated that students in the first experimental group and the second

experimental group scored significantly higher than those in the control group (t=3.90, p<0.05; t=5.03, p<0.05,

respectively). The table also shows that there is no statistically significant difference between means of scores of

students in the two experimental groups (t=1.35, p>0.05).

4. Discussion

The first hypothesis of the present study was that no statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in EFL

secondary school students’ means of scores in the critical reading skills posttest among the three groups (the

control group and the two experimental groups). One-way analysis of variance comparing the means of scores of

the three groups on the posttest of critical reading skills revealed significant differences (f=14.45, p<0.05). Based

on this result, the researcher rejected the hypothesis.

The second hypothesis of the present study was that no statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in

EFL secondary school students’ means of scores in the critical reading skills posttest between the first

experimental group exposed to Cornell Notes and the control group. An independent-samples t-test showed a

significant difference between the means of scores of the two groups (t=3.90, p<0.05). Based on this result, the

researcher rejected the hypothesis and concluded that Cornell Notes had a significant effect on the critical reading

skills of EFL secondary school students. This result might find support in the finding of Jacob’s (2008) study

which found that the Cornell Notes method helped students become better able to answer higher-level questions

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

69

and was effective when analysis, synthesis, or evaluation was required from students. An explanation for this result

is that during using Cornell Notes, students of the first experimental group analyzed, synthesized, and evaluated

what they read (i.e., they practiced critical reading). Students analyzed the text they read and wrote notes in their

own words about important facts and details in the right column and then synthesized their notes in the left column

in the form of main ideas and questions as well as a summary of the main ideas on the bottom of the page.

Moreover, they evaluated what they read through reflecting and asking themselves about the significance of the

information in the text, whether they agreed or disagreed with it, and how it could be applied.

The third hypothesis of the present study was that no statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in

EFL secondary school students’ means of scores in the critical reading skills posttest between the second

experimental group exposed to REAP and the control group. An independent-samples t-test indicated a significant

difference between the means of scores of the two groups (t=5.03, p<0.05). Based on this result, the researcher

rejected the hypothesis and concluded that REAP had a significant effect on the critical reading skills of EFL

secondary school students. This result might find support in the findings of two studies which found that students

who used REAP improved in critical reading (Fitriastuti, 2013; Pohtong, 2012). An explanation for this result is

that during using REAP, students of the second experimental group also practiced critical reading through

analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating what they read. Students analyzed the text through identifying and

discussing the main ideas and difficult vocabulary in it. Then, they synthesized them when they wrote the gist of

what they read as well as different types of annotations which they discussed in small groups. Moreover, they

evaluated what they had read by asking themselves about the purpose of the text, what they learned from it, and

how they could connect their experiences to it. This explanation goes along with the opinions of some educators

that REAP is a critical reading strategy that helps students connect with the text at a higher level (Tiruneh, 2014)

through going beyond the author’s ideas (Sejnost & Thiese, 2010) and thinking more deeply about what they read

(Fadhli, 2015) in order to analyze how the author’s attitude affects his/her writing (Hathaway, 2014) and to

evaluate the message in the text (Bean, Baldwin, & Readence, 2012). It also helps students construct deeper

meaning of the text (Sejnost & Thiese, 2010) as they build a bridge between the text and their own words to enable

them to communicate their understanding of the text (Clark, 2014) as well as draw logical conclusions based on

evidence from the text (Esteves & Whitten, 2014).

The fourth hypothesis of the present study was that no statistically significant difference (α≤0.05) would exist in

EFL secondary school students’ means of scores in the critical reading skills posttest between the first

experimental group exposed to Cornell Notes and the second experimental group exposed to REAP. An

independent-samples t-test indicated no significant difference between the means of scores of the two groups

(t=1.35, p>0.05). Therefore, the researcher accepted the hypothesis and concluded that both Cornell Notes and

REAP developed EFL secondary school students’ critical reading skills. Since students in the three groups were at

the same level of critical reading skills at the beginning of the study and performed quite differently at the end, it

can be inferred that the difference was due to the use of the two notetaking strategies: Cornell Notes and REAP.

This is supported by the assertion of Çetingöz’s (2010) and Tsai-Fu and Wu (2010) that explicit, sustained

instruction and support with notetaking help students and increase their learning quality.

5. Conclusion

In light of the results of the present study, the researcher concluded that both Cornell Notes and REAP strategies

improved the critical reading skills of EFL secondary school students.

6. Recommendations and Suggestions

The researcher recommended that: 1) secondary school teachers be encouraged to infuse the instruction of

notetaking strategies into different subjects of study, 2) developing critical reading skills be devoted more

attention, and 3) instructors teach a variety of notetaking strategies so that students can choose the one(s) that

suit(s) their learning objectives as well as the nature of the text they read. Moreover, the researcher suggested

conducting some research studies to tackle: 1) the effect of different notetaking strategies on EFL students’

listening comprehension, 2) the effect of web-supported notetaking (e.g., iREAP) on EFL students’ reading

comprehension, and 3) teachers’ and students’ attitudes towards using notetaking strategies.

References

Abu Shihab, I. (2011). Reading as critical thinking. Asian Social Science, 7(8), 209-218.

https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v7n8p209

Abu Zeid, H. (2017). The effect of using a blended e-learning program based on metacognition on developing

first year secondary school students’ critical reading & critical writing skills (Unpublished doctoral

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

70

dissertation). Minia University, Egypt.

Akintunde, O. (2013). Effects of Cornell, verbatim & outline note-taking strategies on students’ retrieval of

lecture information in Nigeria. Journal of Education & Practice, 4(25), 67-74.

Allen, J. (2008). More tools for teaching content literacy. Portland, MA: Stenhouse.

Amalia, F., Inderawati, R., & Erlina, E. (2018). Reading comprehension achievement on narrative text by using

REAP strategy. English Language Education & Literature, 3(1), 1-7.

https://doi.org/10.30599/channing.v3i1.264

Amer, A. (2017). A problem-based learning program to enhance EFL critical reading, creative writing &

problem-solving skills of secondary stage students (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Zagazig University,

Egypt.

Amini Asl, Z., & Kheirzadeh, S. (2016). The effect of note-taking & working memory on Iranian EFL learners’

listening comprehension performance. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 5(4), 41-51.

https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsp.2016.1583

Ateş, S. (2013). Critical reading & its teaching as a skill. Turkish Journal of Education, 2(3), 40-49.

Badawy, M. (2018). Evaluating & developing critical reading skills using an interactive digital storytelling

environment for third year preparatory students (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Kafrelsheikh

University, Egypt.

Beach, R., & O’brien, D. (2015). Using apps for learning across the curriculum: A literacy-based framework &

guide. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315769127

Beach, R., Anson, C., Breuch, L., & Reynolds, T. (2014). Understanding & creating digital texts: An

activity-based approach. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bean, T., Baldwin, S., & Readence, J. (2012). Content-area literacy: Reaching & teaching the 21

st

century

adolescent. Huntington Beach: Shell Education.

Bedeer, F. (2017). The effect of a brain-based learning program on developing primary stage students’ English

language critical reading skills (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ain Shams University, Egypt.

Bernadowski, C., Del Greco, R., & Kolencik, P. (2013). Using tradebooks & databases to teach our nation’s

history: Grades 7-12. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Berry, G. (2014). Literacy for learning: A handbook of content-area strategies for middle & high school teachers.

Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Blakesley, D., & Hoogeveen, J. (2012). Writing: A manual for the digital age (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth

Cengage Learning.

Boyle, J. (2007). The process of note taking: Implications for students with mild disabilities. The Clearing House,

80(5), 227-232. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.80.5.227-232

Bråten, I., & Braasch, J. (2017). Key issues in research on students’ critical reading & learning in the 21

st

century

information society. In C. Ng, & B. Bartlett (Eds.), Improving reading & reading engagement in the 21

st

century (pp. 77-98). Gateway East, Singapore: Springer Nature.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4331-4_4

Broe, D. (2013). The effects of teaching Cornell Notes on student achievement (Unpublished master’s thesis).

Minot State University, North Dakota.

Brooks, M. (2016). Notes & talk: An examination of a long-term English learner reading-to-learn in a high

school biology classroom. Language & Education, 30(3), 235-251.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2015.1102275

Brunner, J. (2012). Now I get it: Differentiate, engage, & read for deeper meaning. New York: Rowman &

Littlefield.

Brunner, J. (2013). Doing what works: Literacy strategies for the next level. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2004). Teaching, learning, & study skills: A guide for tutors. London: Sage.

Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2012). Essential study skills: The complete guide to success at university (3rd ed.).

London: Sage.

Cahyaningtyas, A., & Mustadi, A. (2018). The effect of REAP strategy on reading comprehension. SHS Web of

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

71

Conferences, 42, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184200014

Camp, D., & Camp, W. (2013). Using content reading assignments in a psychology course to teach critical

reading skills. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 13(1), 86-99.

Çetingöz, D. (2010). University students’ learning processes of note-taking strategies. Procedia Social &

Behavioral Sciences, 2, 4098-4108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.647

Chen, G., Gong, C., & Huang, R. (2015). Note-taking in pupil’s textbook: Features & influence factors. In M.

Chang, & Y. Li (Eds.), Smart learning environments (pp. 95-110). Berlin: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-44447-4_6

Cho, J. (2011). Improving science learning through using interactive science notebook (ISN). In P. Gouzouasis

(Ed.), Pedagogy in a new tonality (pp. 149-166). Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-669-4_10

Clark, S. (2014). Writing strategies for science (2nd ed.). Huntington Beach: Shell Education Corwin.

Cohen, V., & Cowen, J. (2010). Literacy for children in an information age: Teaching reading, writing, &

thinking (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Comber, B., & Nixon, H. (2011). Critical reading comprehension in an era of accountability. Australian

Educational Researcher, 38(2), 167-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-011-0022-z

Crawford, M. (2015). A study on note taking in EFL listening instruction. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & H.

Brown (Eds.), Proceedings of Japan Association for Language Teaching Conference, 21-24 November 2014.

Tokyo: JALT.

Dakhail, N. (2016). A proposed electronic information seeking model to develop secondary stage students’ EFL

critical reading & writing skills (Unpublished master’s thesis). Mansoura University, Egypt.

Davoudi, M., Moattarian, N., & Zareian, G. (2015). Impact of Cornell note-taking method instruction on

grammar learning of Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Studies in Education, 5(2), 252-265.

https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v5i2.6874

Dean, C., Hubbell, E., Pitler, H., & Stone, B. (2012). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based

strategies for increasing student achievement (2nd ed.). Alexandia, VA: ASCD.

Domenico, P., Elish-Piper, L., Manderino, M., & L’Allier, S. (2018). Coaching to support disciplinary literacy

instruction: Navigating complexity & challenges for sustained teacher change. Literacy Research &

Instruction, 57(2), 81-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2017.1365977

Donohoo, J. (2010). Learning how to learn: Cornell Notes as an example. Journal of Adolescent & Adult

Literacy, 54(3), 224-227. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.54.3.9

El-Sayed, D. (2019). A program based on brain-based learning for develop critical & creative reading skills

among preparatory stage students (Unpublished master’s thesis). Ain Shams University, Egypt.

English, J. (2014). Plugged in: Succeeding as an online learner. Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Esteves, K., & Whitten, E. (2014). RTI in middle school classrooms: Proven tools & strategies. Minneapolis,

MN: Free Spirit.

Evans, B., & Shively, C. (2019). Using the Cornell note-taking system can help eighth grade students alleviate

the impact of interruptions while reading at home. Journal of Inquiry & Action in Education, 10(1), 1-35.

Fadhli, M. (2015). The effects of read, encode, annotate, ponder (REAP) strategy, grammar translation strategy

(GT), & reading interest in reading comprehension achievement (Unpublished master’s thesis). Sriwijaya

University, Indonesia.

Fadhli, M., & Suhaimi, M. (2017). The effect of read, encode, annotate, ponder (REAP) strategy & reading

interest on reading comprehension achievement. Tarbawi, 13(2), 7-19.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Lapp, D. (2009). Meeting AYP in a high-need school: A formative experiment. Journal of

Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(5), 386-396. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.52.5.3

Fitriastuti, W. (2013). The application of the model Read, Encode, Annotate, Ponder (REAP) to improve reading

skills of the sixth grade students of SDN 01 Limestone Tulungagung (Unpublished master’s thesis).

University of Malang, Indonesia.

Forget, M. (2004). Max teaching with reading & writing: Classroom activities for helping students learn new

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

72

subject matter while acquiring literacy skills. Oxford, UK: Trafford Publishing.

Fujinami, K. (2017). Examining the effects of using picture-based summaries in a flipped classroom model

(Unpublished master’s thesis). California State University.

Gray, T., & Madson, L. (2007). Ten easy ways to engage your students. College Teaching, 55(2), 83-87.

https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.55.2.83-87

Gunning, T. (2012). Building literacy in secondary content areas classrooms. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Hanafy, M. (2018). Raising EFL learners’ awareness towards developing critical reading skills: A content-based

approach (Unpublished master’s thesis). Helwan University, Egypt.

Hathaway, J. (2014). Writing strategies for fiction. Huntington Beach: Shell Education.

Hayati, A., & Jalilifar, A. (2009). The impact of note-taking strategies on listening comprehension of EFL

learners. English Language Teaching, 2(1), 101-111. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v2n1p101

Honigsfield, A., & Dove, M. (2013). Common core for the not-so-common learner: Grades 6-12. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Ismail, M. (2015). The effect of using self-regulated learning strategies on developing English critical reading

skills of first year experimental secondary school students (Unpublished master’s thesis). Suez Canal

University, Egypt.

Jacobs, K. (2008). A comparison of two note taking methods in a secondary English classroom. Proceedings of

the 4

th

Annual GRASP Symposium, Wichita State University, 2008 (pp. 119-120).

Jewett, P. (2007). Reading knee-deep. Reading Psychology, 28(2), 149-162.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710601186365

Johnson, B. (2013). Teaching students to dig deeper: The common core in action. New York: Routledge.

Juniardi, V., Suharjito, B., & Andayani, M. (2019). Enhancing the eighth-grade students’ reading comprehension

achievement by using REAP (read, encode, annotate, ponder) strategy. EFL Education Journal, 5(2),

1321-1330.

Kubacak, C. (2017). Student perceptions of the effectiveness of AVID for college readiness (Unpublished

doctoral dissertation). Tarleton State University.

Lapp, D., & Fisher, D. (2009). Essential readings on comprehension. New York: The International Reading

Association.

Leu, D., & Kinzer, C. (2000). The convergence of literacy instruction with networked technologies for

information & communication. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(1), 108-127.

https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.35.1.8

Lewin, T. (2005, August 17). Many going to college aren’t ready, report says. New York Times. Retrieved

August 5, 2018, from http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/17/education/17scores.html

Macdonald, V. (2014). Note taking skills for everyone: Learn the strategies of effective note taking in order to

earn maximum grades today! Vancouver, Canada: Martin Knowles.

Magyar, A. (2012). Plagiarism & attribution: An academic literacies approach. Journal of Learning Development

in Higher Education, 4, 1-20.

Manzo, A., & Manzo, U. (1995). Teaching children to be literate: A reflective approach. New York: Harcourt

Brace College.

Marantika, J., & Fitrawati, F. (2013). The REAP strategy for teaching reading a narrative text to junior high

school students. Journal of English Language Teaching, 1(2), 70-77.

Marzano, R., Pickering, D., & Pollock, J. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies

for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Mayfield, M. (2014). Thinking for yourself: Developing critical thinking skills through reading & writing (9th

ed.). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

McNight, K. (2010). The teacher’s big book of graphic organizers: 100 reproducible organizers that help kids

with reading, writing, & the content areas. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

McPherson, F. (2018). Effective notetaking (3rd ed.). Willington, New Zealand: Wayz Press.

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

73

Mehmet, T. (2010). The effect of the REAP reading comprehension technique on students’ success. Social

Behavior & Personality, 38(4), 553-560. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2010.38.4.553

Miller, M., & Veatch, N. (2011). Literacy in context: Choosing instructional strategies to teach reading in

content areas for students in grades 5-12. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Morehead, K., Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K., Blasiman, R., & Hollis, B. (2019). Note-taking habits of 21

st

century

college students: Implications for student learning, memory, & achievement. Memory, 27(6), 807-819.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2019.1569694

Mutia, F., Syafar, A., & Dewi, A. (2016). Applying read, encode, annotate, & ponder (REAP) technique to

develop reading comprehension of the grade X students. English Language Teaching Society Journal, 4(1),

1-11.

Nielsen, L., & Webb, W. (2011). Teaching generation text: Using cell phones to enhance learning. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Northey, S. (2005). Handbook of differentiated instruction for middle & high schools. New York: Routledge.

Nuraeni, T. (2019). The effect of using Cornell-note taking technique to the students of reading comprehension at

the eleventh-grade students. Simki-Pedagogia, 3(3), 1-11.

Parrish, B., & Johnson, K. (2010). Promoting learner transitions to postsecondary education & work:

Developing academic readiness skills from the beginning. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Pauk, W. (2011). How to study in college (10th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

Pirozzi, R., Starks-Martin, G., & Dziewisz, J. (2014). Critical reading, critical thinking: Focusing on

contemporary issues (4th ed.). New York: Longman.

Pohtong, K. (2012). Effects of using REAP strategy in Thai instruction on critical reading & essay writing

abilities of ninth grade students. OJED, 7(1), 117-130.

Polleck, J. (2017). Expand your tool kit: Assessing students’ reading comprehension & interpretation. Rutherford

County Schools Summer Conference, July 25-26, 2017.

Powell, N., Cleveland, R., Thompson, S., & Forde, T. (2012). Using multi-instructional teaching &

technology-supported active learning strategies to enhance student engagement. Journal of Technology

Integration in the Classroom, 4(2), 41-50.

Quintus, L., Borr, M., Duffield, S., Napoleon, L., & Welch, A. (2012). The impact of the Cornell note-taking

method on students’ performance in a high school family & consumer sciences class. Journal of Family &

Consumer Sciences Education, 30(1), 27-38.

Rashid, S., & Rigas, D. (2006). E-learning & note-taking: A comparative study. Proceedings of the 5

th

WSEAS

International Conference on Education & Educational Technology, Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain,

December 16-18, 2006.

Robinson, C. (2018). Note-taking strategies in the science classroom. Science Scope, 41(6), 22-25.

https://doi.org/10.2505/4/ss18_041_06_22

Roe, B., & Smith, S. (2012). Teaching reading in today’s elementary schools (11th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

Rog, L. (2012). Guiding readers: Making the most of the 18-minute guided reading lesson. Ontario, Canada:

Pembroke.

Rojas, V. (2007). Strategies for success with English language learners. Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD.

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. (2017). Research methods for social work (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole,

Cengage Learning.

Ruddell, M. (2007). Teaching content reading & writing (5th ed.). New Jersey: Wiley.

Salkind, N. (2010). Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288

Santi, V. (2015). Improving students’ reading comprehension by using REAP (read, encode, annotate, ponder)

strategy. Journal of Linguistics & Language Teaching, 2(1), 1-7.

Sejnost, R., & Thiese, S. (2010). Building content literacy: Strategy for adolescent learner. Maryland: Corwin.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483350578

ies.ccsenet.org International Education Studies Vol. 12, No. 10; 2019

74

Şen, A., & Neufeld, S. (2006). In pursuit of alternatives in ELT methodology: WebQuests. The Turkish Online

Journal of Educational Technology, 5(1), 49-67.

Smith, A. (2017). SQ3R, Cornell notes, ApSum: The impact of three content literacy strategies on student

learning & the perceptions of these strategies held by fifth-grade teachers & students (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). Northern Arizona University.

Syafi’I, A. (2019). Students’ response of using Cornell Note Taking System (CNTS) in listening class. Journal of

English Language Teaching & Islamic Integration, 2(1), 131-145.

Syrja, R. (2011). How to reach & teach English language learners. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tasdemir M. (2010). The effects of the REAP reading comprehension technique on students’ success. Social

Behavior & Personality, 38(4), 553-560. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2010.38.4.553

Thomson, P., & Kalmer, B. (2016). Detox your writing: Strategies for doctoral researchers. New York:

Routledge.

Tiruneh, D. (2014). The effect of explicit reading strategy instruction on reading comprehension of upper

primary grade. International Journal of Education, 6(3), 81-100. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v6i3.5989

Tsai-Fu, T., & Wu, Y. (2010). Effects of note-taking instruction & note-taking languages on college EFL students’

listening comprehension. New Horizons in Education, 58(1), 120-132.

Vacca, R., Vacca, J., & Mraz, M. (2016). Content area reading: Literacy & learning across the curriculum (12th

ed.). New York: Pearson Education.

Van Blerkom, D. (2012a). College study skills: Becoming a strategic learner (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth

Cengage Learning.

Van Blerkom, D. (2012b). Orientation to college learning (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Werner-Burke, N., & Vanderpool, D. (2013). No more index cards: No notebooks! Pulling new paradigms

through to practice. In K. Pytash, R. Ferdig, & T. Rasinski (Eds.), Preparing teachers to teach writing using

technology (pp. 43-56). Pittsburg, PA: ETC Press.

Zaki, E. (2014). The effect of using electronic mind mapping on developing first year secondary stage students’

EFL critical reading skills (Unpublished master’s thesis). Ain Shams University, Egypt.

Zasrianita, F. (2016). Using of reading, encoding, annotating, & pondering (REAP) technique to improve

students’ reading comprehension. Ta’d ib , 19(2), 147-164. https://doi.org/10.31958/jt.v19i2.460

Zhang, Y., Dang, Y., & Amer, B. (2016). A large-scale blended & flipped class: Class design & investigation of

factors influencing students’ intention to learn. IEEE Transactions on Education, 59(4), 263-273.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TE.2016.2535205

Zigo, D., & Moore, M. (2004). Science fiction: Serious reading, critical reading. The English Journal, 94(2),

85-90. https://doi.org/10.2307/4128779

Copyrights