An Urban Institute

Program to Assess

Changing Social Policies

Health

Policy for

Low-Income

People in

Florida

Health

Policy for

Low-Income

People in

Florida

Debra J. Lipson

Stephen Norton

Lisa Dubay

The Urban Institute

State Reports

Assessing

the New

Federalism

An Urban Institute

Program to Assess

Changing Social Policies

Health

Policy for

Low-Income

People in

Florida

Debra J. Lipson

Stephen Norton

Lisa Dubay

The Urban Institute

Assessing

the New

Federalism

State Reports

The Urban

Institute

2100 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037

Phone: 202.833-7200

Fax: 202.429-0687

E-Mail: [email protected]

http://www.urban.org

Copyright q December 1997. The Urban Institute. All rights reserved. Except for short quotes, no part of this book may

be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record-

ing, or by information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from The Urban Institute.

This report has been prepared as part of The Urban Institute’s Assessing the New Federalism project, which has

received funding from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, the W.K. Kellogg

Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Commonwealth Fund, the Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, and the Fund for New Jersey. Additional funding is provided by the Joyce

Foundation and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation through a subcontract with the University of Wisconsin at

Madison.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to The Urban Institute or its funders.

The authors thank the many state, county, and local officials and others who participated in interviews and pro-

vided information.

About the Series

A

ssessing the New Federalism is a multi-year Urban Institute project

designed to analyze the devolution of responsibility from the federal

government to the states for health care, income security, employ-

ment and training programs, and social services. Researchers monitor

program changes and fiscal developments, along with changes in family well-

being. The project aims to provide timely nonpartisan information to inform

public debate and to help state and local decisionmakers carry out their new

responsibilities more effectively.

Key components of the project include a household survey, studies of poli-

cies in 13 states, and a database with information on all states and the District

of Columbia, available at the Urban Institute’s Web site. This paper is one in a

series of reports on the case studies conducted in the 13 states, home to half of

the nation’s population. The 13 states are Alabama, California, Colorado,

Florida, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New

York, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin. Two case studies were conducted in

each state, one focusing on income support and social services, including

employment and training programs, and the other on health programs. These 26

reports describe the policies and programs in place in the base year of this pro-

ject, 1996. A second set of case studies to be prepared in 1998 or 1999 will

describe how states reshape programs and policies in response to increased

freedom to design social welfare and health programs to fit the needs of their

low-income populations.

The income support and social services studies look at three broad areas.

Basic income support for low-income families, which includes cash and near-

cash programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children and Food

Stamps, is one. The second area includes programs designed to lessen the

dependence of families on government-funded income support, such as educa-

tion and training programs, child care, and child support enforcement. Finally,

the reports describe what might be called the last-resort safety net, which

includes child welfare, homeless programs, and other emergency services.

The health reports describe the entire context of health care provision for

the low-income population. They cover Medicaid and similar programs, state

policies regarding insurance, and the role of public hospitals and public health

programs.

In a study of the effects of shifting responsibilities from the federal to state

governments, one must start with an understanding of where states stand.

States have made highly varied decisions about how to structure their

programs. In addition, each state is working within its own context of private-

sector choices and political attitudes toward the role of government. Future

components of Assessing the New Federalism will include studies of the varia-

tion in policy choices made by different states.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

iv

Contents

Highlights of the Report 1

Overview of Florida 5

Sociodemographic 5

Economic 5

Political 6

Roadmap to the Rest of the Report 8

Setting the Policy Context 9

Overview of the State’s Health Care Agenda 9

State Health and Health Care Indicators 11

Health Care Spending and Coverage 11

Organizational Structure of State Health Programs 17

Assessing the New Federalism: Potential State Responses to Additional

Flexibility and Reduced Funding 19

General State Philosophy toward the Poor 19

Medicaid-Specific Issues 20

Providing Health Coverage for Low-Income People 21

Medicaid Eligibility 21

Other Public Financing Programs 24

Insurance Reforms 25

Financing and Delivery System 27

Commercial Managed Care 27

Hospital Market and Regulatory Issues 29

Mergers and For-Profit Conversions 29

Medicaid Provider Reimbursement (including DSH Payments) 30

Medicaid Managed Care 32

Delivering Health Care to the Uninsured Population 37

State and County Public Health Programs 37

Impact of Government Policies and Market Changes on Safety Net

Providers in Dade and Hillsborough Counties 38

Long-Term Care for the Elderly and Persons with Disabilities 45

Supply, Expenditures, and Utilization 45

Long-Term Care for the Elderly 47

Younger People with Disabilities 50

Challenges for the Future 53

Notes 57

Appendix: List of People Interviewed 61

About the Authors 65

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

vi

Highlights of the Report

H

ealth policy issues have been a priority for Florida under the leader-

ship of Governor Lawton Chiles. The Florida Health Security Plan,

which Governor Chiles proposed in 1992 and which was ultimately

rejected by the state legislature, represented an expansion of insur-

ance coverage together with a managed competition approach to controlling

health costs. Governor Chiles was successful in winning passage of insurance

reforms in the private insurance market. In 1997, the governor made expan-

sion of coverage to children through Medicaid and the state’s Healthy Kids

Program his top health priority. He also brought suit against the U.S. govern-

ment to seek relief from changes in welfare laws that affected many legal non-

citizens in Florida and opposed the formula for distributing federal block grant

funds in 1995 because of its likely negative impact on the state of Florida.

Florida has a number of health care problems. It has one of the highest un-

insured rates in the country, 19.2 percent (vs. 15.5 percent for the nation). Per

capita spending on Medicaid ranks as one of the lowest in the country (46th

nationally) despite having the fourth largest Medicaid enrollment, about 2.2

million. The state ranks near the bottom (i.e., worst) on a number of measures of

health status, including the number of premature deaths per capita, prevalence

of cancer, number of AIDS cases, and rate of violent crime.

Medicaid enrollment and expenditure growth accelerated in the 1990s.

Between 1990 and 1995, enrollment grew by 12.7 percent annually, expendi-

tures, by 18.7 percent. Spending grew by 27.2 percent between 1990 and 1992,

and by 13.4 percent per year between 1992 and 1995. Florida’s eligibility stan-

dards remain low by national standards. In 1994, 39.6 percent of the low-

income population below 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) had

Medicaid coverage compared with 51 percent nationally. The state has a some-

what restrictive benefit package and spends less per enrollee than the national

average for all eligibility groups except children. Expenditures on long-term

care are low despite a large elderly population. The number of nursing home

beds per elderly person is well below the national average, and there is minimal

coverage of home and community-based services.

Managed care is the cornerstone of the state’s efforts to control Medicaid

acute care expenditures. Florida now contracts with 19 health maintenance

organizations (HMOs) and has implemented a primary care case management

program (MediPass) throughout the state. The state now requires mandatory

enrollment in managed care for most recipients—two-thirds of Medicaid bene-

ficiaries are in either MediPass or capitated managed care plans. Florida has

had a history of marketing and enrollment abuses and problems with quality

of care in managed care programs. Recently, the state prohibited direct market-

ing, increased resources for beneficiary education, and added staff to monitor

quality of care. It has also enacted a competitive bidding system to drive down

capitation rates, hoping to reduce rates to 92 percent of fee-for-service rates.

The state also faces problems resulting from the impact of recent welfare

reform legislation on future legal immigrants. At the time of the site visit, it was

estimated that 54,000 current Supplemental Security Income (SSI) recipients in

Florida would lose their SSI and Medicaid benefits, and another 3,062 immi-

grants who were receiving Medicaid were also expected to lose coverage. The

state filed suit asking the federal court to declare that denying SSI and food

stamp benefits to otherwise eligible, lawful, permanent resident aliens is uncon-

stitutional. Legislation was introduced by the Dade County delegation to main-

tain coverage for these individuals at state or local expense. The cost to the state

(or to local areas) was estimated at $222 million. While the Balanced Budget

Act of 1997 ensures that most of these individuals will retain their benefits,

future immigrants will not be covered.

To reduce the number of uninsured children, the governor has proposed

expanding Medicaid to cover children ages 0 to 3 old years in households with

income up to 185 percent of the FPL. The state is also expanding its Healthy

Kids Program. The Healthy Kids Program is a school enrollment–based insur-

ance program that currently provides comprehensive health insurance coverage

to 26,400 children. Additional funding has been granted to increase the number

of children in the program to 60,000. The legislature recently granted the

Agency for Health Care Administration the authority to seek a Section 1115

waiver to cover children in households with income up to 185 percent of the

FPL through the Healthy Kids Program. The cost of the program averages about

$600 per child. The program is able to keep the costs below Medicaid because

of limits on the number of plans, because of some restrictions on benefits, and

because the population served is relatively healthy.

Florida has enacted a series of insurance reforms. The reforms require insur-

ers offering policies in the small-group market to guarantee issue of policies

without regard for health status or preexisting conditions, provide for portabil-

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

2

ity of plans between employers, and require the use of modified community rat-

ing. The legislation does not affect the individual insurance market. Florida

also created 11 regional Community Health Purchasing Alliances (CHPAs) in an

attempt to reduce the costs of health insurance in the small-group market.

Currently 18,000 small businesses representing 76,000 individuals receive

coverage through the CHPAs. It appears the state is experiencing a certain

amount of adverse selection in the CHPAs. The CHPAs are also prohibited from

negotiating rates with insurers, limiting their ability to take advantage of their

market power. As a result, premiums for CHPA-sponsored insurance plans are

reportedly only about 6 percent less than premiums for the same plans offered

outside of the CHPAs.

Managed care has been growing rapidly in the private market in Florida.

As of 1995, 25 percent of the state’s population was enrolled in an HMO. Much

of the growth has been among for-profit HMOs. Although the largest HMOs

remain profitable, many of the smaller HMOs have experienced losses. As a

result, mergers and acquisitions are now occurring frequently in the commer-

cial HMO market. State policy has generally been supportive of the growth of

managed care. A number of bills to regulate managed care have been introduced

in the legislature, but to date few have been enacted. The 1997 legislative ses-

sion is expected to include increased efforts to enact legislation to set standards

for HMO practices.

The hospital market has a considerable amount of excess capacity. As a

result, HMOs and other managed care plans have successfully negotiated deep

discounts. There has also been considerable growth in for-profit hospital sys-

tems, although some nonprofit hospital systems are also developing rapidly.

However, to date there has been little impact on the number of hospitals and

number of beds. While there is concern over the implications of the growing

number of for-profit hospital beds on the provision of charity care, no action has

been taken. In fact, Columbia/HCA and the South Florida Hospital Association

have challenged the tax-exempt status of nonprofit hospitals, arguing that many

nonprofits provide little charity care but still receive tax benefits not available

to for-profit hospitals.

Safety net hospitals face significant competitive pressures as the growth in

Medicaid managed care increases the interest of private hospitals in the

Medicaid market. Nonetheless, they appear to be doing reasonably well in gen-

eral. One reason is an increase in local funding for indigent care. In both Dade

and Hillsborough Counties, local funding for indigent care has risen consider-

ably as a result of increases in sales taxes. In addition, hospitals are either devel-

oping their own HMOs or prepaid health plans, joining with other HMOs or

prepaid health plans, or developing networks with other health care providers

to achieve greater efficiencies.

Although the infusion of funds and their continuance are important to the

safety net’s success, the manner in which the funds are distributed is also

important. Hillsborough County has used the new tax revenues to fund an

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

3

insurance program that distributes funds across several types of providers.

Nonetheless, Tampa General Hospital, the major public hospital, is losing its

Medicaid patient base and is increasingly reliant on state financial support.

Dade County’s new revenues are largely targeted to Jackson Memorial Hospital,

the county’s major public hospital. These revenues are permitting the hospital

to survive the loss of Medicaid revenues. Community clinics did not receive

any of these new funds and are facing serious problems. The big question is

whether local revenues will remain adequate and continue to support care for

the indigent in these counties, as well as in other sites throughout the state.

Despite its large elderly population, Florida has relatively low expenditures

on long-term care. Long-term care is 28 percent of the state’s Medicaid budget,

compared with the national average of 34 percent. Long-term care spending is

low in Florida because its nursing home bed supply (30 beds per 1,000 people

over age 65) is one of the lowest in the country and because it has been slow to

expand home and community-based services. The state now has a few home

and community-based waiver programs and is experimenting with increases

in the provision of these services. Increases in expenditures for long-term care

seem inevitable but could place added pressures on Medicaid spending for

other groups.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

4

Overview of Florida

Sociodemographic

F

lorida has one of the country’s biggest and most diverse state popula-

tions. In 1995, Florida had a population of 14.1 million, which had

increased 9.5 percent since 1990, or 1.7 times faster than the growth rate

of the U.S. population (table 1). One in six people (16.2 percent) in the

state had income below the federal poverty level (FPL) in 1994, compared with

about one in seven people (14.3 percent) nationwide. Compared with the

United States as a whole, Florida has a higher proportion of Hispanics (16.5

percent vs. 10.7 percent in 1995). The Miami area is notable for its large con-

centration of Cubans. Overall, 10.0 percent of the state’s population in 1995

were immigrants, compared with 6.4 percent for the nation.

In 1995, 2.7 million people, or 16.7 percent of the state’s population, were

over the age of 65, substantially higher than the national average of 12.1 percent

and higher than in any other state. Its elderly population is also one of the

fastest growing in the country; the state projects a 35 percent growth in the

age-80-and-older population in the next 10 years. The majority of the state’s

population resides in a half dozen major urban centers (e.g., Miami/Fort

Lauderdale, Tampa/St. Petersburg, Orlando, and Jacksonville). Although the

state has large rural areas, there are very few places located more than an hour

from a medium-sized city.

Economic

Florida’s economy is healthy and growing at a faster rate than the U.S. econ-

omy as a whole. Job growth during FY 97–98 is projected to be 2.9 percent,

more than double the U.S. rate of 1.3 percent.

1

Beyond that, Florida’s state bud-

get assumes a slight deceleration of output and spending, which will result in

somewhat slower growth in its economy. The unemployment rate was slightly

less than that for the United States as a whole in 1996 (5.1 percent versus 5.4

percent). Per capita income ($23,061) is about on a par with the national aver-

age ($23,208) as was the increase in per capita income from 1990 to 1995—

20.7 percent in the state versus 21.2 percent in the nation (table 1). In part

because of the strong economy, Aid to Families with Dependent Children

(AFDC) caseloads have declined in each of the last three fiscal years, dropping

from about 220,500 families in October 1995 to 186,600 families in December

1996. These declines have continued since the implementation of the state’s

welfare reform program.

Political

Governor Lawton Chiles, a Democrat, has been in office since 1991 and won

reelection in 1994; his current term expires in 1998, and Florida law prohibits

him from running for a third consecutive term. Florida’s legislature has histor-

ically been led by Democrats, but that has changed recently. The Florida Senate

was evenly split prior to the 1994 election, when Republicans gained a majority

of the seats. In 1996, Republicans also gained majority control of the House,

with a two-seat lead (61 to 59). Republicans retained control over the Senate

in 1996 and now have a six-seat margin over Democrats (23 to 17).

Between 1994 and 1996, Governor Chiles’s relations with the split-control

legislature were marked by some tension. While there has been bipartisan sup-

port for spending on corrections and education throughout the 1990s, the leg-

islature has recently opposed some of the governor’s health initiatives. The

legislative agenda was dominated by a debate over funding priorities, cast

largely as a trade-off between social and health services versus education and

corrections. The legislature took funds proposed for Medicaid and transferred

them to corrections and education. With a change in legislative leadership and

a takeover of the House by Republicans, it was a matter of some speculation

whether the governor would be able to have any of his health initiatives

approved.

Health policy issues have been a particularly high priority of the gover-

nor. He sought passage of two pieces of legislation (the Health Care Reform Act

of 1992 [Chapter 92-33] and the Health Care and Insurance Reform Act of 1993

[Ch. 93-129]), which together promised to ensure for all Floridians “access to

a basic health care benefit package . . . by December 31, 1994.” The Health Care

Reform Act of 1992 created the Agency for Health Care Administration

(AHCA) to help ensure that that goal was reached. The Health Care and

Insurance Reform Act of 1993 provided the authority to create Community

Health Purchasing Alliances (CHPAs), fund rural health network initiatives,

and seek federal waivers to expand Medicaid eligibility to those with incomes

up to 250 percent of the FPL. Both acts included insurance market reforms.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

6

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

7

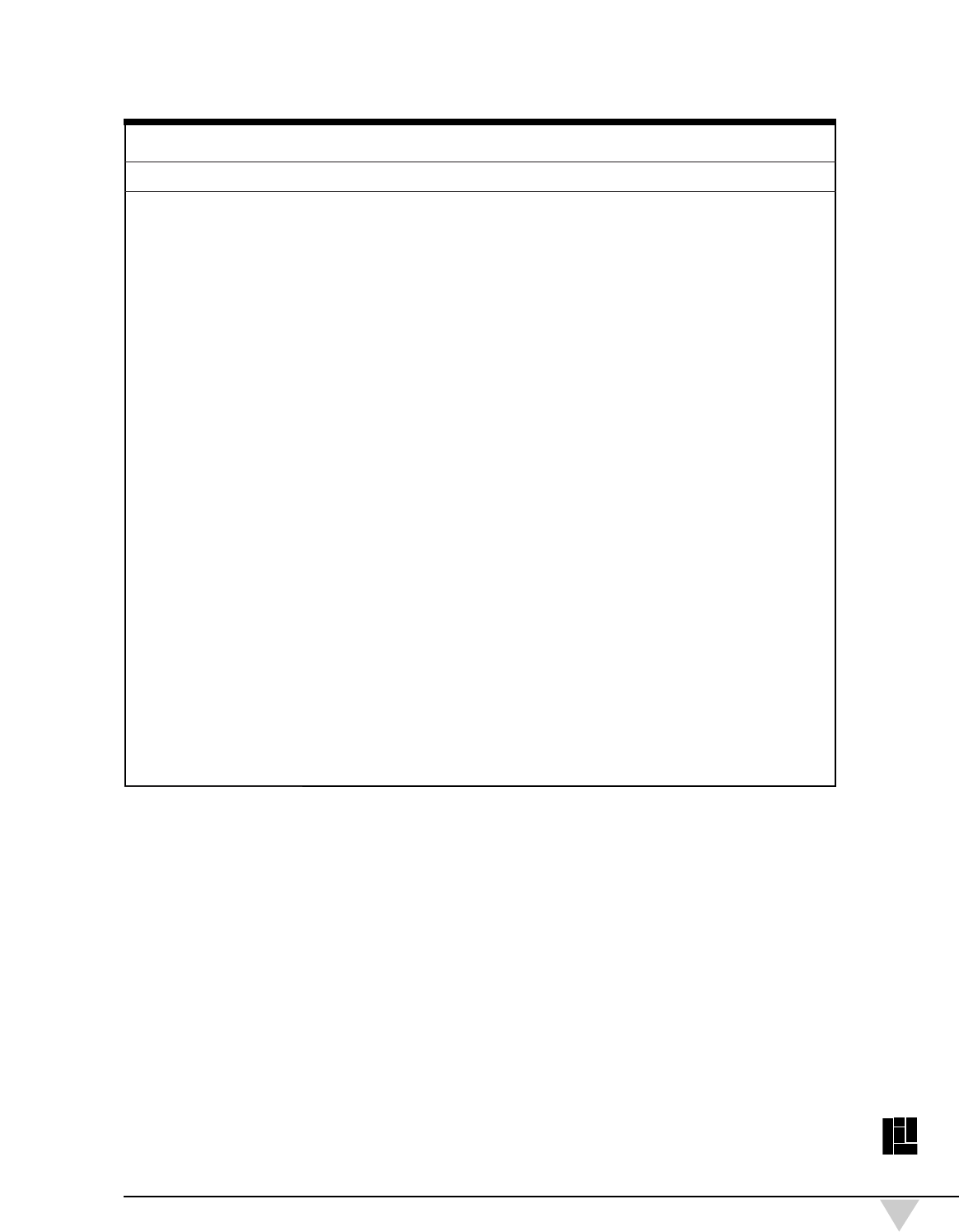

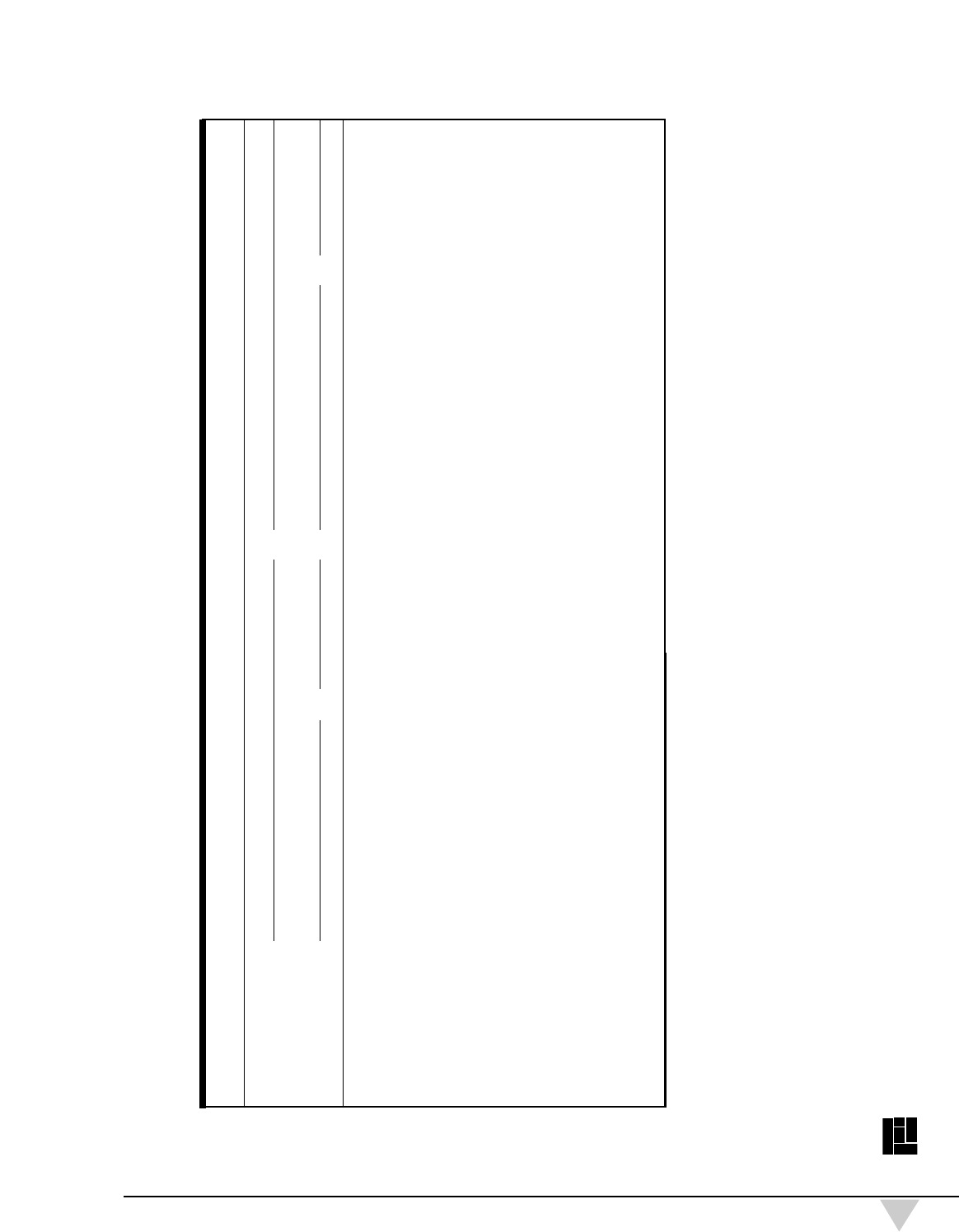

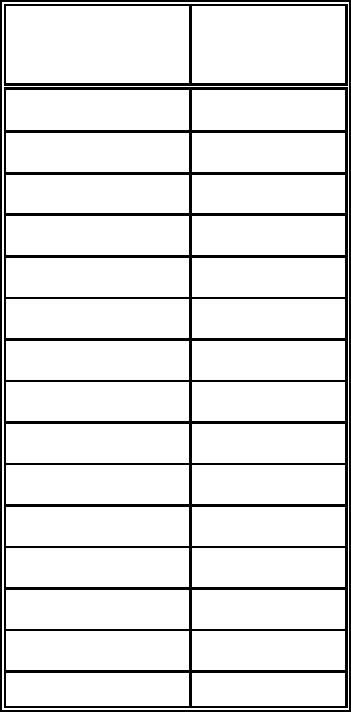

Table 1State Characteristics

Florida United States

Sociodemographic

Population (1994–95)

a

(in thousands) 14,103 260,202

Percent under 18 (1994–95)

a

24.6% 26.8%

Percent 65+ (1994–95)

a

16.7% 12.1%

Percent Hispanic (1994–95)

a

16.5% 10.7%

Percent Non-Hispanic Black (1994–95)

a

15.4% 12.5%

Percent Non-Hispanic White (1994–95)

a

66.5% 72.6%

Percent Non-Hispanic Other (1994–95)

a

1.6% 4.2%

Percent Noncitizen Immigrant (1996) * 10.0% 6.4%

Percent Nonmetropolitan (1994–95)

a

6.9% 21.8%

Population Growth (1990-95)

b

9.5% 5.6%

Economic

Per Capita Income (1995)

c

$23,061 $23,208

Percent Change in Per Capita Personal Income (1990–95)

c, d

20.7% 21.2%

Percent Change in Personal Income (1990–95)

c, e

31.3% 27.7%

Employment Rate (1996)

f, g

58.8% 63.2%

Unemployment Rate (1996)

f

5.1% 5.4%

Percent below Poverty (1994)

h

16.2% 14.3%

Percent Children below Poverty (1994)

h

25.9% 21.7%

Health

Percent Uninsured—Nonelderly (1994–95)

a

19.2% 15.5%

Percent Medicaid—Nonelderly (1994–95)

a

13.2% 12.2%

Percent Employer Sponsored—Nonelderly (1994–95)

a

59.2% 66.1%

Percent Other Health Insurance—Nonelderly (1994–95)

a, i

8.5% 6.2%

Smokers among Adult Population (1993)

j

22.0% 22.5%

Low Birth-Weight Births (<2,500 g) (1994)

k

7.7% 7.3%

Infant Mortality Rate (Deaths per 1,000 Live Births) (1995)

l

7.5 7.6

Premature Death Rate (Years Lost per 1,000) (1993)

m, n

59.6 54.4

Violent Crimes per 100,000 (1995)

o

1,071.0 684.6

AIDS Cases Reported per 100,000 (1995)

j

56.9 27.8

Political

Governor’s Affiliation (1996)

p

D

Party Control of Senate (Upper) (1996)

p

17D-23R

Party Control of House (Lower) (1996)

p

59D-61R

a. Two-year concatenated March Current Population Survey (CPS) files, 1995 and 1996. These files are edited by the Urban

Institute’s TRIM2 microsimulation model. Excludes those in families with active military members.

b. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1996(116th edition). Washington, D.C., 1996. 1995 popu-

lation as of July 1. 1990 population as of April 1.

c. State Personal Income, 1969-1995.CD-ROM. Washington, D.C.: Regional Economic Measurement Division (BE-55), Bureau of

Economic Analysis, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce, October 1996.

d. Computed using mid-year population estimates of the Bureau of the Census.

e. Personal contributions for social insurance are not included in personal income.

f. U.S. Department of Labor. State and Regional Unemployment, 1996 Annual Averages.USDL 97-88. Washington, D.C., March

18, 1997.

g. Employment rate is calculated using the civilian noninstitutional population 16 years of age and over.

h. CPS three-year average (March 1994–March 1996 where 1994 is the center year) edited using the Urban Institute’s TRIM2

microsimulation model.

i. “Other” includes persons covered under CHAMPUS, VA, Medicare, military health programs, and privately purchased

coverage.

j. Normandy Brangen, Danielle Holahan, Amanda H. McCloskey, and Evelyn Yee. Reforming the Health Care System: State

Profiles 1996.Washington, D.C.: American Association of Retired Persons, 1996.

k. S.J. Ventura, J.A. Martin, T.J. Mathews, and S.C. Clarke. “Advance Report of Final Natality Statistics, 1994.” Monthly Vital

Statistics Report; vol. 44, no. 11, supp. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1996.

l. National Center for Health Statistics. “Births, Marriages, Divorces, and Deaths for 1995.” Monthly Vital Statistics Report; vol.

44, no. 12. Hyattsville, MD: Public Health Service, 1996.

m. ReliaStar Financial Corporation. The ReliaStar State Health Rankings: An Analysis of the Relative Healthiness of the

Populations in All 50 States, 1996 edition, Minneapolis, MN:ReliaStar, 1996.

n. Race-adjusted data, National Center for Health Statistics, 1993 data.

o. U.S. Department of Justice, FBI. Crime in the United States, 1995.October 13, 1996.

p. National Conference of State Legislatures. 1997 Partisan Composition, May 7 Update.D indicates Democrat and R indicates

Republican.

The CHPAs were established in 1994, a number of rural health networks have

been certified by AHCA, and there has been significant reform in the small-

group insurance market. However, the Florida Health Security Act, the state’s

Section 1115 waiver that emerged from the 1993 act, never received funding

from the legislature.

The governor, although an ally of the Clinton administration, has not hesi-

tated to challenge federal policies that adversely affect Florida. For example,

in April 1997 he filed suit against the U.S. government, seeking relief from

changes in federal welfare laws that restrict essential federal benefits for many

legal noncitizens in Florida. He was a supporter of federal welfare reform, but

he expressed great concern about the spending caps in the 1995 Medicaid block

grant proposal. He believed the caps would be unfair to Florida and other high

population-growth states or those that had low per capita expenditures, because

those states would have a harder time finding savings.

Although it is often thought that Cubans and other Latin Americans consti-

tute the largest source of immigrants to the state, “immigrants from the North”

(the snowbelt states) constitute a much larger proportion of the state’s growing

population. Nonetheless, the delegates from the Miami area are considered a

powerful group in the legislature.

About 72 percent of the state’s general revenue ($15.6 billion in FY 96–97)

comes from sales tax collections.

2

The state does not have an income tax, and

only counties can impose ad valorem (property) taxes. For FY 97–98, the

Florida Consensus Estimating Conference projects the state’s general revenue

growth at 4.7 percent, or $757 million more in recurring general revenue, and

projects an overall revenue growth of 5 percent. This is down, however, from

the average annual rate of 8 percent in the last 10 years, when the introduction

of the Florida lottery and an infusion of federal funds because of rising

Medicaid and AFDC caseloads contributed to a higher growth rate.

Roadmap to the Rest of the Report

The remainder of this report lays out the major issues, initiatives, and chal-

lenges in health care facing the state policymakers in the spring of 1997. It

describes the state’s current health care agenda and recent spending trends,

describes the organizational structure of state health programs, and gives some

sense of prevailing state and local attitudes toward meeting the health care

needs of the poor. It then delves into the details of Medicaid eligibility, man-

aged care programs, provider reimbursement, and long-term care policy. The

report describes how state policies are affecting the health care delivery sys-

tem for poor people in two communities—Dade County, home to Miami, and

Hillsborough County, which includes Tampa. It concludes with a discussion

of the major challenges facing the state.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

8

Setting the Policy Context

Overview of the State’s Health Care Agenda

T

hree significant health care issues consumed the attention of state offi-

cials and advocates at the time of the site visit: (1) awards of new

Medicaid capitated managed care contracts and attempts to shift

MediPass program participants into capitated plans; (2) a number of

children’s health initiatives, including an expansion of the Healthy Kids

Program, which subsidizes insurance premiums for low-income, school-aged

children, and expansion of Medicaid eligibility to children ages 1 through 3 in

families earning up to 185 percent of the FPL; and (3) concerns about the impact

of federal welfare reform and immigration laws on Medicaid eligibility for legal

immigrants.

Florida’s Medicaid managed care program experienced significant problems

two years ago when contracting plans’ marketing abuses, quality of care prob-

lems, and charges of excess profit-taking were the focus of a series of articles

in the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel. The publicity led to several legislative

changes in 1995, including prohibitions on direct marketing, rate rollbacks of

between 8 and 18 percent, and the addition of Medicaid staff to monitor health

plans’ quality of care. In 1996, the legislature mandated assignment into either

MediPass, the primary care case management program, or a health maintenance

organization (HMO) or prepaid health plan (PHP) (previously recipients were

required to enroll only in MediPass). The legislature also mandated a competi-

tive bidding process for HMOs, setting a maximum capitation rate of 92 percent

of fee-for-service (FFS) rates, and it authorized more enrollee education regard-

ing managed care choices. Both the administration and the legislature have

focused on implementing these changes, addressing, in particular, problems

with the schedule and outcome of the bidding process.

In his FY 97–98 budget, the governor’s biggest priority was a set of chil-

dren’s initiatives that included 22 separate programs.

3

The most important was

the expansion of the Healthy Kids Program and Medicaid for young children,

consistent with the governor’s previous attempts to expand insurance coverage.

Despite his focus on children, who generally garner more support across the

aisle, the governor faced some roadblocks. Republican leaders in the legislature

expressed their strong opposition to creating any new “middle-class entitle-

ments,” and they seemed more interested in further Medicaid budget cuts than

in anything that would increase Medicaid spending.

Federal welfare reform legislation (the Personal Responsibility and Work

Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996—PRWORA) restricted immigrants’

eligibility for a wide range of benefits, including Medicaid. Prior to welfare

reform, legal noncitizens were eligible for Medicaid on the same basis as citi-

zens. The new law bars immigrants arriving after passage of the law (August 22,

1996) from receiving Medicaid for their first five years in the country. It also

gives states the option of providing Medicaid to immigrants already in the

United States.

At the time of the site visit, the state had made clear its intent to continue

Medicaid coverage for legal immigrants residing in the state who qualify for

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or AFDC/Temporary Assistance to Needy

Families (TANF) or who meet other Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Nonetheless, the state estimated that about 3,062 current Medicaid recipients

(not including SSI recipients) would likely be ineligible for Medicaid (66 per-

cent of whom reside in Dade County) under the federal welfare reform law, even

after accounting for those who would remain eligible because of exceptions,

naturalization, or state options. About 54,000 people would have lost SSI ben-

efits, with approximately 74 percent living in Dade County.

4

However, the pas-

sage of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 grandfathered SSI recipients present in

the United States as of August 22, 1996. As a result, most of the estimated

54,000 will not lose their benefits. Nonetheless, future immigrants will not be

covered by Medicaid for their first five years in the country, which will put pres-

sure on the state and local areas.

Observers were very concerned that many of those people who would have

lost coverage under the old rules would end up in nursing homes because they

could not afford rent or food to stay in the community. A legislative staffer

estimated that changes in Medicaid rules for legal immigrants before the enact-

ment of the Balanced Budget Act would have cost the state around $243 mil-

lion; if a quarter of the people losing SSI coverage moved into a nursing home,

state expenditures could have increased by about $432 million. Some believed

Miami nursing home representatives would successfully lobby the legislature

for such funds; others said it would depend on the state budget situation and

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

10

the way in which the media covered the issue. Similar uncertainties regarding

coverage of immigrants can be expected in the future under the new rules.

State Health and Health Care Indicators

Florida’s nonelderly uninsured rate of 19.2 percent is among the highest

state rates in the nation, exceeding the national average of 15.5 percent (table 1).

This may be attributable to the state’s service-dominated and small employer–

based economy. The rate has not decreased very much in the last few years,

despite the state’s overall strong economy. According to one source, Florida

ranks 38th lowest out of the 50 states with respect to an aggregation of health

indicators. Florida performs poorly on a number of health status measures: It

ranks in the bottom fifth of the country in the prevalence of infectious diseases,

motor vehicle deaths, and premature death rate and is ranked lowest (i.e.,

worst) with respect to the prevalence of cancer. The state has twice the rate of

AIDS cases as the national average and a 56 percent higher rate of violent crime.

Florida is closer to the U.S. average for such measures as low-birth-weight

births, infant mortality rates, and smoking among the adult population.

Health Care Spending and Coverage

Between FY 90–91 and FY 96–97, total average monthly caseloads under

the Medicaid program grew from 992,038 to 1,526,823—a 54 percent increase.

5

Most of the growth, however, occurred between FY 90–91 and FY 92–93,

because of recession-induced increases in AFDC caseloads and large increases

in the expanded eligibility groups—for instance, AFDC-Unemployed Parent

(UP), the medically needy program, poverty-related pregnant women and

infants (with income up to 185 percent of the FPL) and children, optional cov-

erage of elderly and disabled populations, and qualified Medicare beneficiaries.

Despite its eligibility expansions, Florida’s Medicaid program is still in the

bottom 10 states in percent of total low-income population covered.

The state has restricted benefits in order to limit acute and long-term care

costs; inpatient days are limited to 45, except for children, and the state does

not cover nursing home services for the medically needy. The state also does

not cover five optional services for the medically needy that it does cover for the

categorically needy: inpatient hospital services for persons over age 65 in insti-

tutions for mental disease, Intermediate Care Facility for the Developmentally

Disabled (ICF/DD) services, nursing facility services for individuals under age

21, case management services, and tuberculosis-related health services.

Florida’s Medicaid spending has increased as a share of all state expendi-

tures throughout the 1990s. Out of a total state 1995 budget of approximately

$35.9 billion, Medicaid’s share was $5.9 billion, or 16.5 percent, an increase

from 10.7 percent in 1990 (table 2). Medicaid’s share of state spending (exclud-

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

11

ing federal funds) also increased over this same period, from $812 million

(7.0 percent of state-only spending) to $1.9 billion (13.1 percent of state-only

spending). During the same period, state expenditures on elementary and sec-

ondary education and higher education fell as a share of all state expenditures.

Medicaid annual growth rates declined from over 20 percent in the late

1980s and early 1990s to an estimated 3.8 percent between FY 94–95 and FY

95–96, “due in large part to the economic recovery.”

6

During the next four years,

the average growth per year was estimated by administration officials to be

about 6.7 percent.

In 1995, state general revenues made up 70.5 percent of the nonfederal

share of Medicaid expenditures; the remainder came from a variety of sources,

primarily the Public Medical Assistance Trust Fund (PMATF) (17 percent of

the nonfederal share).

7

The PMATF was created in 1984 to provide an ongoing

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

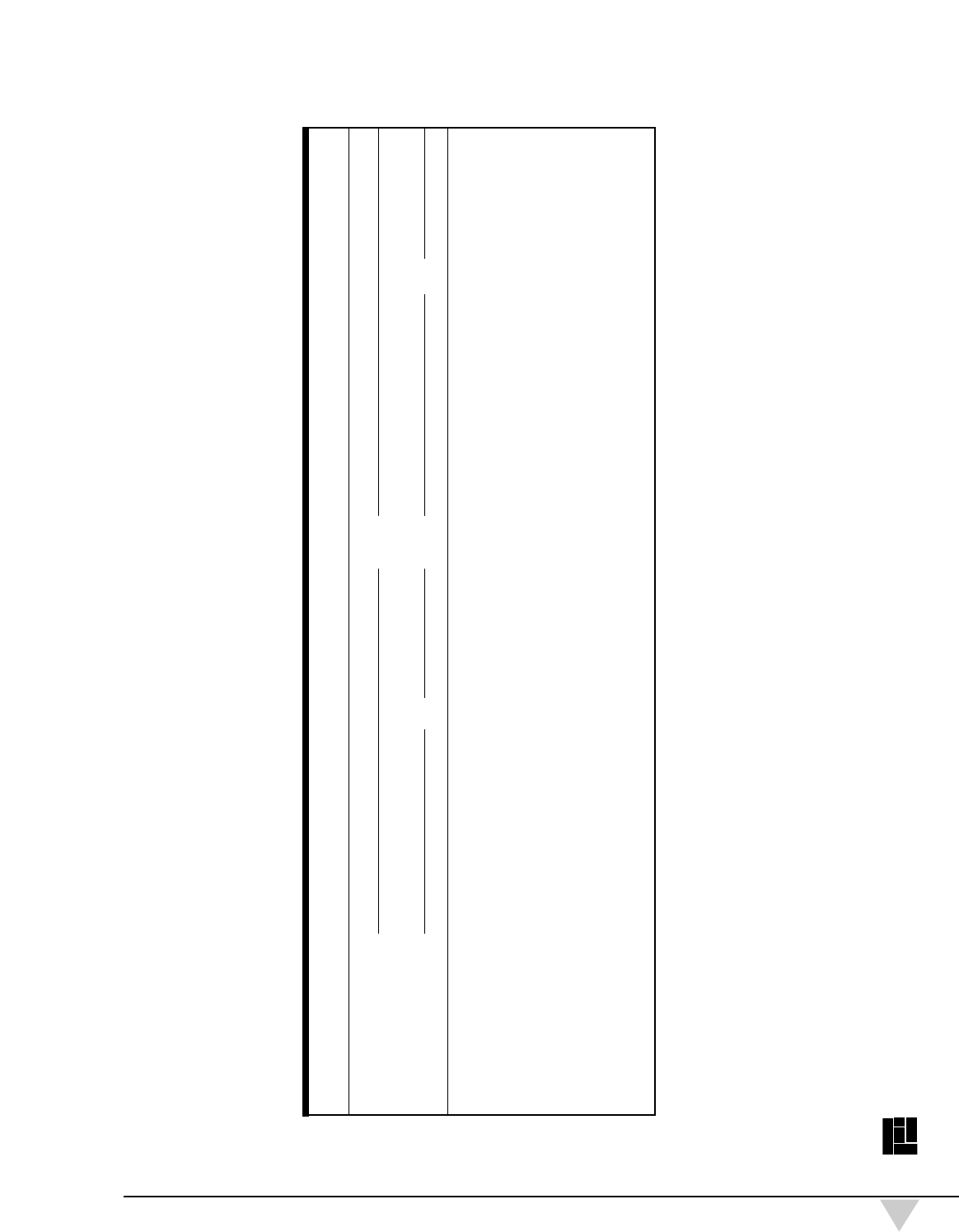

12

Table 2 Florida Spending by Category, 1990 and 1995 ($ in Millions)

State General-Fund Expenditures

a

Expenditures

b

Annual Annual

Program 1990 1995 Growth 1990 1995 Growth

Total $11,619 $14,649 4.7% $22,481 $35,907 9.8%

Medicaid

c, d

812 1,921 18.8 2,407 5,931 19.8

% of Total (7.0 ) (13.1 ) — (10.7 ) (16.5 ) —

Corrections 709 1,398 14.5 864 1,472 11.2

% of Total (6.1 ) (9.5 ) — (3.8 ) (4.1 ) —

K–12 Education 5,808 5,907 0.3 6,431 6,715 0.9

% of Total (50.0 ) (40.3 ) — (28.6 ) (18.7 ) —

AFDC 162 312 14.0 403 782 14.2

% of Total (1.4 ) (2.1 ) — (1.8 ) (2.2 ) —

Higher Education 1,536 1,663 1.6 2,321 1,999 (2.9)

% of Total (13.2 ) (11.4 ) — (10.3 ) (5.6 ) —

Miscellaneous

e

2,592 3,448 5.9 10,055 19,008 13.6

% of Total (22.3 ) (23.5 ) — (44.7 ) (52.9 ) —

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, 1992 State Expenditure Report (April 1993) and 1996 State Expenditure

Report (April 1997).

a. State spending refers to general-fund expenditures plus other state fund spending for K–12 education.

b. Total spending for each category includes the general fund, other state funds, and federal aid.

c. States are requested by the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) to exclude provider taxes, donations, fees, and

assessments from state spending. NASBO asks states to report these separately as “other state funds.” In some cases, however, a

portion of these taxes, fees, etc., is included in state spending because states cannot separate them. Florida reported other state funds

of $237 million in 1990 and $659 million in 1995.

d. Total Medicaid spending will differ from data reported on the HCFA 64 for three reasons: first, NASBO reports on the state fis-

cal year and the HCFA 64 on the federal fiscal year; second, states often report some expenditures, (e.g. mental health and/or mental

retardation) as “other health” rather than Medicaid; third, local contributions to Medicaid are not included, but would be part of

Medicaid spending on the HCFA 64.

e. This category includes all remaining state expenditures (e.g., environmental projects, transportation, housing, and other cash-

assistance programs) not captured in the five listed categories.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

13

Table 3 Medicaid Expenditures by Eligibility Group and Type of Service, Florida and United States (Expenditures in Millions)

Florida United States

Average Annual Average Annual

Expenditures Growth Expenditures Growth

1990 1992 1995 1990–92 1992–95 1990 1992 1995 1990–92 1992–95

Total $2,657.4 $4,298.1 $6,274.7 27.2% 13.4% $73,662.2 $118,926.0 $157,872.5 27.1% 9.9%

Benefits

Benefits by Service $2,490.5 $3,958.1 $5,799.9 26.1% 13.6% $69,168.7 $97,602.4 $133,434.6 18.8% 11.0%

Acute Care 1,626.2 2,784.7 4,030.7 30.9% 13.1% 36,904.5 55,059.9 79,438.5 22.1% 13.0%

Long-Term Care 864.4 1,173.4 1,769.3 16.5% 14.7% 32,264.2 42,542.5 53,996.1 14.8% 8.3%

Benefits by Group $2,490.5 $3,958.1 $5,799.9 26.1% 13.6% $69,168.7 $97,602.4 $133,434.6 18.8% 11.0%

Elderly $887.0 $1,229.4 $1,755.0 17.7% 12.6% $23,334.3 $31,757.9 $40,087.4 16.7% 8.1%

Acute Care 307.8 432.5 637.5 18.5% 13.8% 4,925.4 6,911.5 9,673.7 18.5% 11.9%

Long-Term Care 579.2 796.9 1,117.5 17.3% 11.9% 18,408.9 24,846.4 30,413.7 16.2% 7.0%

Blind & Disabled $779.3 $1,272.4 $1,908.6 27.8% 14.5% $25,771.6 $35,684.6 $51,379.4 17.7% 12.9%

Acute Care 497.1 908.7 1,276.1 35.2% 12.0% 12,929.2 19,483.6 29,760.7 22.8% 15.2%

Long-Term Care 282.2 363.8 632.5 13.5% 20.3% 12,842.4 16,201.0 21,618.7 12.3% 10.1%

Adults $370.3 $436.5 $505.9 8.6% 5.0% $8,765.0 $12,710.1 $16,556.9 20.4% 9.2%

Children $453.9 $1,019.8 $1,630.5 49.9% 16.9% $11,297.8 $17,449.8 $25,410.9 24.3% 13.3%

DSH $44.3 $191.4 $334.2 107.9% 20.4% $1,340.9 $17,525.6 $18,988.4 261.5% 2.7%

Administration $122.6 $148.5 $140.6 10.1% –1.8% $3,152.6 $3,797.9 $5,449.4 9.8% 12.8%

Source: The Urban Institute, 1997. Based on HCFA 2082 and HCFA 64 data.

funding source for indigent health care programs. It raises funds from a

1.5 percent assessment on each hospital’s net operating revenue and from

other selected health care providers, in addition to a portion of the cigarette

tax. PMATF funds have been used to finance Medicaid eligibility expansions,

disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and county primary care

programs.

Increases in Florida’s Medicaid expenditures, both federal and state, in the

early 1990s were similar to those at the national level—27 percent average

annual growth rates between 1990 and 1992 (table 3). These increases were

caused largely by growth in AFDC and Medicaid enrollment, in part due to the

economic recession of the early 1990s, and by the expansion of Medicaid eligi-

bility to additional groups. Average annual growth rates in the state’s Medicaid

spending between 1992 and 1995 dropped significantly—to 13.4 percent on

average—but were still in excess of the national average of 9.9 percent during

that period. This higher-than-average spending was primarily due to much

greater spending increases in long-term care, primarily for the elderly. As a

percent of total 1995 expenditures, Florida spent more on acute care than the

national average (64 percent versus 50 percent), less on long-term care (28 per-

cent versus 34 percent), and less than half as much on DSH payments—5 per-

cent versus 12 percent.

The average growth in Medicaid expenditures per beneficiary in Florida

from 1992 to 1995 was 7.0 percent versus 5.5 percent for the United States as a

whole, and the excess rate of growth appeared to be concentrated on the elderly

and children (table 4). Nonetheless, the level of Medicaid expenditures per

enrollee was 16.1 percent below the national average in 1995. Largely because

of low levels of long-term care spending, expenditures per enrollee for the

elderly and disabled were 20.0 percent and 28.1 percent below the national

average, respectively. Average expenditures per child enrollee were 15.4 per-

cent above the national average.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

14

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

15

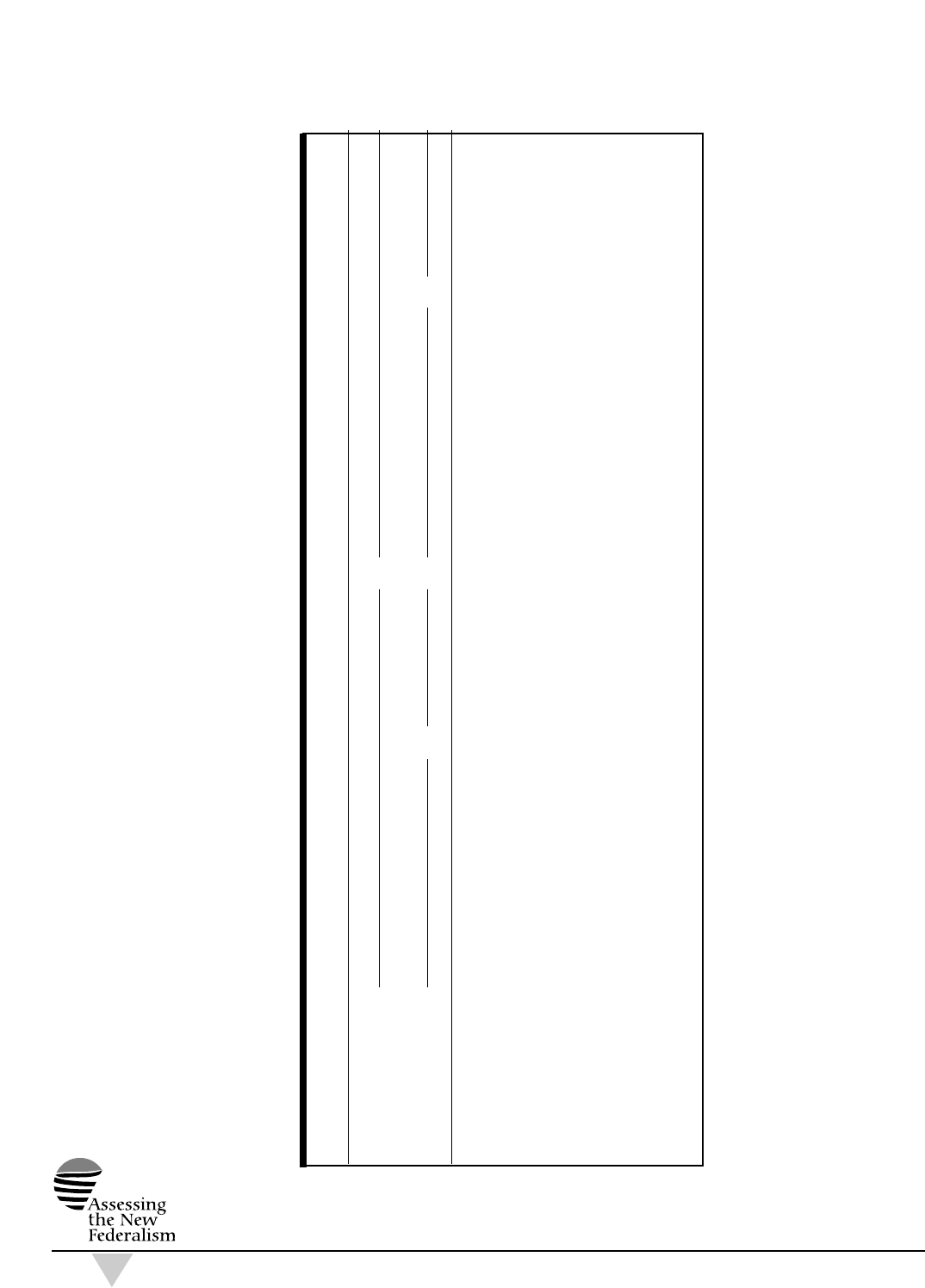

Table 4 Medicaid Expenditures per Enrollee by Eligibility Group, Florida and United States

Florida United States

Spending per Average Annual Spending per Average Annual

Enrollee Growth Enrollee Growth

1990 1992 1995 1990–92 1992–95 1990 1992 1995 1990–92 1992–95

Total $2,099 $2,195 $2,686 2.2% 7.0% $2,397 $2,729 $3,202 6.7% 5.5%

By Group

Elderly $5,300 $6,277 $7,793 8.8% 7.5% $6,839 $8,422 $9,738 11.0% 5.0%

Cash 3,086 3,175 3,585 1.4% 4.1% 3,329 4,017 4,818 9.8% 6.2%

Noncash 8,061 9,612 11,902 9.2% 7.4% 10,377 12,192 13,521 8.4% 3.5%

Blind and Disabled $4,251 $5,475 $5,767 13.5% 1.8% $6,378 $7,320 $8,022 7.1% 3.1%

Cash 3,785 5,060 5,535 15.6% 3.0% 4,969 5,927 6,686 9.2% 4.1%

Noncash 7,765 7,820 6,801 0.3% –4.5% 12,047 12,574 12,660 2.2% 0.2%

Adults $1,417 $1,252 $1,250 –6.0% 0.0% $1,301 $1,518 $1,728 8.0% 4.4%

Children $790 $993 $1,360 12.1% 11.0% $770 $931 $1,178 9.9% 8.2%

Source: The Urban Institute, 1997. Based on HCFA 2082 and HCFA 64 data.

Organizational Structure of

State Health Programs

T

he state has undergone several reorganizations of its health and human

services programs during this decade. Prior to 1992, the Department

of Health and Rehabilitative Services (DHRS) housed all health pro-

grams, including Medicaid, public health, and mental health, as well

as welfare and a range of other social service programs. In the Health Care

Reform Act of 1992, the state removed Medicaid from this enormous umbrella

department and placed it in the newly created Agency for Health Care

Administration, which reports to the governor. AHCA also has authority over

a number of health regulatory functions, including hospital budget review,

licensing and regulation of health facilities (including certificate of need), and

health care–related professional licensure. Furthermore, it oversees health care

purchasing for state employees and the newly created CHPAs for small firms

and self-employed individuals seeking coverage. DHRS retained authority over

public health and mental health in addition to other health-related programs

such as Children’s Medical Services, which operates clinics and coordinates

services for 80,000 children with disabilities throughout the state.

8

By 1996, the arrangement of health and social services was once more found

to be unsatisfactory. DHRS was still an immense human services bureaucracy,

and many believed that public health was being shortchanged. Thus, the state

created a separate Department of Health, which was given responsibility for the

divisions of family health, environmental health, and disease control, as well as

Children’s Medical Services from the former DHRS. At the same time, DHRS

was given a new name: the Department of Children and Family Services. It

still has control over Medicaid eligibility rules, as well as the mental health,

substance abuse, and developmental disability programs.

Florida’s 67 counties are responsible for administering health services pro-

grams. Each county operates a county public health unit, which is an adminis-

trative and delivery unit of the state Department of Health. While local health

department directors report to the county commissioners, county health depart-

ments are essentially state franchises; in fact, all staff are employed by the state.

Nonetheless, decisions regarding the types of services to be provided and how

to provide them are determined by each county public health unit. Nearly all of

the state’s 67 counties supplement the funds received from the state to support

their county public health department, though the amount varies tremendously

by county. Counties also share in the financing of Medicaid; they pay $55 per

month for each nursing home resident and 35 percent of the nonfederal share

for inpatient days 13 through 45.

9

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

18

Assessing the New Federalism:

Potential State Responses

to Additional Flexibility

and Reduced Funding

General State Philosophy toward the Poor

G

overnor Chiles has made a concerted effort to expand health insurance

coverage for low-income people. But in a state that has built-in limits

on tax revenues, a tax expenditure cap, and a fiscally conservative leg-

islature, he has had to settle for less than his ambitions. The legislative

agenda in 1996 was dominated by a debate over funding priorities, which was

cast as a trade-off between social and health services on the one hand and edu-

cation and corrections on the other. As in the previous year, the legislature

explicitly took funds proposed for Medicaid and transferred them to corrections

and education. There is concern in the legislature over Medicaid spending

growth and its impact on expenditures for education, job creation, economic

development, and criminal justice. In recent years, policymakers have resisted

expanding entitlements and have made regular attempts to constrain growth

in the Medicaid program. Perhaps because Medicaid eligibility and benefits

are lower than the national average, there has been little concern about attract-

ing out-of-state low-income residents.

It was surprising not to find greater support for long-term care spending,

which seems inconsistent with the large number of elderly who make up the

state’s electorate. Interviewees attributed this apparent contradiction to the fact

that many elderly have higher incomes or assets that shield them from reliance

on publicly supported services. The predominance of Latinos, whose culture

expects families to take care of their elderly parents, may also be a factor.

Medicaid-Specific Issues

According to a spokesperson for the governor, the per capita Medicaid

spending cap proposed by President Clinton earlier in 1997 would be accept-

able if it gave the state some additional flexibility to run its Medicaid program.

In particular, the state would like to be less subject to the federal courts, which

are “acting as legislators.” The spokesperson also indicated that the state has

applied for a number of waivers, some of which have been under considera-

tion by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) for a long time. If

the state had not had to obtain approval for these waivers, it might have been

able to implement some innovative and potentially cost-saving programs more

quickly.

Some sources said the state wanted to have the Boren amendment

10

repealed, as some of the Boren-related suits have forced the state to pay more

than it would have liked on a number of occasions. Others agreed that a repeal

of the Boren amendment would help the state most by relieving it from having

to fight provider lawsuits, though rates would probably not change significantly.

Florida has not been as aggressive as some other states in maximizing fed-

eral funds. The state has not “abused” provider taxes and DSH spending as

much as other states have done, according to many sources. However, the state

continues to lobby extensively at the federal level to ensure “that Florida

receives a more equitable share of available federal assistance.”

11

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

20

Providing Health Coverage for

Low-Income People

Medicaid Eligibility

F

lorida is less generous in its eligibility standards for Medicaid than the

average state; in 1994, 39.6 percent of the low-income population below

150 percent of the FPL had Medicaid coverage, compared with 51 per-

cent nationally.

12

Under Florida’s Medicaid program, families with chil-

dren receiving AFDC, intact families with children, and families with unem-

ployed parents are eligible for coverage if their family income is below 28

percent of the FPL; the national average for eligibility is 41.9 percent of the FPL.

Florida has taken advantage of the option to cover pregnant women and infants

up to 185 percent of the FPL, and it has a medically needy program that covers

individuals whose medical expenses bring their income down to 28 percent of

the FPL (though the state could have extended this to 37 percent of the FPL

but did not). In addition, Florida Medicaid covers aged and disabled individu-

als with incomes up to 90 percent of the FPL and has an institutional care pro-

gram that provides nursing home and ICF/DD services to individuals with

incomes up to 300 percent of the SSI standard.

Table 5 shows that Medicaid enrollment increased from 1.2 million in 1990

to 1.8 million in 1992 (a 23.3 percent increase per year) and to 2.2 million by

1995 (another 6.2 percent increase per year). Increases in Medicaid-AFDC

enrollment averaged 24.9 percent per year between 1990 and 1992; it slowed

dramatically thereafter, averaging only 2.9 percent per year between 1992 and

1995. Medicaid-SSI enrollment grew by 8.4 percent per year from 1990 through

1995. By far the greatest increases in enrollment occurred as a result of

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

22

Table 5 Medicaid Enrollment by Eligibility Group, Florida and United States (Enrollment in Thousands)

Florida United States

Average Annual Average Annual

Enrollment Growth Enrollment Growth

1990 1992 1995 1990–92 1992–95 1990 1992 1995 1990–92 1992–95

Total 1,186.3 1,803.4 2,159.3 23.3% 6.2% 28,856.7 35,765.1 41,672.0 11.3% 5.2%

By Group

Elderly 167.4 195.9 225.2 8.2% 4.8% 3,412.2 3,771.0 4,116.6 5.1% 3.0%

Cash 92.9 101.5 111.3 4.5% 3.1% 1,713.1 1,739.2 1,789.2 0.8% 1.0%

Noncash 74.5 94.4 113.9 12.6% 6.5% 1,699.1 2,031.8 2,327.3 9.4% 4.6%

Blind and Disabled 183.3 232.4 330.9 12.6% 12.5% 4,040.9 4,875.1 6,405.2 9.8% 9.5%

Cash 161.9 197.5 270.2 10.5% 11.0% 3,236.8 3,853.4 4,973.5 9.1% 8.9%

Noncash 21.4 34.9 60.8 27.6% 20.3% 804.1 1,021.7 1,431.7 12.7% 11.9%

Adults 261.3 348.6 404.6 15.5% 5.1% 6,738.7 8,373.3 9,584.2 11.5% 4.6%

Cash 159.0 237.4 278.3 22.2% 5.4% 4,651.6 5,342.5 5,441.4 7.2% 0.6%

Noncash 102.3 111.2 126.2 4.2% 4.3% 2,087.2 3,030.9 4,142.8 20.5% 11.0%

Children 574.3 1,026.5 1,198.6 33.7% 5.3% 14,664.9 18,745.7 21,566.0 13.1% 4.8%

Cash 381.7 606.7 641.9 26.1% 1.9% 9,946.2 11,281.8 11,314.6 6.5% 0.1%

Noncash 192.6 419.8 556.7 47.6% 9.9% 4,718.7 7,463.9 10,251.4 25.8% 11.2%

Source: The Urban Institute, 1997. Based on HCFA 2082 data.

expanded eligibility groups—AFDC-UP, the medically needy program, poverty-

related pregnant women and infants (up to 185 percent of the FPL) and chil-

dren, optional coverage of elderly and disabled populations, qualified Medicare

beneficiaries, and specified low-income Medicare beneficiaries, which com-

bined to account for 44 percent of the increase in the total Medicaid caseload.

Among these groups, the largest increase, both in percentage terms and actual

numbers, was for poverty-related children. State data indicate that average

monthly caseloads for this group grew from 65,277 in FY 90–91 to 220,918 in

FY 96–97—an increase of 238 percent, accounting for more than 58 percent of

the growth in expanded eligibility groups.

13

The improved economy appears to have contributed to declines in average

monthly caseloads over the past three years. Average monthly Medicaid cases

dropped from a high of 1.6 million in FY 93–94 to 1.5 million in FY 96–97.

The improved economy has also been reflected in declines in Medicaid-

related AFDC caseloads, which went from a high of 832,942 people in

FY 93–94 to 738,955 in FY 95–96, and was projected to fall below 650,000

in FY 97–98.

The state received approval of its Section 1115 waiver application in 1994.

That program, had the legislature authorized it, would have subsidized private

health insurance to uninsured people earning up to 250 percent of the FPL who

were without coverage for the previous 12 months or had just left Medicaid.

Health insurance would have been available through the CHPAs. The state pro-

posed to finance this expansion in eligibility through savings from enrolling

more people in Medicaid managed care plans and from phasing out the med-

ically needy program, decreasing institutional provider rates, and reducing

DSH payments. An estimated 1.1 million persons could have enrolled, accord-

ing to projections. One of the major objections to the program in the Senate

(the bill was passed by the House but not the Senate) was that the income level

was too high, leading to “middle class welfare.”

14

The state’s welfare reform program is called WAGES (Work and Gain

Economic Self-sufficiency). It builds on the previous Family Transition Program

(FTP), which began in 1993 as a two-county pilot project in Alachua and

Escambia Counties. Under the pilot project, most AFDC recipients had a two-

year time limit for cash assistance and were allowed to keep more of their earn-

ings in order to create savings accounts. The project also broadened eligibility

in JOBS (Job Opportunity and Basic Skills) participation, and offered case man-

agement support to families.

Consensus that FTP’s approach was the right direction for the state resulted

in 1996 legislation authorizing WAGES. WAGES put stricter limits on the time

recipients were allowed to receive cash assistance. It also placed a 48-month

lifetime limit on benefits, required adults to work or engage in work-related

activities as a condition of receiving benefits, established immediate sanctions

for people who do not comply with work requirements, and required teen par-

ents to live at home under adult supervision and stay in school.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

23

The Department of Children and Family Services is responsible for recom-

mending policies related to Medicaid under the federal welfare reform law. The

state has an integrated eligibility system to assure that all TANF recipients will

be enrolled in Medicaid. Several interviewees believed that the biggest chal-

lenge for welfare reform would be a national economic recession: They thought

that Florida would then be more seriously affected because during economic

hardship, people who are unemployed often move from cold areas to places

like Florida, where it can be cheaper to live. At the same time, few in the state

were worried about state welfare benefits serving as an attraction to those from

out of state; these benefits are already near the bottom relative to other states

and are expected to remain there.

Other Public Financing Programs

Florida does not have a statewide General Assistance program, and thus it

has no General Assistance medical program either. Only one state program

other than Medicaid provides assistance to low-income, otherwise uninsured

people—the Healthy Kids Program.

The Healthy Kids Program is a school enrollment–based insurance pro-

gram that provides comprehensive health insurance coverage to approximately

39,300 school-aged children and their younger siblings as of August 1997.

15

The

program has won national awards for innovation in government, and the Robert

Wood Johnson Foundation has recently committed a significant amount of

funds to help other states replicate the program. It began in 1991 as a three-

year Medicaid Section 1115 waiver demonstration, financed with state and

federal funds. When the demonstration ended, federal financing also stopped;

as of FY 96–97, the program relies on financing from the state (about 49 per-

cent), participating families (about 35 percent), and local governments (about

16 percent).

16

As of this writing, the Healthy Kids Program is operating in 17 counties

throughout the state (an increase from 9 counties in the previous year), covering

approximately half of the uninsured children in the state.

17

To participate, local

school districts, which in Florida correspond to counties, must contribute an

increasing share of total program costs over time, usually obtained from ad

valorem taxes.

All school-aged children and their younger siblings are eligible for the

Healthy Kids Program. Of participating children, 71 percent come from house-

holds with incomes below 133 percent of the FPL; 15 percent, from house-

holds with incomes between 134 and 185 percent of the FPL; and 14 percent,

from households with incomes above 185 percent of the FPL. The Healthy Kids

Program encourages parental responsibility by requiring families to contribute

to the costs of providing health insurance for their children. Each local area

develops a sliding-scale premium schedule, with eligibility for reduced premi-

ums tied to eligibility for the free- and reduced-lunch programs. There are also

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

24

copayments for some services. The average monthly cost of the Healthy Kids

Program is $51.00. Participating health plans are selected based on competi-

tive bids, and only one health plan is chosen in each county.

In 1996, Governor Chiles requested $36 million for Healthy Kids from the

legislature and received $13 million to expand the program. In 1997, he

requested and received an additional $16 million, which will expand the pro-

gram to serve a total of 60,000 children. (This averages $450 per child, less

than the average cost of the program because of (1) local government and family

contributors and (2) differences in the expected costs of the new target popula-

tion.) In addition, the legislature granted ACHA the authority to seek a Section

1115 waiver to cover children with incomes up to 185 percent of the FPL

through the Healthy Kids Program. According to Healthy Kids officials, if this

waiver is approved, it would allow the program to cover 118,000 children and

thus 15.7 percent of the state’s estimated 750,000 uninsured children.

Insurance Reforms

Florida’s health insurance reforms were enacted as part of the 1992 and

1993 health care reform laws. Both laws regarded reform of small-group health

insurance as an important component of promoting competition in health care

and using managed care to achieve cost savings. The 1992 law defined small

groups as including 50 employees or less, and all insurers offering policies to

small groups were mandated to offer basic and standard benefit plans defined

by the Department of Insurance. The 1993 law required all insurers offering

policies to small groups to guarantee issue of policies without regard to health

status, preexisting conditions, or claims history; provided portability of plans

between employers; and required the use of modified rating on all small-group

products, with adjustments allowed for age, gender, family composition,

tobacco usage, and geographic location. Neither law affected the individual

market.

Since 1993, there has been no legislative action with respect to insurance

reform in the small-group or individual market. At the time of the site visit,

Florida legislative staff were working to implement an alternative mechanism

for the individual insurance market portability reforms to meet federal provi-

sions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. According to

respondents, the state had two options: (1) Mandate that group or individual

carriers offer coverage, or (2) Reopen the state’s high-risk pool.

18

Group insur-

ance carriers were prodding individual market carriers to offer some products,

while individual carriers were trying to convince the state to reopen its high-

risk pool.

As part of its “managed-competition” health care reform laws, Florida cre-

ated 11 regional Community Health Purchasing Alliances in 1993 as state-char-

tered, nonprofit private purchasing organizations. CHPA membership is avail-

able to, though not mandated for, firms that have 50 or fewer full-time

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

THE URBAN

INSTITUTE

25

employees, including the self-employed. All policies provided through the

CHPAs must be issued through an insurance agent. In 1995, there were 64 reg-

istered carriers in the small-group market.

19

Forty are designated as

Accountable Health Plans (AHPs), which are allowed to offer HMO, preferred

provider organization (PPO), point-of-service (POS), and extended provider

organization (EPO) products through the CHPAs. Since the inception of CHPAs,

there has been significant growth in the number of individuals covered; by

January 1997, 18,000 small businesses were participating, representing more

than 76,000 covered lives.

20

Though the program does not directly subsidize

insurance premiums, slightly less than half of the 76,000 enrollees were previ-

ously uninsured. This proportion is higher than that in other states’ purchas-

ing cooperatives for small businesses—almost double that in the Health

Insurance Plan of California, for example—because Florida allows groups of

one (the self-employed) to enroll.

Despite the potential of CHPAs to lower uninsurance rates among small

firms, several factors limit their ability to provide more affordable insurance.

According to the Florida Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government

Accountability (OPPAGA), CHPAs may suffer from adverse selection; that is,

those who need insurance because they have medical conditions are more

likely to purchase it.

21

The majority of enrolled firms had only one to two

employees, whereas only 1 percent had 20 to 50 employees. This suggests a

fair amount of adverse selection, leading insurers to charge higher premiums. In

addition, CHPAs are prohibited from negotiating rates with insurers so that the

CHPAs cannot take advantage of their market power. Because of these factors,

premiums for CHPA-sponsored insurance plans were only about 6 percent less

than premiums for the same plans offered outside of the CHPAs, according to a

1995 report commissioned by OPPAGA. This is less than the cost advantage

expected for group purchasing.

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

26

Financing and Delivery System

F

lorida’s health care market is one of the most competitive and entre-

preneurial in the country. Most HMOs are for-profit and are in a period

of instability; mergers and acquisitions are occurring at a fast pace. In

addition, more hospitals are for-profit than in most other states. There

has been little apparent public concern over issues raised by conversions from

nonprofit to for-profit status. However, the recent emergence of alliances

between public hospitals and investor-owned organizations and the potential

conversion of some of the bigger public hospitals to private ownership (such

as Tampa General) are likely to increase interest in this issue.

Hospitals, and in particular hospitals in the larger systems, are faring rela-

tively well, perhaps because of the large Medicare market. (Medicare is gener-

ally seen as a better payer than private managed care plans.) The hospital indus-

try remains over-bedded, which means that HMOs can still negotiate significant

discounts. Safety net institutions are in relatively good financial health, in large

part because of local financing arrangements that exist in many of the metro-

politan areas with large low-income populations.

Commercial Managed Care

Commercial managed care has been growing rapidly in Florida, as more

purchasers of health care switch to managed care as a lower cost insurance

alternative. As of 1995, 25 percent of the state’s population was enrolled in an

HMO.

22

HMO market penetration, however, varies considerably across the state.

Tallahassee, dominated by state employees who have incentives to enroll in

managed care plans, has the highest HMO penetration, at 42.1 percent. Dade

County has the second highest, at 40.8 percent, and the Tampa–St. Petersburg

area has approximately 28.1 percent HMO penetration. As of 1992, 26.7 percent

of the state’s population was enrolled in a PPO.

Enrollment in commercial managed care is concentrated in a few HMOs. As

of 1996, 10 HMOs accounted for approximately 81 percent of commercial

enrollment, and 5 HMOs (Blue Cross/Blue Shield’s [BC/BS] Health Options,

Humana Medical Plan, United Health Care Plans of Florida, Prudential Health

Care Plan, and Cigna) accounted for almost 60 percent of the market.

The Florida HMO market has been a profitable one, but it has become less so

in the last few years, particularly for the smaller HMOs. In 1995, with a few

exceptions, the top 10 HMOs fared quite well, recording net revenues in excess

of $125 million, or 86 percent of total HMO profits.

23

The remaining 28 HMOs,

with approximately 20 percent of the market, garnered only 14 percent of the

profits. More recent data show that about half of the state’s HMOs had losses

in the last quarter of 1996. Medicaid HMOs showed particular signs of financial

distress as state rate reductions and increasing competition have made their

margins much smaller. Consolidation in the market is expected, as smaller,

struggling HMOs are attractive acquisitions for larger Florida-based and

national HMOs.

In the last decade, state policy has generally favored the growth of man-

aged care. Yet, as in the rest of the country, the last two years have seen a spate

of new legislation to regulate managed care. In 1996, the state enacted Senate

Bill (SB) 886, which included a number of changes to state regulations of man-

aged care organizations. First, the bill required the Department of Insurance to

publish the medical loss ratios of all plans, although there continues to be

debate around how to categorize certain expenses (medical expense vs. admin-

istration and profit). SB 886 also required HMOs to pay for emergency room

screening tests that are consistent with symptoms. The law further required a

minimum length of stay for maternity cases.

At the time of our visit, the 1997 legislative session appeared likely to see

another round of legislation. According to the Florida Association of HMOs

(FAHMO)

24

and state legislative staff, likely bills included greater access to

certain specialists; prohibitions on gag clauses (though most HMOs have

already adopted the “patient rights” principles of the American Association of

Health Plans); requirements that HMO medical directors be licensed in Florida;

written standards on referrals, quality, and access indicators; uniform cus-

tomer satisfaction surveys; establishment of an early and periodic screening,

diagnosis, and treatment (EPSDT) target of 90 percent versus the current rate

of 60 percent for Medicaid HMOs; expedited grievance procedures; medical

necessity processes; provider credentialing requirements; and ownership of

patients’ medical records by physicians.

25

None were considered by FAHMO

to be worth a serious fight, given the negative publicity that HMOs have been

receiving. There have been concerns about HMO quality, especially among

Medicaid HMOs. (These issues are discussed below in the Medicaid managed

care section.)

HEALTH POLICY FOR LOW-INCOME PEOPLE IN FLORIDA

28

Hospital Market and Regulatory Issues

The Florida hospital market is considered over-bedded. As of 1996, hospi-

tals averaged only a 51 percent occupancy rate.

26

The competitive pressures

exerted on hospitals by HMOs and other managed care plans through negoti-

ated discounts have forced hospitals to change rapidly. Their responses have

included consolidating through acquisitions and mergers to attain greater effi-

ciencies and market leverage, aligning with physicians either in physician-

hospital organizations that can contract with managed care plans or buying

physician practices outright, developing or becoming part-owner in an HMO,

and attempting to convert acute care beds to subacute or nursing-care beds.

It is in this last area that state policy has been most influential. The state’s

certificate-of-need program—which attempts to maintain nursing home occu-

pancy rates at 91 percent—makes redeploying excess acute beds to nursing-care

beds difficult. The nursing home industry has fought the hospital association’s

attempt to deregulate conversion of beds from acute to subacute, leading to

legislative defeats for hospitals in both 1995 and 1996. Both sides agreed that

it could once more become a legislative issue in 1997.

Mergers and For-Profit Conversions

Reflecting trends in the rest of the country, Florida HMOs are consolidat-

ing through acquisitions and mergers. In total, there were 18 mergers or acqui-

sitions between 1993 and 1996.

27

Most of the big HMOs in Florida are mem-

bers of national chains. Hospitals also have been consolidating, and in the

process, the hospital market in Florida has changed from one of independent

hospitals to one dominated by several large hospital systems. According to the

Florida Hospital Association, 77 transactions have occurred involving an acqui-

sition or merger of a hospital or group of hospitals since 1990, peaking in 1994.

By 1996, 76 percent of the beds and hospitals were in a hospital system. The

resultant market is dominated by three hospital systems, Columbia/HCA, Tenet

HealthCare, and Adventist Health System/Sunbelt, which together account for

45 percent of the hospitals and beds in the state. While for-profit systems have

been driving the consolidation movement, nonprofit systems are growing as

well. Although consolidation activities have been high, the actual impact on the

number of hospitals and beds has been relatively small. Between 1990 and

1995, a net reduction of only 213 acute-care hospital beds occurred.

An interesting development in Florida has been the discussion or formation

of joint ventures and coalitions between public and for-profit institutions.

Public hospitals in both Jacksonville and Miami have proposed or discussed a

joint venture with Columbia/HCA. The University Medical Center in Jackson-

ville has planned to enter into an operating agreement with for-profit Columbia/