March 2018

This report was prepared by the

Trust for America’s Health, with funding from

The John A. Harord Foundaon

Challenges, Opportunities,

and

Next Steps

Creating an Age-Friendly

Public Health System

P a g e 1 | 18

Creating an Age-Friendly Public Health System:

Challenges, Opportunities, and Next Steps

Amanda J. Lehning and Anne De Biasi

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 2

Aging and Public Health 3

Demographic Changes and an Aging Society 4

Challenges and Opportunities of an Aging Society 5

An Age-Friendly Paradigm Shift 6

A Framework for an Age-Friendly Public Health System 7

Barriers to C reating an Age-Friendly Public Health System 11

Next Steps 12

Participant List 14

Endnotes 16

Amanda J. Lehning is an assistant professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore School of Social Work and a former

Health and Aging Policy Fellow with the Office of the Surge on General. Her research focuses on progra ms, polic ie s, and

neighborhood infrastructure that pr omote the optimal health, well-being, and ability to age in place of older adults.

Anne De Biasi is director of policy develop ment at the Trust for America’s Health (TFAH). She is responsible for defining

the agenda and strategy associated with TFAH’s goal to create a modernized, acco untable public health system and to

integrate preventio

n into a re forming health care system.

Trust for America’s Health is a nonprofit, nonpartisan o rganization d edicated to saving lives by protecting the health of every

community and working to make disease prevention a national priority.

The John A. Hartford Foundation is a national philanthropy dedicated to improving the care of older ad ults.

The Milbank Memorial Fund is a n e ndowed operating foundation that works to improve the health of populations by

connecting leaders and decision makers with the best available evidence and experience

.

Page 2 | 18

Executive Summary

Trust for America’s Health (TFAH), funded by The John A. Hartford Foundation, held a convening

called A Public Health Framework to Support the Improvement of the Health and Well-being of Older

Adults, in Tampa, Florida on October 27, 2017. National, state, and local public health officials; aging

experts, advocates, and service providers; and health care officials came together to discuss how public

health could contribute to an age-friendly society and improve the health and well-being of older

Americans. The goal of the convening was to develop a public health framework to support the

improvement of the health and well-being of older adults, focusing on areas where public health can

support, complement, or enhance aging services. Secondary goals included learning from the innovative

aging work in Florida and building rapport between the public health and aging sectors.

Participants strongly endorsed a greater role for public health in supporting the improved health and

well-being of older adults. The convening process began with presentations and discussions designed to

build a shared understanding of the strengths and challenges of both the aging services and public health

sectors. Through an examination of case studies of older adults, participants identified gaps in services,

supports, and policies needed to improve the health and well-being of older adults, and considered the

potential roles public health could play in filling these identified gaps. The convening resulted in a

preliminary Framework for an Age-Friendly Public Health System, described below, that outlines the

functions that public health could fulfill, in collaboration with aging services, to address the challenges

and opportunities of an aging society. The main takeaway from the convening was the need for an age-

friendly public health system that recognizes aging as a core public health issue.

For the purposes of the convening and this summary report, supporting healthy aging is defined as

comprising three key components: 1) promoting health, preventing injury, and managing chronic

conditions; 2) optimizing physical, cognitive, and mental health; and 3) facilitating social engagement.

i

This definition intentionally does not equate healthy aging with the absence of disease and disability.

Instead, it portrays healthy aging as both an adaptive process in response to the challenges that can occur

as we age and a proactive process to reduce the likelihood, intensity, or impact of future challenges.

Healthy aging involves maximizing physical, mental, emotional, and social well-being, while

recognizing that aging often is accompanied by chronic illnesses and functional limitations, including

lifelong conditions. And it emphasizes the importance of meaningful involvement of older adults with

others, such as friends, family members, neighbors, organizations, and the wider community. While the

public health sector has experience and skill in addressing these components of health for some

populations, it has not traditionally focused such attention on older adults.

The Framework for an Age-Friendly Public Health System developed at the convening includes five key

potential roles for public health.

1. Connecting and convening multiple sectors and professions that provide the supports, services,

and infrastructure to promote healthy aging.

2. Coordinating existing supports and services to avoid duplication of efforts, identify gaps, and

increase access to services and supports.

Page 3 | 18

3. Collecting data to assess community health status (including inequities) and aging population

needs to inform the development of interventions.

4. Conducting, communicating, and disseminating research findings and best practices to

support healthy aging.

5. Complementing and supplementing existing supports and services, particularly in terms of

integrating clinical and population health approaches.

This Framework should not be interpreted as a prescriptive guide to action or a declaration of the public

health sector’s oversight of such activities. Not every community will need public health to assume each

of these roles. In numerous instances, other organizations may already be actively engaged in such work

and the public health sector’s contributions may be unnecessary, limited, or primarily in support of the

efforts of others. The participants emphasized the importance of the many organizations and sectors

outside of public health with long and dedicated histories of providing services to older adults and

supporting healthy aging. The advancement of the public health sector’s work in this arena needs to be

guided by, and in partnership with, such organizations. Furthermore, public health organizations likely

will lack the sufficient resources to engage in all such activities and will need to carefully and

thoughtfully determine how and where to focus their energies. Nonetheless the convening participants

believed that the Framework offered a useful articulation of the potential contributions that the sector

should consider as it embraces a larger role in optimizing the health of older adults.

Aging and Public Health

There is a growing momentum for public health to contribute to programs, policies, and innovative

interventions to promote health and well-being for people as they age. While public health efforts are

partly responsible for the dramatic increases in longevity over the twentieth century,

ii

historically there

have been limited collaborations across the public health and aging fields. Older adults were not central

to the public health agenda when public health emerged in cities in the 19th century.

iii

Similarly, in the

mid-20th century, many federal and state policies to assist older adults to remain independent in the

community, including Medicare, Medicaid, and the Older Americans Act, did not explicitly call for a

role for public health organizations. Over the past 50 years, there have been some steps towards a more

collaborative approach, such as the formation of the Aging and Public Health section of the American

Public Health Association in 1978, or the mandated role for the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) in providing disease prevention and health promotion services offered through the

Older Americans Act in 1987.

iv

However, it is rare when local, state or federal public health agencies

have dedicated funding or develop initiatives targeting adults ages 65 and over.

In recent decades, the aging network, comprised of 56 State Units on Aging (SUAs), 655 Area Agencies

on Aging (AAAs), 243 Indian Tribal and Native Hawaiian Organizations, and thousands of service

providers and volunteers, has increasingly focused on prevention and wellness. The 2010 passage of the

Affordable Care Act (ACA) is shifting the health care system to one with a broadened focus on

prevention, wellness, and health, rather than only disease and injury. As mandated by the ACA, in 2011,

the National Prevention Council released the National Prevention Strategy with an overarching goal of

increasing the number of Americans who are healthy at every stage of life. In 2016, the Council

produced Healthy Aging in Action, which highlights current programs that are advancing the National

Page 4 | 18

Prevention Strategy specifically for older adults. Central to this report is the need for multi-sector

collaborations to achieve a goal of healthy aging.

Public health needs to be a critical partner in these efforts. Over the 20th century, public health played a

crucial role in adding years to life. In the 21st century, public health can play a crucial role in adding life

to years.

Demographic Changes and an Aging Society

Demographic changes make it critical for all sectors and professions, including those that have not

traditionally focused on older adults, to consider the needs of our aging society. In 1900, about three

million Americans, representing 4% of the total population, were ages 65 and over. By 2014, that

number had risen to 46 million, around 15% of the U.S. population. The oldest members of the baby

boom generation turned 65 in 2011, commencing a rapid increase in the number of older adults that will

continue until at least 2030. By that time, about one in five Americans will be 65 or older for the

foreseeable future.

v

This rise in the number and proportion of older adults only presents part of the picture, as there are

substantial variations within the older adult population. An increasing diversity along health and

sociodemographic dimensions means that policies and programs designed to meet the needs of older

adults must consider the needs and preferences of different subpopulations.

First, while the term “older adults” often refers to anyone over the age of 65 (or 60 for some programs),

there are differences in health and service needs between younger older adults and the “oldest old,”

comprised of those ages 85 and older. For example, while about one in eight people age 65 and older has

been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, almost half of the oldest old has this disease.

vi

The 85 and

older population is projected to grow from six million in 2014 to 20 million by 2060.

vii

Second, the demographic composition of the older adult population is rapidly changing. For example,

the older adult population, much like the rest of the US population, is becoming more racially and

ethnically diverse. In 2014, 78% of older adults were non-Hispanic White, 9% were African American,

8% were Hispanic of any race, and 4% were Asian. By 2060, the percentage of non-Hispanic whites is

expected to drop to 55%, while the proportion of other racial groups will increase, with 22% of the

population Hispanic, 12% African American, and 9% Asian.

viii

These changes are important because of

racial and ethnic inequities in health and access to resources, as well as cultural differences in

expectations of informal and formal care.

Third, there are substantial variations in social and economic well-being among the older adult

population. Older adults are less likely to live below the poverty line than other age groups, with 10% of

those age 65 and over living in poverty in 2014,

ix

but this may not be an accurate indicator of economic

vulnerability in later life. Poverty increases with age, suggesting that the growth of the oldest old may

also lead to an increase in the number of older adults living in poverty. Additionally, because the federal

poverty line fails to take into account all of older adults’ basic living costs, including those for health

care and transportation, this measure underestimates the extent of financial need among this segment of

the population. Indeed, research using a more age-specific measure of financial resources found that in

Page 5 | 18

California more than half of older adults living alone and more than one-quarter of older couples lack

adequate income to cover basic expenses.

x

Challenges and Opportunities of an Aging Society

Existing systems and structures in the United States face major challenges in promoting the health and

wellbeing of this growing and increasingly diverse older adult population.

First, the United States lacks an overall system of long-term care, offering instead an uncoordinated and

often confusing patchwork of community-based programs with varying eligibility criteria, costs, and

availability. Long-term care is expensive for older adults, their families, and society. In the most recent

estimates available, spending on long-term services and supports (LTSS) totaled nearly $220 billion in

2012,

xi

a figure that may quadruple by 2050.

xii

Even with these high costs, LTSS are unable to fully

meet older adults’ needs. For example, 58% of those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, a

population that often experiences health problems and disability, indicate they have unmet needs for

care for activities of daily living.

xiii

Second, family members and other informal caregivers are the largest sources of support for older adults

in this country, but changes in family structure and social roles limit the ability of family members to

provide that support. Decreased fertility rates, greater numbers of women in the workforce, and the

geographic dispersion of families have reduced the availability of younger family members to help older

adults with their daily activities.

xiv

While in 2013, there were more than 14 adults of prime caregiving

age (i.e., ages 45-64) for every person over the age of 85, by 2050, this ratio will drop to less than four

to one.

xv

If these trends continue, older adults may have fewer sources of instrumental assistance,

emotional support, and social interaction in the future.

Third, the physical and social infrastructures of many cities and towns in the United States create

barriers to healthy aging. For example, few older adults live in mixed-use neighborhoods where they can

safely walk to a grocery store, pharmacy, or other services and gathering places, and about one-third of

older adults do not have any public transportation where they live.

xvi

In addition, many places lack social

features that could help older adults remain connected to their community, such as adult learning

programs, volunteer activities that utilize their skills and experience, and other enjoyable and

meaningful activities.

While these challenges need to be addressed, the aging of the US population is also creating

opportunities for older adults and their families and communities. Too often, the changing demographics

of the United States are equated to a crisis, reflected in the use of the term “silver tsunami,” rather than

as a success story of improved health, well-being, and longevity. Today’s older adults, on average, have

higher educational attainment, better overall health, and lower disability rates than previous

generations.

xvii

Older adults serve their communities formally by engaging in volunteer activities, such

as tutoring in an elementary school, maintaining a community garden, registering residents to vote, and

working at a food bank, among others. Older adults also make valuable contributions through informal

roles. For example, 19% of all of those who provide care to an adult with health or functional limitations

are age 65 or older

xviii

and 2.7 million older adults are the primary caretakers of their grandchildren.

xix

Page 6 | 18

An Age-Friendly Paradigm Shift

In response to the challenges and opportunities of our aging society, in recent decades, there has been a

growing emphasis on making existing systems and structures more “age-friendly.” This approach

acknowledges the importance of assessing the fit between individual needs and preferences with their

surrounding environment.

One prominent example is the movement to create more age-friendly communities, defined as those that

encourage “active aging by optimizing opportunities for health, participation, and security in order to

enhance quality of life as people age.”

xx

Age-friendly community initiatives typically focus on

modifying the physical and social infrastructure to support older adults’ health, well-being, and ability to

age in place. Age-friendly community features typically include two types of programs, policies, and

infrastructure: 1) those that focus specifically on the needs of older adults, and 2) those that benefit older

adults as well as community residents at other stages of the life course.

xxi

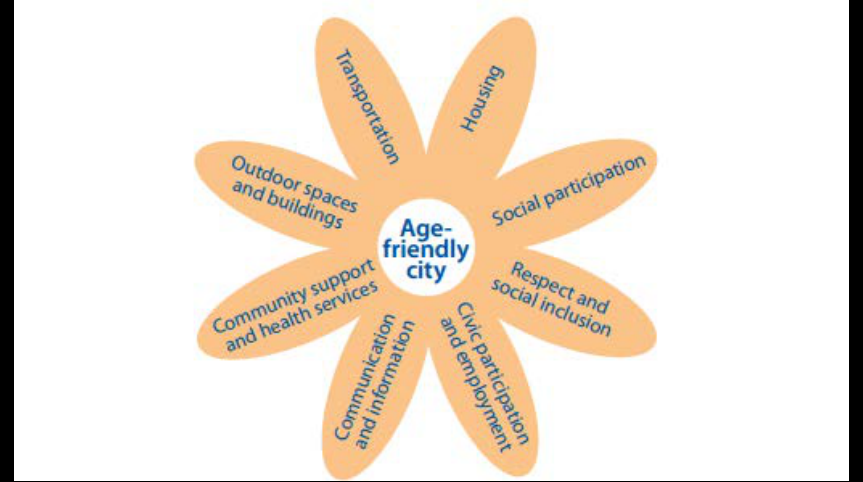

For example, the World Health

Organization’s Global Network for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities program

xxii

began in 2006 in

33 cities in 22 countries and now has more than 287 members (including US affiliates through the

AARP Network of Age-Friendly Communities). Based on information gathered from the scholarly

literature and more than 150 focus groups with older adults, caregivers, and service providers around the

world, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified eight core community features for an age-

friendly community (see Figure 1 on page 7). These features include those under the purview of public

and private sectors, as well as multiple disciplines and professions.

Figure 1: WHO Age-Friendly Community Features

Source: WHO global network for age-friendly cities and communities. (2014). Retrieved from:

http://www.who.int/ageing/age_friendly_cities_network/en

Page 7 | 18

There has also been movement toward the development of age-friendly health systems, spurred not only

by the projected increase in demand for health care as the proportion of older adults rises, but also by

innovations in health care delivery post implementation of the ACA, such as person-centered care,

bundled payments, and innovations addressing the social determinants of health.

xxiii

Age-friendly health

systems aim to provide evidence-based care via a trained geriatric workforce, coordinate with a full

range of community-based services, and meaningfully engage older adults and their families. The John

A. Hartford Foundation, for example, has made the expansion and evaluation of an age-friendly health

system approach a major priority, with the ultimate goal of developing effective strategies to improve

health outcomes and reduce costs.

An age-friendly public health system aligns with and complements these existing age-friendly

initiatives. It identifies the key capacities that public health potentially can bring to support ongoing

efforts by the aging and health care fields. It also highlights the ways public health expertise can inform

the development and implementation of new policy and programmatic interventions.

A Framework for an Age-Friendly Public Health System

The Framework for an Age-Friendly Public Health System identifies five key potential roles for public

health, with particular attention to the ways public health can support, complement, or enhance aging

services.

1. Connecting and convening multiple sectors and professions that provide the supports, services,

and infrastructure to promote healthy aging.

Addressing the full range of individual and community needs to support healthy aging requires the

active contribution of a variety of stakeholders. Many different organizations and professionals are

already working to support healthy aging, yet they often operate in silos with limited opportunities to

communicate with each other. The first potential role of public health is to connect and convene the

multiple sectors and professions that provide the supports, services, and infrastructure to promote

healthy aging.

One example that highlights this role is in promoting and supporting physical activity. Regular physical

activity reduces the risk of chronic conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, prevents

cognitive and functional decline, and decreases the likelihood of falls and subsequent injury,

xxiv

however

only a minority of older adults meets recommendations such as the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines

for Americans.

xxv

There are numerous barriers to regular physical activity in later life, including

restricted access to indoor and outdoor recreational facilities, concerns about neighborhood safety,

limited individual knowledge about the benefits of exercise,

xxvi

and the absence of walkable

neighborhood features (e.g., well-maintained sidewalks, raised crosswalks, speed bumps, and a variety

of food and shopping destinations).

xxvii

Public health could bring together the multiple actors that could

alleviate these barriers, including law enforcement, public works, parks and recreation, city planning,

local businesses, physicians, senior centers, and other community groups. As a connector and convener,

public health can promote communication across sectors and facilitate the sharing of knowledge and

resources.

Page 8 | 18

Another example is the need to address social isolation in later life. Social isolation can involve an

objective separation from a social network, such as living alone, or more subjective feelings of

loneliness.

xxviii

Approximately 12 million adults over the ages of 65 live alone,

xxix

and studies report that

15% to 45% of older adults experience loneliness.

xxx,

xxxiixxxi,

Social isolation can negatively affect

quality of life and contribute to an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.

xxxiii,

xxxiv

Public health can

work with community-based organizations, such as senior centers, community centers, and YMCAs, to

address loneliness and social isolation by providing opportunities for social interaction and the

development of new friendships. Public health professionals can also partner with “Villages,” grassroots

consumer-driven community-based organizations that aim to promote aging in place by combining

services, participant engagement, and peer support. First emerging in the early 2000s, currently there are

more than 200 Villages in the United States in operation or development.

xxxv

Studies suggest that

Villages are a promising approach to increasing members’ social engagement,

xxxvi

and connecting with a

variety of formal and informal community supports (including those offered by public health

departments) plays a critical role in their ability to do so.

When convening sectors, professions, and organizations, public health typically leverages its seat at the

table to ensure a focus on prevention and on policy, systems, and environmental change to support the

goals of healthy aging efforts. A greater focus on prevention can help forestall declines in health and

well-being, such as falls prevention and initiatives to promote physical activity or brain health. A focus

on policy, systems, and environmental change complements the efforts to address the needs of

individual older adults by focusing on improvements that impact entire populations or communities.

2. Coordinating existing supports and services to avoid duplication of efforts, identify gaps, and

increase access to services and supports.

Navigating the wide variety of supports and services for older adults can be confusing and

overwhelming for older adults, their families, and other professionals. Supports and services are offered

by a range of providers in different locations and settings, with different funding sources and variations

in eligibility requirements. A second critical role for public health is therefore to coordinate existing

supports and services to avoid duplication of efforts, identify gaps, and increase access to services and

supports. If there are available resources, health departments can create an aging specialist role to

facilitate this coordination and ensure that older adults are not overlooked in any other public health

programming or research.

It should be noted that aging professionals and organizations, including AAAs, are working to avoid

duplication of efforts, reduce unmet need for supports, and maximize the efficient use of existing

resources. Public health can be a particularly effective coordinator to address the barriers within its areas

of expertise. For example, many older adults do not receive preventive health services, such as those

recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, including screenings, behavioral health

monitoring and counseling, and immunizations.

xxxvii

With 90% of flu-related deaths occurring among

those ages 65 and over,

xxxviii

there is a critical need to improve the availability and acceptability of such

preventive services. Public health has been a key partner in the work of Vote & Vax, a national initiative

that has received support from the CDC and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to provide flu

vaccines in polling places. Bringing together multiple sectors, including public health, pharmacy, and

nursing, Vote & Vax has demonstrated success in improving vaccination rates among those with access

barriers to the more traditional vaccination sites of physician offices or pharmacies.

xxxix

This program

Page 9 | 18

thus fills a critical gap in service delivery and highlights a creative approach to improving population

health.

3. Collecting data to assess community health status (including inequities) and aging population

needs to inform the development of interventions.

All sectors are becoming increasingly data driven to ensure that they have all the information they need

to address their target populations and target problems. A third role for public health is to call attention

to the needs and assets of a community’s aging population to inform the development of interventions

through community-wide assessment, a critical step to set goals and define measures for health

improvement.

Public health can help document population and community health status by collecting and analyzing

data, including data from multiple sectors and sources. While public health has often not focused on

older adults in these activities, there are multiple opportunities. One example is the Behavioral Risk

Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) administered by the CDC, which includes two modules that states

can use to assess and track two issues critical to the health and well-being of older adults: the cognitive

decline module and the caregiver module. These two modules are currently voluntary and are in use in

35 states (21 caregiver and 21 cognitive decline, with seven states doing both modules). Public health

departments can advocate for wider implementation of these modules in states that have not adopted

these modules, and can analyze and disseminate the data in states that have.

Another example is the Survey of the Health of All the Population and Environment (SHAPE),

conducted in 2014 in six Minnesota counties. This study’s results have helped inform local priorities for

a number of populations, including older adults. For example, results on health and functioning were

included in a 2017 publication from Saint Paul – Ramsey County Public Health Department, Healthy

Aging: A Public Health Framework.

As another example, public health can provide important information about older adults using hotspot

analysis, a technique to examine the geographic distribution of populations, features, or events. Such

data can be essential in mapping neighborhoods in which older adults are at a higher risk for a fall or

have less access to a grocery store. This essential data can then be analyzed and disseminated to target

audiences in easy-to-use fact sheets.

Older adults often experience higher rates of injury and death and lower rates of economic recovery

following major natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and tornadoes.

xl

Therefore, existing

datasets and hotspot analysis showing areas with high concentrations of older adults, particularly those

living alone or with a health challenge, could inform emergency preparedness. The Department of

Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response developed

the emPOWER Initiative through a partnership with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The emPOWER Initiative provides federal data and mapping tools to local and state public health

departments to help them identify vulnerable populations who rely upon electricity-dependent medical

and assistive devices or certain health care services, such as dialysis machines, oxygen tanks, and home

health services. The emPOWER Map is a public and interactive map that provides monthly de-identified

Medicare data down to the zip code level, and an expanded set of near real-time hazard tracking

services. Together, this information provides enhanced situational awareness and actionable information

Page 10 | 18

for assisting areas and at-risk populations that may be impacted by severe weather, wild fires,

earthquakes, and other disasters. Public health and emergency management officials, AAAs, and

community planners can use emPOWER to better understand the types of resources that may be needed

in an emergency. For instance, these data can inform power restoration prioritization efforts, identify

optimal locations and needs for shelters, determine transportation needs, and anticipate potential

emergency medical assistance requests. The data are also used to conduct outreach prior to, during, or

after an incident, public health emergency, or disaster that may adversely impact at-risk populations.

The public health sector may also bring an asset-based approach to community assessment, documenting

the collective resources of older adults, their families, and their communities. This aligns with the work

of aging services and other providers to move away from an emphasis on deficits and toward a

recognition of strengths, skills, and capacities.

Public health can provide health care systems with critical info about older adults in their surrounding

communities as part of Community Health Needs Assessments, which are now mandated for all tax-

exempt hospitals by the ACA. Nonprofit hospitals are now required at least once every three years to

assess and prioritize the health needs of their geographic community, and then develop and implement

action steps to address those needs.

xli

At least one local, state, or regional public health department must

be involved in this process. Public health can thus call attention to the needs of older adults and ensure

programs and resources are dedicated to this population.

4. Conducting, communicating, and disseminating research findings and best practices to

support healthy aging.

Rigorous translational research can empower individuals to engage in healthy behaviors, support the

provision of effective clinical services, and create safe and healthy community environments. Public

health researchers, policymakers, and practitioners can play a key role in supporting healthy aging by

conducting, communicating, and disseminating research findings and best practices, particularly in terms

of prevention and population health.

For example, public health is already serving this function in the area of cognitive health.

Approximately 10%, or 3.6 million, of all Medicare beneficiaries over the age of 65 living in the

community had some form of dementia in 2011.

xlii

CDC’s Healthy Brain Initiative promotes a role for

public health in maintaining or improving cognitive functioning in later life. As part of this initiative,

CDC worked with the Alzheimer’s Association to develop a guide (first in 2007, then updated in

2013

xliii

) outlining action items for public health officials to promote cognitive health, address cognitive

impairment, and support dementia caregivers. A key component of this initiative is supporting applied

research and translating evidence into practice for providers and policymakers. Public health can also

assist with neurocognitive disorder public awareness campaigns around modifiable risk factors, signs of

disease progression, strategies for addressing changes in behavior, and community supports. Public

health can also support the development and implementation of evidence-based programs and evidence-

informed policies.

In addition, there is a large body of research concerning healthy aging, yet limited clearinghouses for

interested parties to find best practices or resources. Public health organizations may provide central

locations for information on healthy aging, including best practices, tool kits, and research. The ready

Page 11 | 18

availability of such a site can assist other sectors and professions in their efforts to address the needs of

older adults.

5. Complementing and supplementing existing supports and services, particularly in terms of

integrating clinical and population health approaches.

The fifth proposed role for public health is complementing and supplementing existing supports and

services, particularly in terms of integrating clinical and population health approaches. Existing public

health programs address a wide range of health issues, from infectious disease to chronic disease; from

education campaigns that reach the general public to targeted and focused home visits by educators;

from the enforcement of environmental regulations addressing long-term health risks, such as lack of

clean air and water, to the response to rare and catastrophic events. Furthermore, public health is focused

on the entire life course, providing programs and policies, such as maternal and child health, workplace

safety, and tobacco-free initiatives, that ultimately support healthy aging later in life. Each of these

current activities could be assessed to determine if it is adequately meeting the needs of older adults and,

when necessary, modified to better do so.

For example, aging services are beginning to recognize the value of Community Health Workers

(CHWs), a public health approach that has long been working with populations with limited access to

formal health and social services. CHWs are trusted members of a community and conduct outreach,

provide education, and serve as a liaison to formal systems of support. Preliminary research indicates the

promise of CHWs for reducing health care costs, supporting transitions back home from the hospital,

and connecting low-income senior housing residents to community services.

xliv

This may be a

particularly effective strategy to address health inequities.

Public health can also complement existing programs for informal caregivers providing assistance to

older adults with disabilities. Community-based support for caregivers are often fragmented from each

other and disconnected from the health and long-term care systems.

xlv

The National Family Caregiver

Support Program, created by the federal Older Americans Act Amendments of 2000, provides a range of

services, including counseling, case management, respite care, and training, particularly in terms of

adapting to the caregiver role and developing strategies for self-care. Public health can provide critical

education and training on performing the tasks needed to support older care recipients, such as safely

bathing or transferring from a bed to a chair, or addressing the behavioral changes associated with

dementia.

Barriers to Creating an Age-Friendly Public Health System

While there was a clear consensus at the convening about the value of an age-friendly public health

system, there was also a recognition that this expanded focus will be accompanied by barriers.

The first barrier is the need to break down professional and disciplinary silos. Promoting a public health

strategy to healthy aging requires a collective impact approach that recognizes that the solutions to

complex social problems do not emerge from the activities of a single individual, social service agency,

or sector, but rather from the activities of multiple entities, including businesses, nonprofits,

governments, and the general public.

xlvi

However, forming and maintaining collaborations of diverse

partners requires time, energy, dedication, and funding. Helping stakeholders who have not traditionally

Page 12 | 18

focused on older adults recognize the role that they can play to promote healthy aging across the life

course will be an additional challenge. As noted above, those in the public health sector are often

accustomed to convening and facilitating diverse collaborations and may be well suited to bring together

the wide range of stakeholders needed to promote healthy aging.

The second barrier relates to the persistence of ageist norms. In the United States, older adults are often

seen primarily as needy or helpless patients rather than as full human beings with strengths as well as

limitations, who can give as well as receive. Such limited perceptions foster the view of the aging of the

US population as a problem. At the same time, with a few notable exceptions, ageism also prevents the

needs of older adults from becoming a priority at the local, state, and federal levels. In an effort to

combat the deleterious effects of ageism, eight leading aging organizations (AARP, American

Federation for Aging Research, American Geriatrics Society, American Society on Aging,

Gerontological Society of America, Grantmakers in Aging, National Council on Aging, and National

Hispanic Council on Aging) have partnered for the Reframing Aging Project. By incorporating the

needs and assets of the aging population into its own priorities, public health can serve as a model for

other sectors and professions to embrace an aging-in-all-policies-and-practices approach. Through

assessment and research activities that complement the work of others, public health can highlight the

ways older adults are assets to their families and communities, and promote the message that the aging

of the population is a success story and not a crisis.

Finally, there is clearly a need for more funding from both the public and private sectors to support

healthy aging. Indeed, as the number of older adults continues to grow in this country, the amount of

public health and social service funding from the federal, state, and local levels is shrinking.

Furthermore, funding is rarely available for the larger scale, collective impact activities required to fully

support healthy aging. Grants are often given to one specific agency to support one specific intervention

for one specific health or social problem. Promoting healthy aging across diverse populations will likely

require a substantial investment of financial and human resources. However, stakeholders can develop

strategies to maximize existing resources and identify new sources of support. These include focusing

on relatively low-cost policies and programs, enlisting the participation of multiple stakeholders,

considering how existing policies and programs can meet the needs of older adults, and braiding

together funding from multiple sectors.

Next Steps

Despite these barriers, this is the time for public health to contribute to programs, policies, and

innovative interventions to promote health and well-being as people age. Given the changing

demographics and complex health-related needs of older adults, the public health sector should fully and

comprehensively make such work a priority. The Framework for an Age-Friendly Public Health System

highlights five key potential roles for public health. While this summary offers some examples of each, a

key next step is a more systematic approach to develop and disseminate case studies, best practices, and

tool kits.

Public health has a lot to offer – it has long utilized prevention and health promotion strategies that can

be usefully deployed. The Florida convening demonstrated that many aging service organizations are

eager to have partners from public health and other fields. Healthy aging depends on both upstream and

downstream efforts. Both efforts require the involvement of diverse sectors, disciplines, and professions

Page 13 | 18

and the consideration of the ways in which their policies, programs, and infrastructure affect older

adults. To ensure such policies are evidence-informed, aging and public health need to communicate,

collaborate, and leverage each other’s strengths and areas of expertise.

Page 14 | 18

Participant List

John Auerbach

President and CEO

Trust for America’s Health

Kathy Black

Professor

University of South Florida, Sarasota – Manatee

Alice Bonner

Secretary

Mass. Executive Office of Elder Affairs

alice.bonner@state.ma.us

Debra Burns

Director, Centers for Health Equity and

Community Health

Minnesota Department of Health

Terry Fulmer

President

The John A. Hartford Foundation

Trina Gonzalez

Program Officer

Milbank Memorial Fund

Chuck Henry

Administrator

Florida State Department of Health, Sarasota

Randall Hunt

President & CEO

Senior Resource Alliance

Kathryn Hyer

Professor

University of South Florida

Jeffrey Johnson

Director

AARP Florida State

Jennifer Johnson

Division Director, Public Health Statistics and

Performance Management

Florida Department of Health

Paul Katz

Professor & Chair, Department of Geriatrics

Florida State University

Aldiana Krizanovic

Senior Health Policy Consultant

Florida Blue Foundation

Jewel Mullen

Former Principal Deputy Assistant for Health

Health and Human Services

jmullen@livinglongerbetter.net

Celeste Philip

Surgeon General and Secretary of Health

Florida Department of Health

celeste.philip@flhealth.gov

Susan Ponder-Stansel

President

Florida Council on Aging

Richard Prudom

Deputy Secretary/Chief of Staff

Department of Elder Affairs

Sharon Ricks

Regional Health Administrator

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Page 15 | 18

Laurence Solberg

Chief, Division of Geriatrics

University of Florida

Nora Super

Chief, Programs and Services

National Association of Area Agencies on

Aging

Michele Walsh

Associate Director for Policy and

Communication

Division of Population Health,

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Staff and Consultants

Ashley Ashworth

Former Health Policy Analyst

Trust for America’s Health

Abby Dilley

Vice President of Program Development

RESOLVE

Sherry Kaiman

Strategic Partner

RESOLVE

LaToya Ray

Office Manager and Grants Manager

Trust for America’s Health

Partners

The John A. Hartford Foundation

The John A. Hartford Foundation, based in New York City, is a private, nonpartisan, national

philanthropy dedicated to improving the care of older adults. The leader in the field of aging and health,

the Foundation has three areas of emphasis: creating age-friendly health systems, supporting family

caregiving, and improving serious illness and end-of-life care.

Milbank Memorial Fund

The Milbank Memorial Fund is an endowed operating foundation that works to improve the health of

populations by connecting leaders and decision makers with the best available evidence and experience.

Founded in 1905, the Fund engages in nonpartisan analysis, collaboration, and communication on

significant issues in health policy.

Page 16 | 18

Endnotes

i

National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council (2016). Healthy Aging in Action: Advancing

the National Prevention Strategy. Modified from Rowe, JW, Kahn, RL (1998). Successful Aging. New York:

Pantheon. And Marshal, VW, Altpeter, M (2005). Cultivating social work leadership in health promotion and aging:

Strategies for active aging interventions. Health & Social Work, 30, 135-144. Retrieved from:

https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/about/healthy-aging-in-action-final.pdf.

ii

Cutler, D, Miller, G (2005). The role of public health improvements in health advances: The twentieth-century

United States. Demography, 42(1), 1-22.

iii

Kane R. Public health paradigm. In: Hickey T, Speers MA, Prohaska TR, eds. Public Health and Aging.

Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1997:3–16.

iv

Anderson, L, Goodman, RA, Holtzman, D, Posner, S, Northridge, ME (2012). Aging in the United States:

Opportunities and Challenges for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 102, No. 3, p. 393.

v

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics (2016). Older Americans 2016: Key indicators of well-

being. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

vi

Alzheimer’s Association. 2014 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Retrieved from http://

www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2014.pdf.

vii

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2016: Key indicators of well-being.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

viii

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2016: Key indicators of well-being.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

ix

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2016: Key indicators of well-being.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

x

Wallace, SP, Padilla-Frausto, D I, Smith, SE (2010). Older adults need twice the federal poverty level to make

ends meet in California (Policy Brief 2010-8). Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

xi

National Health Policy Forum (2014). National spending for long-term services and supports, 2012. Retrieved

from: https://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LTSS_03-27-14.pdf.

xii

Burman, LE, Johnson, RW (2007). A proposal to finance long-term care services through Medicare with an

income tax surcharge. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

xiii

Komisar, HL, Feder, J, Kasper, JD (2005). Unmet long-term care needs: An analysis of

Medicare-Medicaid dual eligible. Inquiry, 42(2), 171-182.

xiv

Spillman, BC, Pezzin, LE (2000). Potential and active family caregivers: Changing networks and the “sandwich

generation.” Milbank Quarterly, 78(3), 347–374.

xv

Redfoot, D, Feinberg, L, Houser, A (2013). The aging of the baby boom and the growing

care gap: A look at future declines in the availability of family caregivers. Washington,

DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

xvi

Rosenbloom, S, Herbel, S (2009). The safety and mobility patterns of older women: Do current

patterns foretell the future? Public Works Management & Policy, 13(4), 338–353.

xvii

West, LA, Cole, S, Goodkind, D, He, W (2014). 65+ in the United States: 2010. Retrieved from:

https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p23-212.pdf.

xviii

AARP Public Policy Institute and National Alliance for Caregiving (2015). Caregiving in the US. Retrieved

from: http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf.

xix

US Census Bureau (2014). Coresident grandparents and their grandchildren: 2012. Retrieved from:

https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p20-576.pdf .

xx

World Health Organization (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. Geneva, Switzerland:

World Health Organization.

xxi

Alley, D, Liebig, P, Pynoos, J, Banerjee, T, Choi, IH (2007). Creating elder-friendly communities: Preparations

for an aging society. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49(1-2), 1-18.

xxii

World Health Organization (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. Geneva, Switzerland:

World H

ealth Organization.

Page 17 | 18

xxiii

Fulmer, T, & Berman, A (2016). Age-friendly health systems: How do we get there? Health Affairs Blog. DOI:

10.1377/hblog20161103.057335.

xxiv

Nelson, M.E, Rejeski, WJ, Blair, SN, Duncan, PW, Judge, JO, King, AC, ... & Castaneda-Sceppa, C, et al

(2007). Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports

Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 116(9), 1094.

xxv

US Department of Health and Human Services. HP2020 Objective Data Search website. Physical Activity.

http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-

Data?f%5B%5D=field_topic_area%3A3504&pop=&ci=&se=.

xxvi

Schutzer, KA, Graves, BS (2004). Barriers and motivations to exercise in older adults. Preventive

medicine, 39(5), 1056-1061.

xxvii

Clark, DO (1999). Identifying psychological, physiological, and environmental barriers and facilitators to

exercise among older low income adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 5(1), 51-62.

xxviii

Golden, J, Conroy, RM, Bruce, I, Denihan, A, Greene, E, Kirby, M, Lawlor, BA (2009). Loneliness, social

support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. International Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry, 24(7), 694-700.

xxix

US Census Bureau. (2014). 65+ in the United States: 2010. (Publication P23-212). Washington, DC: U.S.

Government Printing Office.

xxx

Golden, J, Conroy, RM, Bruce, I, Denihan, A, Greene, E, Kirby, M, Lawlor, BA (2009). Loneliness, social

support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. International Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry, 24(7), 694-700.

xxxi

Lauder, W, Sharkey, S, Mummery, K (2004). A community survey of loneliness. Journal of Advanced Nursing,

46(1), 88-94.

xxxii

Pinquart, M, Sorensen, S (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied

Social Psychology, 23(4), 245-266.

xxxiii

Lyyra, T, Heikkinen, R (2006). Perceived social support and mortality in older people.

Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 61, S147-S152.

xxxiv

Bassuk, SS, Glass, TA, Berkman, LF (1999). Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in

community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131, 165–173.

xxxv

Village to Village Network (n.d.). Village map. Retrieved from:

http://www.vtvnetwork.org/content.aspx?page_id=1905&club_id=691012

xxxvi

Graham, CL, Scharlach, AE, Price Wolf, J (2014). The impact of the “Village” model on health, well-being,

service access, and social engagement of older adults. Health Education & Behavior, 41(1S), 91S-97S.

xxxvii

Healthy People 2020 (OA-1 and OA-2, respectively). http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-

objectives/topic/older-adults/objectives#4976.

xxxviii

Halloran, L (2013). Health promotion and disability prevention in older adults. Journal for Nurse

Practitioners, 9(8), 546–547. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2013.05.023.

xxxix

Shenson, D, Moore, RT, Benson, W, Anderson, LA (2015). Polling places, pharmacies, and public health:

Vote & Vax 2012.

xl

Bolin R, Klenow DJ. Response of the elderly to disaster: An age-stratified analysis. Intl J Aging and Human

Development 1982–3;16(4):283–297.

xli

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office for State, Local, and Territorial Support (2013). Summary

of the Internal Revenue Service’s April 5, 2013, notice of proposed rulemaking on community health needs

assessment for charitable hospitals. Retrieved from: http://www.astho.org/Summary-of-IRS-Proposed-Rulemaking-

on-CHNA/.

xlii

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. (2016). Older Americans 2016: Key indicators of well-

being. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

xliii

Alzheimer’s Association and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). The Healthy Brain

Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013-2018. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s

Association. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/healthybrain/roadmap.htm.

xliv

Rush, CH (2015). Community health workers moving to new roles as more seek to age in place. AgeBlog.

Retrieved from: http://www.asaging.org/blog/community-health-workers-moving-new-roles-more-seek-age-place.

Page 18 | 18

xlv

Riggs, JA (2003). A family caregiver policy agenda for the twenty-first century. Generations, 27(4), 68-73.

xlvi

Kania, J, Kramer, M (2011). Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 9(1), 36–41.