Estimating UK investment in intangible

assets and Intellectual Property Rights

Research commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office, and carried out by:

Peter Goodridge, Jonathan Haskel, Gavin Wallis

This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO). Findings and opinions are

those of the researchers, not necessarily the views of the IPO or the Government.

© Crown copyright 2014

2014/36

Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office

'

Contacts: Jonathan Haskel and Peter Goodridge, Imperial College Business

School, Imperial College, London. SW7 2AZ. j.haskel@ic.ac.uk, p.goodridge10@

ic.ac.uk. We are very grateful for financial support for this research from NESTA

and the UK Intellectual Property Office. This work was based on data from the

Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), National Employers Skills Survey

(NESS) and UK Innovation Survey (UKIS), produced by the Office for National

Statistics and supplied by the Secure Data Service at the UK Data Archive. The

data are Crown Copyright and reproduced with the permission of the controller

of HMSO and Queen s Printer for Scotland. The use of the data in this work does

not imply the endorsement of the ONS or Secure Data Service at the UK Data

Archive in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the data. This work uses

research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics

aggregates. We thank Tony Clayton of the IPO for very helpful suggestions.

Views expressed in this paper represent those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect those of affiliated institutions. All errors are of course our own.

ISBN: 978-1-910790-03-8

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and

Intellectual Property Rights

Published by The Intellectual Property Office

30

th

September 2014

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

© Crown Copyright 2014

You may re-use this information (excluding logos)

free of charge in any format or medium, under the

terms of the Open Government Licence. To view

this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.

uk/doc/open-government-licence/

or email: [email protected].uk

Where we have identified any third party copyright

information you will need to obtain permission from

the copyright holders concerned.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be

sent to:

The Intellectual Property Office

Concept House

Cardiff Road

Newport

NP10 8QQ

Tel: 0300 300 2000

Fax: 01633 817 777

e-mail: [email protected].uk

This publication is available from our website at

www.ipo.gov.uk

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

3

Abstract

This report represents an update on the estimates of UK Intangible investment we published at

the end of March 2014. These revisions have been driven by methodological improvements

centered on improved estimates of investment in human capital.

The report contains updated estimates of (a) the level of UK market sector investment in

knowledge assets and (b) the proportions of those investments protected by Intellectual Property

Rights (IPRs). Estimates for knowledge investment are produced as part of the UK Innovation

Index. Our main findings are: 1) In 2011 the UK market sector invested £126.8bn in knowledge

assets, compared to £88bn in tangible assets; 2) Since the recession of 2008-9, intangible

investment has recovered and grew in 2010-11. In contrast investment in tangible assets has

fallen; 3) In 2011, 50% (£63.5bn) of knowledge investment in the UK market sector was

protected by IPRs 4) The majority of IPR investment is on assets protected by copyright (47%),

trademarks (22%) and unregistered design rights (18%).

1. Introduction

This report builds on previous work which estimated UK market sector investment in knowledge

capital (Goodridge, Haskel and Wallis (2012)) and the proportions of those investments protected

by formal intellectual property rights (IPRs) (Farooqui, Goodridge and Haskel (2011)). Investment

in knowledge, or intangible, capital adds to the stock of intellectual property (IP) in the economy.

Not all of that investment is protected by formal Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) such as

copyright and patents: investments in software are protected, but investments in workforce

training are not. Thus this report attempts to answer the following questions: (a) how much

does the UK invest in knowledge assets? and (b) what proportion of UK knowledge investment

is protected by formal IPRs?

To answer these questions we first estimate UK market sector

1

investment in knowledge or

intangible assets, using the comprehensive framework outlined in Corrado, Hulten et al. (2005),

hereafter CHS. Second, we apportion various knowledge investments to investments in IPRs.

Improvements to the data and methodologies used to estimate investment in artistic originals in

the national accounts, based on our previous work (Goodridge and Haskel 2011; Goodridge,

Haskel et al. 2012), means that, when combined with official UK software investment data

(Chamberlin, Clayton et al. 2007), we can offer a better estimate for UK investment in copyright-

protected assets. As well as other categories of knowledge assets, our dataset includes

estimates of investment in research and development (‘R&D’), ‘Branding’ (made up of

‘Advertising’ and ‘Market Research’) and ‘Architectural and Engineering Design’ (AED), upon

which we base our estimates for investment in ‘Patents’, ‘Trademarks’ and ‘Design Rights’

(both registered and unregistered). Of course, not all such investment is protected by IPRs, so

We define the market sector as sections A-K, MN, & RST according to the 2007 Standard Industrial Classification,

thereby excluding Real Estate Activities (L), Public Administration & Defence (O), Education (P) and Health and

Social Work (Q).

1

4

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

we use data from the Community Innovation Survey (CIS) to estimate the proportion that is

protected. W

e estimate that: 38% of R&D is protected by patents and 3% by design registration;

and 11% of AED is protected by design registration and 2% by patents.

It is worth noting that our estimates of IPR-protected investment are not measures of all UK

spend on IPRs. Rather they are measures of all long-lived spending on creating knowledge

assets, which contribute to the production of output over a period of greater than one year, and

which is protected by formal IP mechanisms.

Our main findings are as follows:

1. In 2011, we estimate that the UK invested £126.8bn in intangible assets compared to

£88bn in tangible assets;

2. Since the recession of 2008-9, intangible investment has recovered and grew in 2010-11.

In contrast investment in tangible assets has fallen;

3. In 2011, we estimate that approximately 50% of UK market sector investment in knowledge

was protected by formal IPRs;

4. Of that investment in IPRs in 2011, we estimate that: 10% was in assets protected by

patents; 47% in assets protected by copyright; 3% in assets protected by design registration;

22% in assets protected trademark; and 18% in assets protected by unregistered design

rights.

This report proceeds as follows. In section 2 we set out our conceptual framework. In section

3 we discuss our methods for measurement in the context of that framework and present our

estimates for UK market sector investment in intangible assets. In section 4 we present our

method and results on: the proportions of UK intangible investment protected by IPRs; and

therefore our estimates of investment in IPR-protected assets. Section 5 concludes.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

5

2. Conceptual Upstream-

Downstream Framework

The following section is a summary of the appropriate conceptual framework to consider

production of, investment in, and consumption of, intellectual property. It is based on the concept

of ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ sectors, as applied in Corrado, Goodridge and Haskel (2011),

where the upstream creates original IP assets and the downstream uses the IP to generate final

output. For example, the upstream could produce film originals which are used by downstream

cinema projectors or television broadcasters, or in the production and distribution of copies, in

the generation of final output. Alternatively the upstream could consist of an R&D (or design) unit

that produces commercial knowledge to be used in the downstream operations sector. This

upstream-downstream framework can be applied to any form of long-lived knowledge that is

used in the generation of final output.

Consider then an economy with an innovation (IP-producing) sector and a final output (IP-using)

sector. The innovation sector (upstream) produces long-lasting knowledge assets which

contribute to production in the final output (downstream) sector. In this economy we may write

N

the value of gross output in the innovation sector as

PN

. This is equal to factor and intermediate

costs in the sector multiplied by any mark-up () over those costs, where represents the

monopoly power earned by the innovator through the ownership of a unique knowledge asset,

which may be formally protected by IPRs:

N LN KNMNRN

P N =

µ

(PL + P K + P M + PR )

(1)

LN

K N

M N

R N

Where:

PL

,

PK

and

PM

are payments for labour, capital and intermediates.

PR

are payments for intangible capital services, for instance royalty payments to use music in the

production of a film original.

Consider next the final output or downstream sector, which uses the innovative good. They could

N

purchase the asset rights (or some component of them) outright, for a cost

PN

(or some

N

R

proportion of

PN

). Alternatively they could rent the good by paying a licence fee,

PR

, for T

years to the innovation sector. Capital market equilibrium implies that:

T

R

N

PR

t

PN=

∑

t

=1

( )

1 r

(2)

t

+

Where R is the stock of knowledge from which they rent; using the perpetual inventory method

(PIM) this might be represented by:

t

= N

t

(1

δ

) R

t−1

(3)

R +−

R

6

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

= PnN

= ΣPxX(N)

+

PrR(N)

= PyY

= ΣPxX(Y)

+

PrR(Y)

"Film Industry"

Note to Figure: To make the symmetry clear, a term for μ could also be included in the dow nstream. We assume that the dow nstream is

competitive, so μ=1, alw ays. Monopoly pow er does how ever exist in the upstream, due to the the ow nership of rights to a unique asset. So in the

upstream, μ>1.

Memo: PnN = Σ PrR / (1+r)t

Upstream Payments for rental of artistic originals

Costs of Labour, Capital & Intermediates in dow nstream

Dow nstream Payments for rental of artistic originals

e.g. Cinemas

Downstream:

Sales (Gross Output)

Upstream:

Creation of artistic original

e.g. Movie Production

plus

PnN = μ [ ΣPx(N)X(N) + PrR(N) ]

plus

Use of artistic original

Sales (Gross Output)

Costs of Labour, Capital & Intermediates in upstream

PyY = ΣPx(Y)X(Y) + PrR(Y)

}

Equation (2) says that the value of the asset must equal the discounted rental payments from

the users of the good.

Y

The final output sector, which uses the long-lived knowledge asset, produces output,

PY

.

Y LY KYMYRY

PY= PL + P K + P M + P R

(4)

LY

K Y

M Y

Where

PL

,

PK

and

PM

are the payments to labour, physical capital and materials in

R Y

the using sector, and

PR

are rental payments for using the IP created in the innovation

sector. These payments could be explicit rentals, or implicit in the case where the IP is owned

by the using firm. We assume that the final output sector is competitive and so there is no

mark-up, . A similar income identity for the materials sector completes the model.

An adjusted concept of market sector value-added, that accounts for the capitalisation of

intangible capital, consists of all the factor payments to labour and (tangible and intangible)

capital, with intermediate payments excluded.

Q L K R

PQ PL PK PR

(5)

= + +

The following diagram provides a representation of the model using the example of film originals,

but can be applied to any other form of IP.

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework. Upstream and Downstream in the Movie Industry

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

7

To summarise, in this model, UK investment in IP is the production of long-lived (i.e. with a

service life of at least one year) IP assets that are owned by UK residents. Consider then the

following distinctions:

– ‘UK IP production’ is all IP production that takes places in the UK, regardless of

ownership and duration of life;

– ‘UK IP investment’ is restricted to production of IP goods with a service life of more than

one year repeatedly used in the production of output (assets), that are owned

2

by a UK

resident;

– ‘UK IP consumption’ is the use of short or long-lived IP, by firms resident in the UK,

regardless of the residency of the owner;

– ‘Consumption of UK IP’ is the use of UK-owned short or long-lived IP, in all downstream

firms worldwide (not just those resident in the UK)

– ‘UK consumption of UK IP’ is use of short or long-lived UK IP in UK downstream firms

So, using our example of a film original, a feature movie produced in the UK but owned by an

American firm would be classed as UK production but not UK investment. The projection of

that same film in a UK cinema is ‘UK IP consumption’, but not ‘consumption of UK IP’.

The above framework also highlights the weaknesses in analysing UK IP investment using

official datasets. Suppose that we wish to measure the value of a TV or radio drama production

N

(

PN

). Our framework illustrates why this is hard to do from published industry data as

classified by the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC). Consider the SIC class “Television and

Radio Activities’. This does not distinguish between the production of programmes and their

broadcast. Moreover, production and broadcasting are often both undertaken by the same

organisation. So, both upstream and downstream activities are included in this SIC class.

Thus, a measure of sales for the whole industry includes: the downstream revenues earned by

Y

the broadcaster (

PY

), whether earned from long-lived IP assets or short-lived IP goods; all UK

IP production, including short-lived news or sports programmes, and also UK production of

assets owned in the Rest of the World (e.g. a US network funding and owning the rights to a

N

programme produced in the UK); as well as UK IP investment (

PN

).

In the case of Film the relationships between funding, ownership and performance are clear. A film produced in

the UK but with US funding and ownership is a US asset. With other knowledge assets, such as say R&D, these

relationships are less clear. R&D performed in the UK with overseas funding may or may not be owned in the UK.

Further, even if ownership resides overseas, some of the acquired knowledge remains in the UK. It is not

‘forgotten’.

2

8

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

Therefore we cannot use published SIC data to identify UK IP investment. Instead, we identify

UK production of IP assets owned in the UK. Continuing with the example of TV originals, we

use data from production companies or network production arms. Such data are reported for

ITV, BBC, Channel 4 in OFCOM reports. This allows us to make an estimate based on the

upstream input costs of asset creation, as in (1). However, we have to undertake a number of

adjustments. First, to identify investment, we must subtract the costs of production of short-

lived goods such as news and sports. Second, we must deduct the costs of production for

exported products (not UK-owned) and add in the value of imports (UK-owned). Third,

converting such costs into output values requires an estimate of the mark-up, µ, the value of

which is uncertain. Alternatively, if available, measures of investment can be estimated using

R

data on the income earned by that asset class (

PR

).

3

This latter approach is taken in the

estimation of investment in literary and music originals.

3. Measurement

Our measurement approach is designed to be consistent with the UK National Accounts and

therefore with official measures of output, income (accruing to labour and capital) and expenditure

(including consumption and investment). We start by estimating investment in knowledge assets

as identified by Corrado, Hulten et al. (2005) and applied in Goodridge, Haskel and Wallis (2012)

for the UK. We then adjust the official data from the National Accounts accurately to count

spending on knowledge assets with a shelf-life of more than a year as investment rather than

consumption, in a logically coherent framework that avoids double counting.

The categories of knowledge assets in our dataset are as featured in the NESTA Innovation

Index, and discussed in greater detail below. Included are new estimates of investment in

artistic originals, which have been revised in the national accounts, with the new estimates

based on our previous work funded by the UK IPO (Goodridge and Haskel 2011; Goodridge,

Haskel et al. 2012). As well as estimates of investment in knowledge by asset, we also present

estimates of investment protected by IPRs, including splits between registered rights (patents,

trademarks, registered design rights) and unregistered rights (copyright and unregistered design

rights).

In the steady-state, the value of investment is approximately equal to the value of capital compensation. 3

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

9

Below we provide a brief description of the methodologies and sources used to estimate

expenditure and investment on UK production of knowledge goods, by asset type. For a more

extensive description please consult past work such as Goodridge, Haskel and Wallis (2012).

Following Corrado, Hulten et al. (2005) we identify three broad groups of knowledge assets: i)

Computerised information; ii) Innovative property; iii) Economic competencies. The following

table sets out UK investment for each of these groups and the asset types within them. All

estimates presented are new to this report.

Table 1: UK Market Sector Investment; Tangible & Intangible, £bns nominal

Note to table. Data are investment figures, in £bns, current prices: italicised data are sub-totals for broader asset

definitions. MSGVA is presented with no intangibles capitalised; with only NA intangibles capitalized (software, mineral

exploration and artistic originals); and with all CHS intangibles capitalised. Market Sector refers to sectors A to K, MN,

R to U, thus excluding real estate. Estimates for intangibles are constructed as described below. Note estimates of

intangible investment do not equate to expenditure. Sub-totals might not add due to rounding. Source: ONS data for

tangibles, this paper for intangibles.

We note that these estimates for tangible investment are somewhat lower than we have

presented in the past. This is due to ONS revisions to current price investment in the 1990s and

2000s. ONS (2014) reports that overall estimates of current price GFCF for combined assets

has been revised down by about 3% on average over the period 1997 to 2010. Within that,

tangible investment has been revised down by some 15% on average over that period, while

intangible investment (referring only to intangibles already capitalised in the national accounts,

namely purchased and own-account software, artistic originals and mineral exploration) has

almost doubled in current prices. Changes to official estimates of intangible investment are due

to: a) revisions to estimates of investment in artistic originals, based on our previous work

10

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

(Goodridge and Haskel 2011; Goodridge, Haskel et al. 2012); and b) revisions to estimates of

investment in own-account software to better account for net operating surplus in own-account

K

software production (i.e. in terms of equation (1), to better account for

P K

N

).

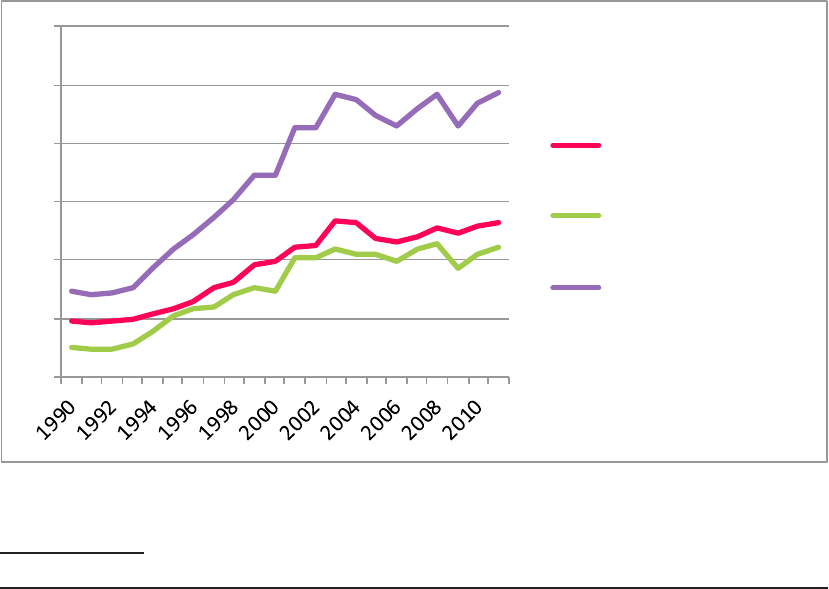

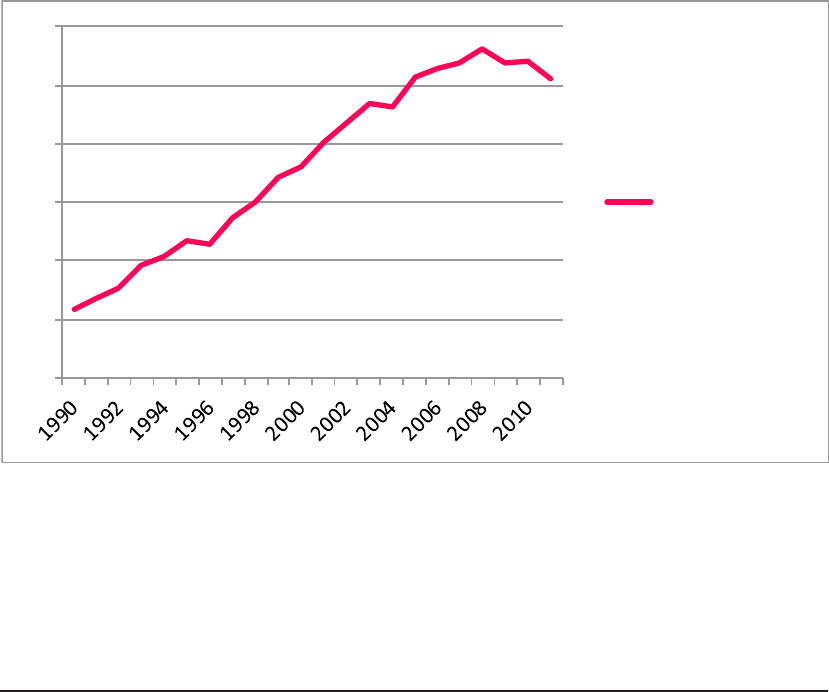

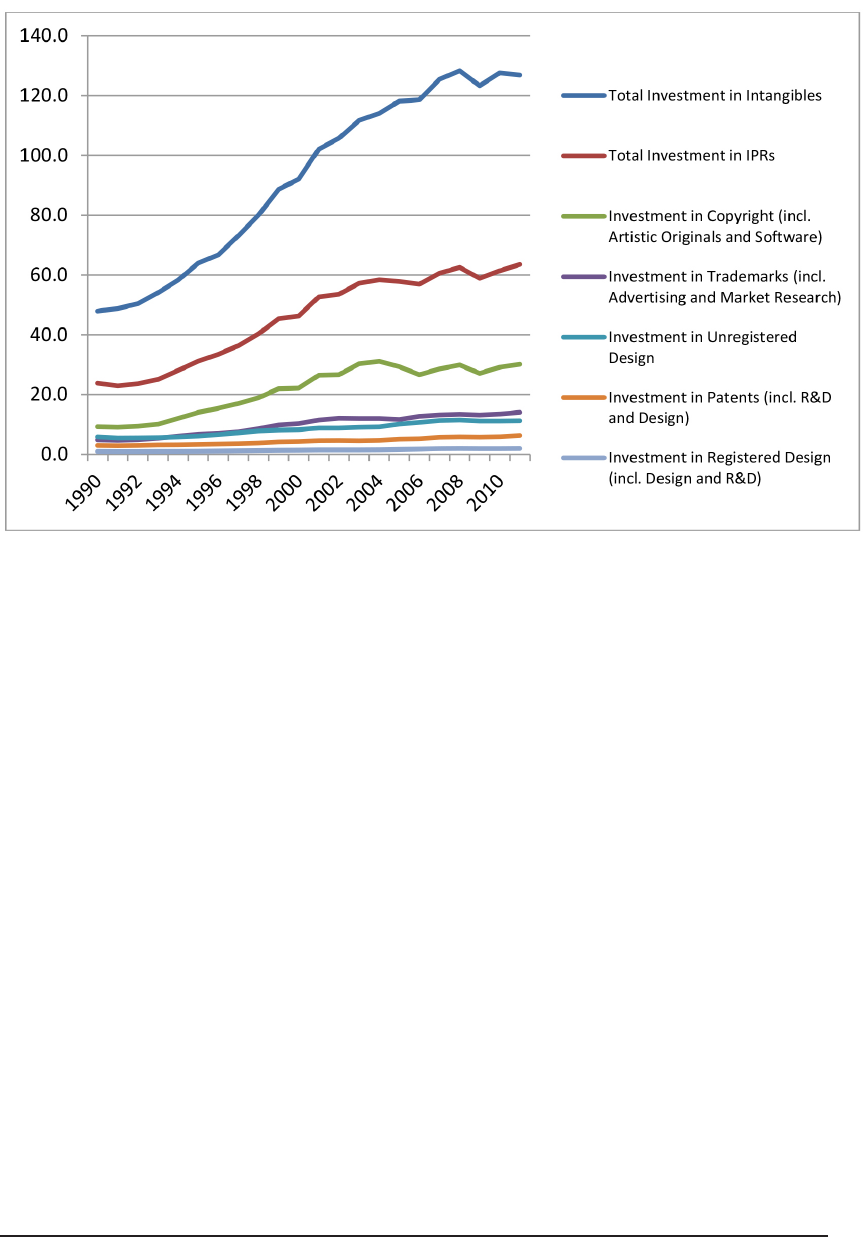

The following chart presents estimates of aggregate market sector investment in tangible and

intangible asset categories over the period 1990 to 2011. The recession is highlighted using the

blue bar.

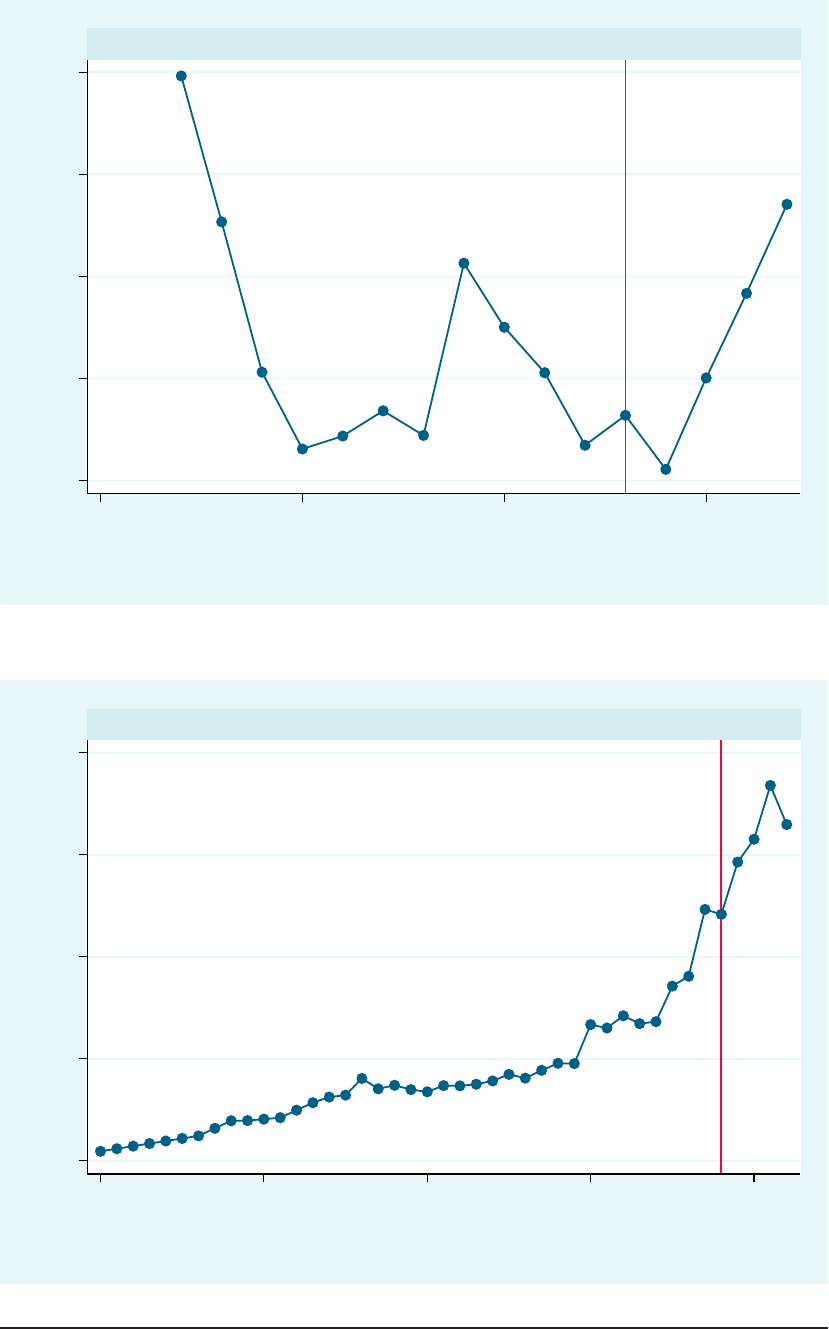

Figure 2. UK market sector investment in tangible and intangible assets, Nominal £bns

Source: ONS for tangible (downloaded 20th January 2014), this report for intangible

There are two main points to note from this chart. First, investment in intangibles has been

consistently higher than investment in tangibles since 1999. Second, although investment in

intangibles did decline during the recession it has since recovered. Nominal intangible investment

grew at 3.5% in 2010, although slightly declined by 0.6% in 2011. In contrast, tangible investment

collapsed in 2009 and has failed to recover since. Nominal tangible investment fell by 17.7% in

2009, grew by 2.5% in 2010 and fell again by 6.9% in 2011.

On tangible investment, these are the latest ONS data and reflect recent revisions to official

estimates of UK investment. They show that, in 2011, the level of nominal tangible investment

is below its level in 2000 (£88bn in 2011 compared to £94bn in 2000). Therefore, according to

the latest data, it seems that over the longest expansion in post-war economic history, nominal

tangible investment declined. The story of the 2000s is one of a slow decline in tangible

investment between 2000 and 2004, before a rise in the mid-2000s and then a collapse in the

later recession. Detailed data indicate that the rise in the mid-2000s is driven primarily by

investment in commercial property and intangibles (i.e. those intangibles already capitalised in

the national accounts, namely software, artistic originals and mineral exploration). Nominal

investment in plant (including ICT) is recorded at a lower level in 2011 than in 1998 (£36.1bn in

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

11

2011 compared to £45bn in 1998). This reflects ONS revisions to nominal investment which

primarily consist of a downward revision to investment in plant and an upward revision to investment

in intangibles. Note that insofar as plant investment includes computers, whose price is falling,

nominal investment might fall even if quantities rise

We now go on to discuss our measurement, and estimates of investment for each asset in more

detail.

3.1 Computerised Information and databases

As Figure 3 shows, software investment in 2011 was considerable at approximately £24bn,

comfortably exceeding Scientific R&D and also a broader definition of R&D that encompasses

R&D in social sciences and financial product innovation. Total Software investment comprises

both purchased and own-account

4

, and also computerised databases. Software is already

capitalised in the National Accounts, and so our source for computer software investment is

contained in the ONS work described by Chamberlin, Clayton et al. (2007). Purchased software

data are based on company investment surveys and own-account based on the wage bill of

employees in computer software occupations, adjusted downwards for the fraction of time spent

on creating new software (as opposed to, say routine maintenance) and then upwards for

associated overhead costs (a method we use for design below). The data, which run from 1997

to 2011, are updated data provided by ONS. The data are backcast further using previous

estimates of market sector software investment as reported in Goodridge, Haskel et al. (2012).

Estimates are presented below. We assume that 100% of investment in this asset category is

protected by copyright.

Figure 3. Software: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Own-account

Software

Purchased Software

Software Investment

(UK Market Sector)

Source: ONS

Own-account software is software developed by in-house employees 4

12

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

3.2 Scientific R&D

5

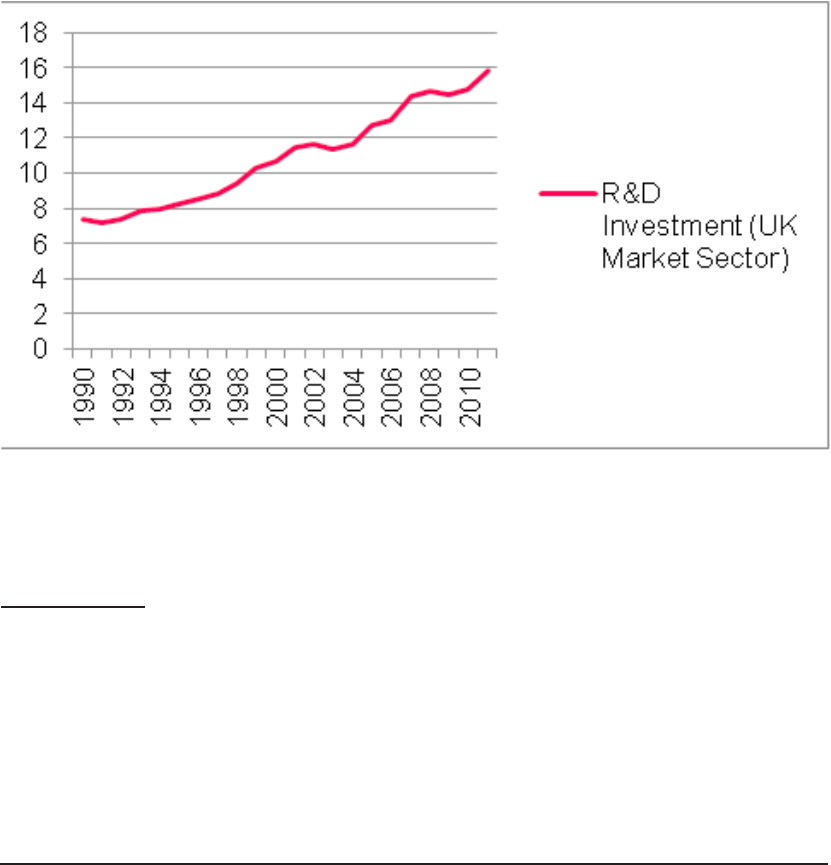

As shown in Figure 4, in 2011 investment in scientific R&D was approximately £16bn. For

business Scientific R&D we use expenditure data by industry derived from the Business

Enterprise R&D survey (BERD), which provides data back to 1981. To avoid double counting of

R&D and software investment, we subtract R&D spending in “computer and related activities”

(SIC 72) from R&D spending since this is already included in the software investment data. R&D

that takes place in R&D products is assumed to take place in the R&D services industry, and

that spend is allocated out using data on shares of R&D purchases in the Supply Use tables.

6

Since BERD also includes physical capital investments we convert those investments into a

capital compensation term, using the resulting physical capital stocks for the R&D sector and

the user cost relation

7

. Below we estimate that 38% of this investment is protected by patents

and 3% by registered design rights.

Figure 4. Scientific R&D: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

Source: ONS, BERD

5 Scientific R&D was capitalised in the 2008 revision to the System of National Accounts, and capitalisation in the

UK is due to be implemented in 2014.

6 The BERD data gives data on own-account spending. Spending is allocated to the industry within which the

product upon which firms are spending belongs. That is we assume that R&D on say, pharmaceutical products

takes place in the pharmaceutical industry. Spending on “R&D services” is allocated to business services. The

R&D services are sold to purchasing firms. We therefore allocate this spending out to the purchasing industries

using shares constructed from the supply use tables.

7 PK = PI (ρ+δ), where PK is the rental price of physical capital; PI is the asset price, ρ is the real rate of return and

δ is the depreciation rate.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

13

3.3 R&D in social sciences and humanities

In Figure 5 the estimate for R&D in social sciences and humanities is £0.9bn in 2011. R&D in

social sciences and humanities is estimated as twice the turnover of the industry “Research and

experimental development on social sciences and humanities” (SIC07 72.2), where the doubling

is assumed to capture own-account spending. Turnover data are taken from published data for

the Annual Business Survey (ABS) and previously the Annual Business Inquiry (ABI) and are

available for 1997 to 2011. Data are backcast using turnover data published in the Service

Sector review and Business Monitor. This is a small number and we suspect there is little

marginal benefit to improving its measurement. We assume that this investment is not protected

by formal IPRs. The series for non-scientific R&D is presented below.

Figure 5. Non-Scientific R&D: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

Non-scientific R&D

Investment (UK

Market Secto r)

Source: ONS, ABS, ABI

14

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

2

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

Investment in

1

Financial Product

0.8

Innovation (UK

0.6

Market Secto r)

0.4

0.2

0

3.4 Financial Product Innovation

In Figure 6, investment in Financial Product Innovation is estimated at £1.8bn in 2011. The

measurement methodology for New products development costs in the financial industry follows

that of own account software. Further details are in Haskel and Pesole (2010) but a brief outline

is as follows. First, we interviewed a number of financial firms to try to identify the job titles of

workers who were responsible for product development. Second, we compared these titles

with the available occupational and wage data from the Annual Survey on Hours and Earnings

(ASHE). The occupational classification most aligned with the job titles was ‘economists,

statisticians and researchers’. Third, we asked our interviewees how much time was spent by

these occupations on developing new products that would last more than a year. Some firms

based their estimates on time sheets that staff filled out. Fourth, we asked firms about the

associated overhead costs with such workers. Armed with these estimates, we went to the

occupational data in the ASHE and derived a time series of earnings for those particular

occupations in financial intermediation. Own-account investment in product development is

therefore the wage bill, times a mark-up for other costs (capital, overheads etc.), times the

fraction of time those occupations spend on building long-term projects. This provides data for

1997 to 2011. Data are backcast further using the growth rate of industry turnover. We assume

that such investment is not covered by formal IP rights.

Figure 6. Financial Product Development: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

Source: Own estimates, based on ASHE

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

15

3.5 Architectural and Engineering Design

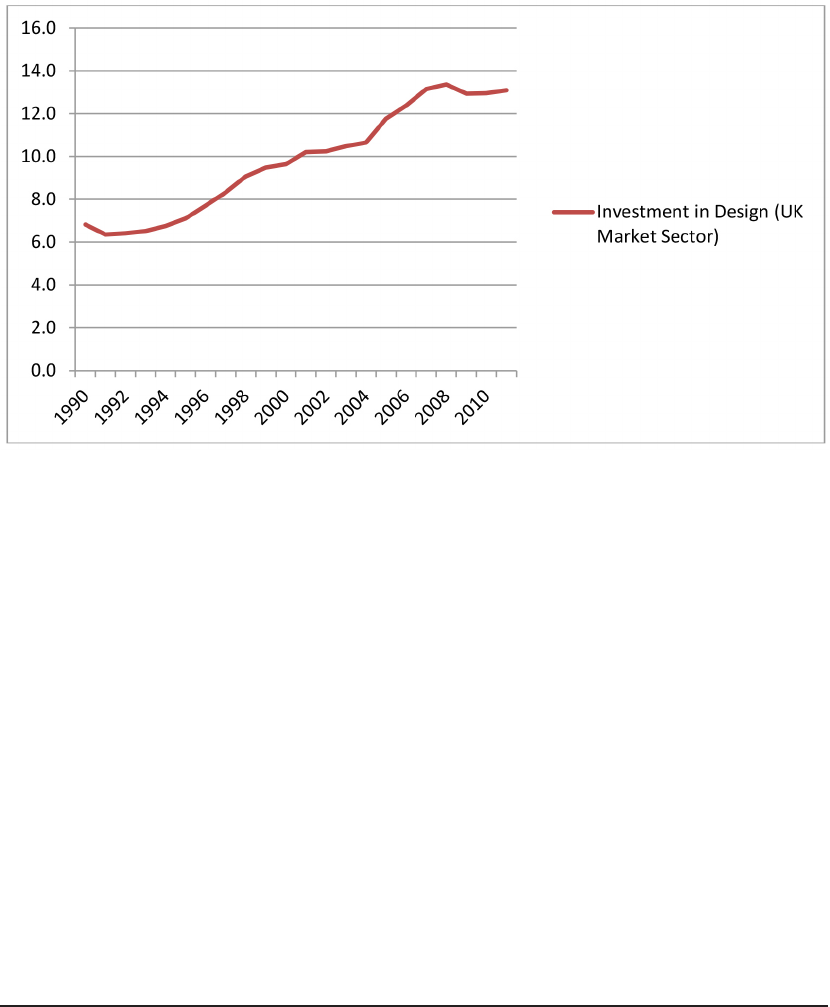

As shown in Figure 7, for 2011 we estimate investment in Design at £12.9bn in 2011. Purchased

data are taken from the Supply-Use Input Output (IO) tables. For own-account we use the own-

account software method. Full details are set out in Galindo-Rueda, Haskel et al. (2008).

In the case of purchased investments, as in Goodridge, Haskel et al. (2012), we have chosen to

exclude purchases of design by the industry itself (‘Professional, Scientific and Technical

Activities’, SIC 69t74), since some of these purchases will certainly include outsourcing and

subcontracting arrangements which would be double-counting. On own-account, the choice

of occupations and the time allocation are, as in financial services, taken from interviews with a

number of design firms. We focus on architectural, engineering and design (AED) activities,

including architects, engineers (excluding software) and general designers (graphic, product

and clothing designers). Interestingly, almost all of the design firms we interviewed have time

sheets for their employees which break out their time into administration, design and client

interaction/pitching for new business (almost all firms target, for example, that junior designers

spend little time on administration and senior more time on pitching). Thus, for professional

designers, we assigned 50% of their time to ‘long lived design’ and engineers only 10%, with

60% to the rest.

On engineers we note that here there is the potential for double-counting with R&D, since the

wages and salaries of engineers that conduct R&D will be reported in the BERD data. Not all

engineers will be involved in R&D however. This is another reason for choosing to only allocate

10% of the time of engineers to investment in design.

Further since some design expenditure/activity is short-lived rather than on the building of long-

lived assets, we further reduce the estimate by 50% to account for this. This factor is again

based on interviews conducted with design companies and the UK Design Council.

16

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

These methods provide estimates of investment for 1997 to 2011. Own-account estimates are

extended back further using data from the New Earnings Survey (NES) and purchased using

data from previous versions of the Supply Use Tables (back to 1992) and prior to that data on

the turnover of the design industry as published in the Business Monitor. Our series for UK

investment in architectural and engineering design is presented below. Of this estimate that

11% of this investment is protected by registered design rights, and 2% by patents. We assume

the remaining 87% is protected by unregistered design rights.

Figure 7. Architectural and Engineering Design: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

Source: Own estimates, based on ASHE and ONS Supply Use Tables

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

17

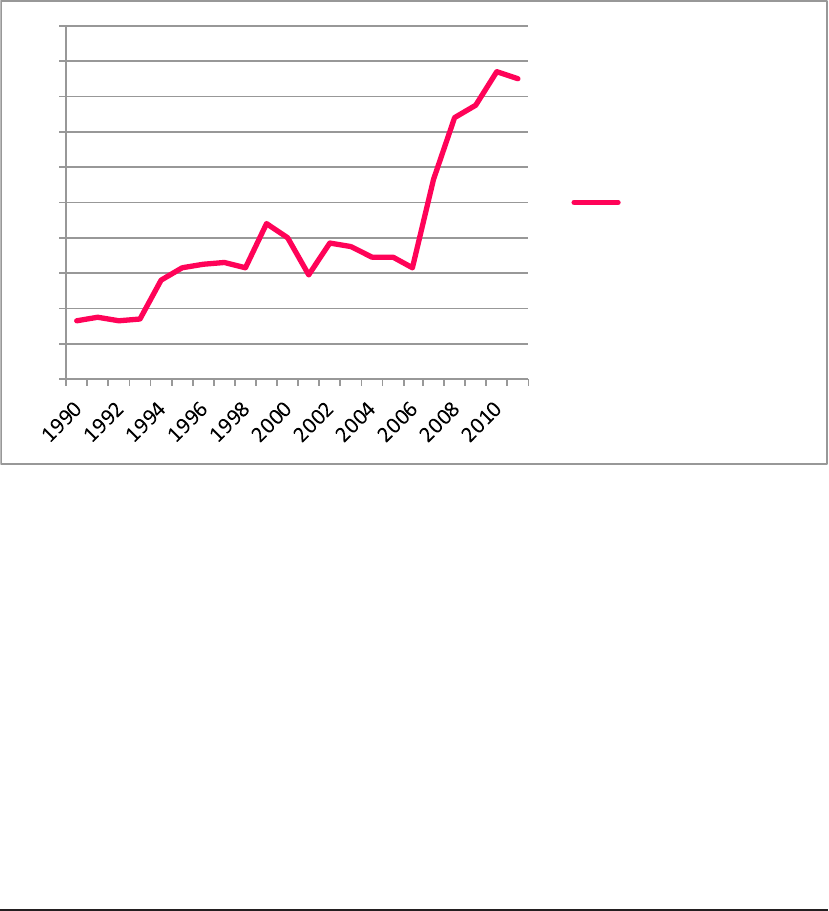

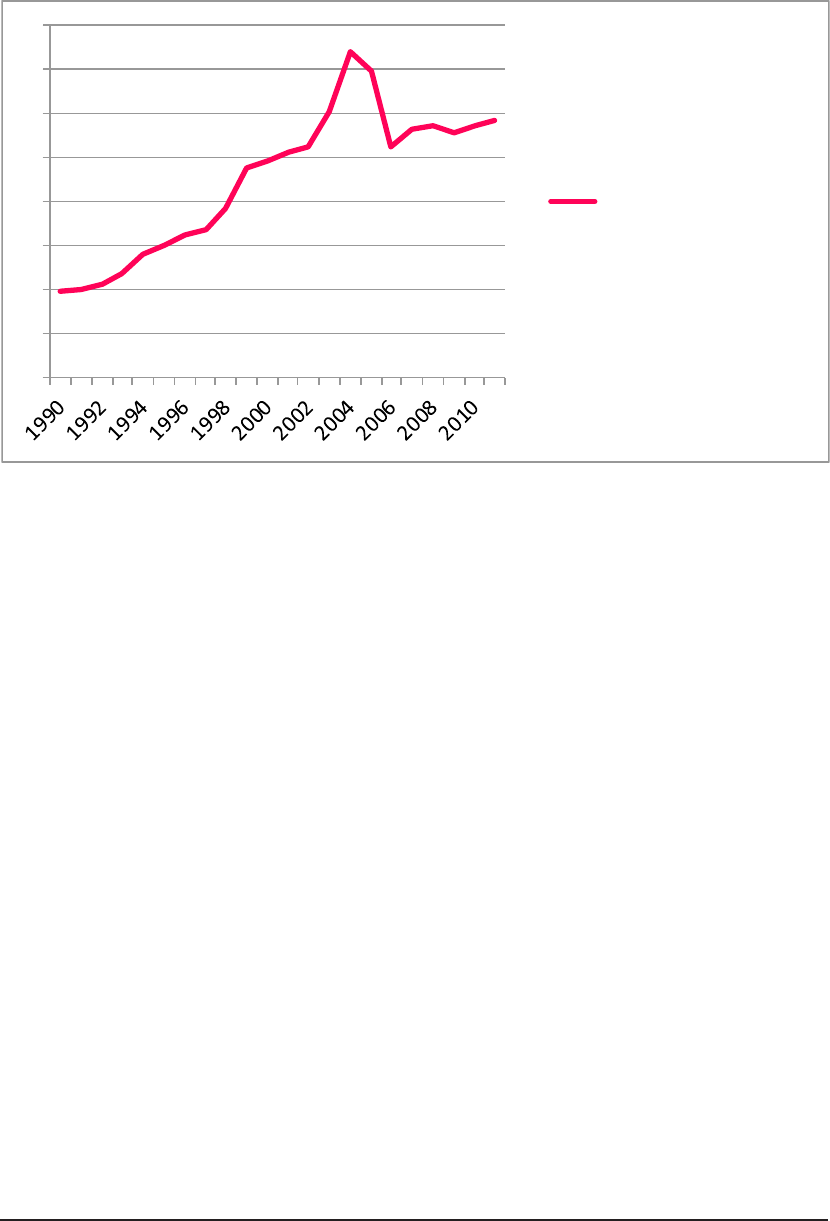

3.6 Artistic Originals

From Figure 8, in 2011 the estimate for investment in ‘Artistic Originals’ is £5.8bn. Artistic

Originals are already capitalised in the national accounts so we use those data. These estimates

are revised from past estimates, using new methods and data, based on our previous work

funded by the IPO (Goodridge and Haskel 2011; Goodridge, Haskel et al. 2012). We briefly

describe the data and methods used below. The estimates incorporate measures of UK

investment in: Film; TV & Radio; Music; Books; and Miscellaneous Art.

Estimates for investment in film originals are built bottom-up using data on budgets for UK

productions using a microdata set of all UK films produced since 1991. The dataset includes

information on co-producing partner countries and indicators on majority and minority funding.

We use such information to construct UK ownership shares for each individual film, providing us

with an estimate of investment in each UK-owned film original. Estimates for television and

radio are based on data for production costs for UK broadcasters, as published in OFCOM

Annual Reports, excluding expenditure on short-lived genres or formats such as ‘News’ or

‘Current Affairs’. Estimates for investment in literary originals are calculated using measures of

the capital compensation that flows to the owners of rights (namely publishing houses and

authors). Under the assumption of steady-state conditions, such compensation can be used

as a proxy for investment. Similarly, estimates for investment in recorded originals (music) are

also calculated using an income-based approach, with the data on income incorporating the

revenues earned by the owners of rights through recording sales, royalties distributed by the

music collecting societies, and revenues earned from live performance. For other forms of art

that meet the criteria for artistic originals (photography/images, choreographed routines, fine art

etc.), estimates are produced using data on the labour costs of relevant occupations as reported

in ASHE, and reduced by 50% to account for the possibility of such professions earning a

proportion of their income from other sources.

The official data for investment in Artistic Originals run from 1997 to 2011. We extend the

estimates back further using a combination of our own estimates (Goodridge and Haskel 2011;

Goodridge, Haskel et al. 2012) and the old national accounts estimates from prior to the revision.

The series for investment in this asset category is presented below.

8

One of the criteria for

identifying artistic originals is that they are covered by copyright. We therefore assume that

100% of investment in this asset category is protected by copyright.

We note the unusual spike in the series in the mid-2000s which we intend to investigate further. 8

18

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

Figure 8. Artistic Originals: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Investment in Artistic

Originals (UK Market

Sector)

Source: ONS, based on Goodridge and Haskel (2011) and Goodridge, Haskel et al. (2012).

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

19

3.7 Mineral Exploration

As shown in Figure 9, in 2011 investment in Mineral Exploration was £0.8bn. Like computerised

information and artistic originals, mineral exploration is already capitalised in the National

Accounts and the data here are simply data for Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) from the

ONS, valued based on “payments made to contractors or costs incurred on own account. The

costs of past exploration, not yet written-off, are re-valued (which in this case may well reduce

the value). This expenditure covers the costs of drilling and related activities such as surveys. It

is included in GFCF whether or not the exploration is successful.” (ONS 1998). These data run

from 1997 to 2011. They are extended back further using data from past releases of the

national accounts.

Figure 9. Mineral Exploration: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

Investment in Mineral

Exploration (UK

Market Secto r)

Source: ONS

20

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

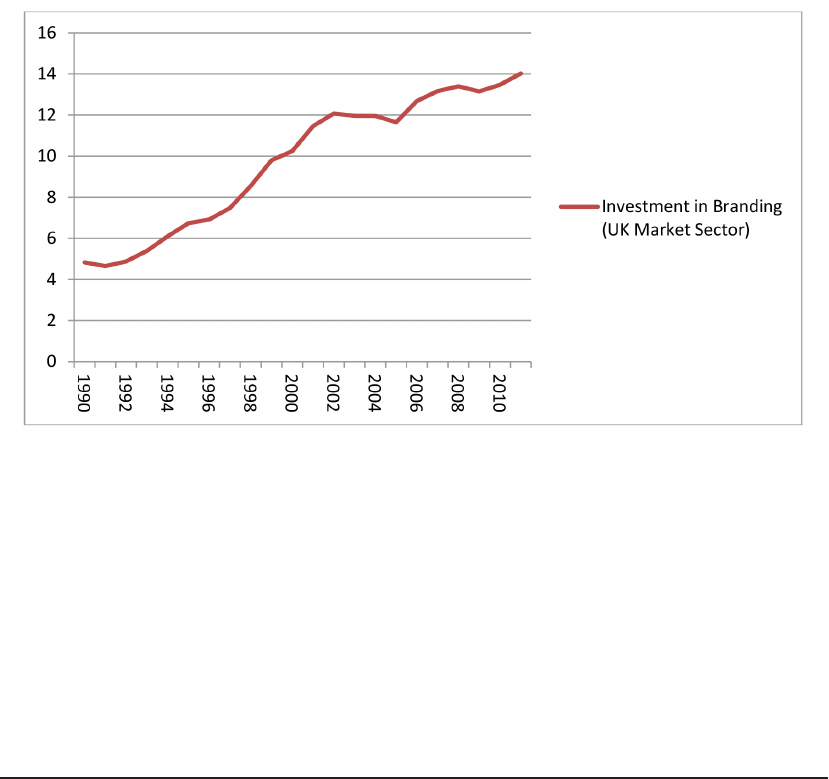

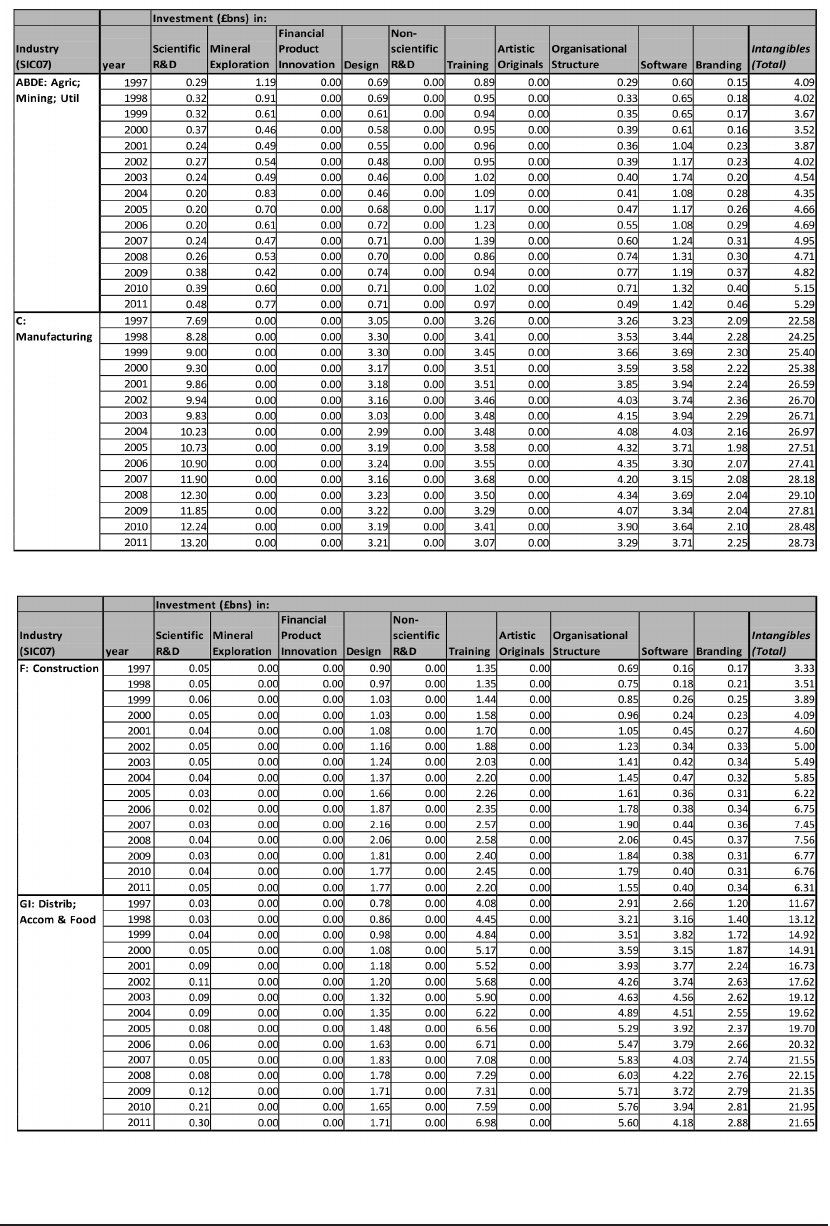

3.8 Branding: Advertising and Market Research

As shown in Figure 10, in 2011 we estimate total investment in Branding to have been around

£14bn. Of this, advertising made up £10.3bn, and market research £3.7bn. Each category is

estimated using data on purchases from the Supply Use Tables (product group 73: Advertising

and market research services) across all industries. As with design, we exclude purchases

made by the industry itself (SIC 69t74, Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities) since

some of these purchases include outsourcing and subcontracting arrangements which would

be double counting. Advertising and Market research are split using data from the ABS and

estimates for market research are further doubled to allow for own-account expenditure. As

with design, not all expenditure goes toward the building of reputational assets, since some is

short-lived. To account for this we take 60% of the expenditure estimates and assume that

proportion represents investment. These data are available from 1997 to 2011. Data are

extended back further using previous estimates constructed from past releases of the Supply

Use Tables. Our series for investment in Branding is presented on the following page.

Figure 10. Branding: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

Source: Own estimates based on ONS Supply Use Tables

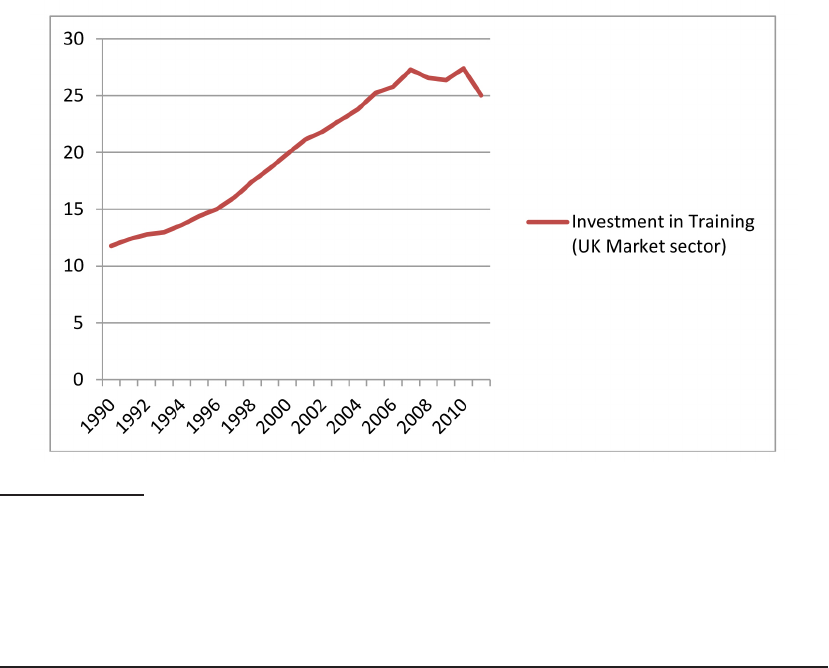

3.9 Firm-specific human capital (Training)

From Figure 11, our estimate of investment in Training is £25bn in 2011. Firm specific human

capital - training provided by firms - was estimated using cross sections from the National

Employer Skills Survey for 2007 and 2009.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

21

In previous estimates published in January 2014

9

(Goodridge, Haskel et al. 2014a

10

; Goodridge,

Haskel et al. 2014b

11

), estimates for investment in training included expenditures on the provision

of ‘Health & Safety’ and ‘Induction’ training. In these latest estimates (from Goodridge, Haskel

et al. (2014c

12

)), and consistent with past work (see Goodridge, Haskel et al. (2012)), we use

estimates from the National Employer Skills Survey (NESS) on what proportion of training spend

is on Health and Safety and Induction training and make an adjustment on that basis.

In the production industries, Health & Safety and Induction training is estimated at between 30

and 40% of total spend. Since it seems reasonable that Health and Safety training may have

more impact on firm productivity in the production industries compared to say Business

Services, and that Induction training in production may be more likely to include training on job-

specific skills, we decided to include this component for production but exclude it in the service

sector. As a result, estimated investment in training and hence total intangibles is lower than

published in either Goodridge, Haskel et al. (2014a) or Goodridge, Haskel et al. (2014b). Whilst

this subtraction lowers the level of training spending, it turns out to have little impact on the

estimated contribution of training to growth.

We also have data for 1988 from an unpublished paper by John Barber. We thus backcast the

series using the EU KLEMS

13

wage bill time series benchmarking the data to three cross

sections, and extend the series forward with ONS compensation of employees. Our series for

investment in Training is presented on the following page.

Figure 11. Training: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

Source: Own estimates based on NESS

9

10

11

12

13

Goodridge P, J Haskel, et al (2012). – “UK innovation Index productivity and growth in UK Industries

Goodridge P, J Haskel, et al (2014a). – “Estimating UK investment in intangible assets” Preliminary report for

NESTA”

Goodridge P, J Haskel, et al (2014b). – “Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property

Rights” Report for the UK Intellectual Property Office.

Goodridge P, J Haskel, et al (2014c). – “UK innovation Index 2014. “NESTA Working paper No.14/07

http://www.euklems.net/project_site.html

22

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

3.10 Organisational Structure

As shown in Figure 12, for 2011 we estimate investment in organisational structure at £25.5bn.

Our data on investment in organisational structure relies on purchased management consulting,

on which we have consulted the Management Consultancy Association (MCA), and own-

account time-spend, as before. On purchased, the MCA state that they represent 70% of the

industry. We therefore apply an upward adjustment to account for the remainder of the industry.

We have MCA data for the years 2002-05 and 2009-10. Estimates for other years are

interpolated and extrapolated using data on the turnover of the management consulting industry

from the ONS ABS and its predecessors. We also assume that not all purchased organisational

knowledge represents investment. Therefore 20% of purchased consultancy is removed from

the investment figure, on the basis that not all of the knowledge acquired is long-lived capital.

The method for own-account relies on identifying managers by occupation. Then using ASHE,

we take 20% of the managerial wagebill and assume that covers the own-account costs of

investments in the improvement of organisational processes.

Our own-account estimates run from 1997 to 2011. They are backcast further using data from

the NES. Our series for organisational investment is shown below. We assume that none of

these investments are protected by formal IPRs.

Figure 12. Organisational Structure: UK Investment, Nominal £bns

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Organisational

Investment (UK

Market Secto r)

Source: Own estimates based on data from the MCA and ASHE

All the above estimates are presented at the aggregate market sector level. Appendix 1 presents

estimates of intangible investment at the industry-level.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

23

4. Estimating the proportions

of knowledge investment

protected by IPRs

In measuring investment in assets protected by different types of IPRs, we also need to estimate

what proportion of investment is protected by IPRs. In this section we discuss our methods to

do that.

IPRs can be split into two broad groups: registered and unregistered rights. The first requires

formal application from innovators, the second are automatic and invoked by the innovator

when necessary. Table 2 summarises the IP rights considered in this report, how they fit into

each of these groups and previews our findings of what proportion of investment is protected

by IPRs (by asset type).

Table 2: Registered and Unregistered Rights; % of investment protected by IPRs

Registered

Unregistered

Design

Unregistered

% of investment

Asset \ IPR Patents Trademarks

Registration

Copyright

Design rights

protected by IPRs

Artistic Originals 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 100%

Software 0% 0% 0% 100% 0% 100%

Branding 0% 100% 0% 0% 0% 100%

Scientific R&D 38% 0% 3% 0% 0% 41%

Design 2% 0% 11% 0% 87% 100%

Note to table: estimates for percentage protected by IPRs based on this report. Note that shares of investment

protected do not equate to shares of expenditure protected.

First consider ‘Artistic Originals’. One of the criteria set out by Eurostat for classification as an

artistic original is that it must be covered by copyright. Therefore we consider our estimates of

investment in these assets to all fall within the category of ‘investment in copyrights’. Regarding

software, since all copyrighted works are recognised automatically when asserted by the owner,

we classify all investment in software (own-account and purchased) as ‘investment in copyrights’,

alongside investment in artistic originals.

For Branding, we also estimate that 100% of our measure of investment is protected by

Trademarks. Our reasoning is as follows. We recognise that not all expenditure on advertising

and market research constitutes investment. Based on industry discussions we estimate

investment in brands as 60% of expenditure on advertising and market research. In doing so,

we effectively remove all short-lived expenditure. Since the remaining investment is by definition

long-lived, we allocate all of that to our category ‘investment in trademarks’.

24

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

The remaining forms of intangible investment that can be protected by formal IPRs are Scientific

R&D and Design, each of which can be protected by either patents or design registration. We

estimate the proportions of these assets protected by these mechanisms below, using the

Community Innovation Survey (CIS) and econometric analysis. On R&D, we estimate that 38%

of R&D is protected by patents and 3% by registered design rights. On Design, we estimate

that 11% is protected by registered design rights and 2% by patents. Since ‘unregistered

design rights’ are automatic, we allocate the remaining 87% of investment to this IPR category.

We summarise our method and results below. We note that results in the wider literature are

supportive of these findings.

4.1. Allocating IP protection to investment

To estimate the fraction of investment protected by IPRs we may proceed via a) a questionnaire

or b) an econometric approach.

a) Questionnaire

There is a small body of work that attempts to ask what type of protection methods are used by

firms. First, in US work a minority of firms report using formal IP protection methods, and

instead typically report the use of first-mover advantages, secrecy or no formal protection at all.

Cohen, Nelson et al. (2000) asked firms whether they introduced a process and/or product

innovation and which IP protection mechanism they considered effective. In a sample of 1,065

American research laboratories in manufacturing, 1991-93, patents were considered effective

in 34% of product innovations and for 23% of process innovations. Patents were considered

most effective in pharmaceuticals (50%) and medical equipment (55%).

Second, in Europe, Arundel (2001) studies the question using the 1993 CIS for innovative

manufacturing firms in Norway, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark,

and Ireland. He presents the percentage of the 2,848 R&D performing firms who give the

highest rating to lead time, secrecy, complexity, patents and design registration. Patents score

11.2% and 7.3% for product and process innovations.

Third, Haskel and Pesole (2011) use the CIS to estimate how many firms report using design

rights. They find that 15% of firms report registering a design and that this is in line with other

studies.

Fourth, Farooqui, Goodridge and Haskel (2011) use data from the UK CIS. In a section

“Protection of Innovation” firms are asked to report the relative importance (no, low, medium

and high) of eight different protection mechanisms:

1. Design Registration

2. Trademarks

3. Patents

4. Copyright

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

25

5. Confidentiality Agreements

6. Secrecy

7. Complexity of Design

8. Lead time advantage over competitors

They found that the majority (52%) of firms report using none of these mechanisms, and those

that do use a combination of them. They also found that those who do report using such

mechanisms tend to be the largest spenders on R&D and other intangibles.

Table 2 from Farooqui, Goodridge and Haskel (2011) is reproduced below. It shows that, in

manufacturing for instance, only 31% of firms report using patents but these firms also

conducted 94% of industry expenditure on R&D and 81% of industry expenditure on Design.

Similarly, in manufacturing, only 31% of firms report using design registration but conducted

49% of design expenditure and 82% of R&D. Similar patterns exist for other industries. In

general those authors find that while attitudinal responses show a preference for informal IP

mechanisms, the R&D spending relative to sales profile is skewed towards those firms that

prefer formal IP mechanisms.

Table 3: Reported importance of IP methods, by industry

Industry Agric, Fish, Mining Manufacturing Gas Elect Water Construction

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

367 84209 6492 12819 4479866 760295 104 11262 910 3517 57174 99812

% % % % % % % % % % % %

Firms using Patents 17 94 81 31 94 81 15 2 91 9 71 90

Firms using

Trademarks

19 86 66 35 92 80 17 89 94 13 80 89

Firms using Design 14 89 34 31 82 49 16 1 40 11 73 34

Firms using

Copyrights

13 92 32 30 90 50 24 91 49 11 71 33

Industry Distbn, retails, hotels, restu Financial intermed Business Service Other

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

Firms R&D

spend

(£'000s)

Design

spend

(£'000s)

11245 362422 130779 1533 130314 37942 8815 2095602 310993 132 3336 239

% % % % % % % % % % % %

Firms using Patents 13 72 45 11 52 20 17 89 91 14 5 24

Firms using

Trademarks

20 70 84 20 62 50 23 85 81 21 19 25

Firms using Design 15 66 38 14 53 8 18 79 40 15 7 11

Firms using

Copyrights

15 65 25 20 66 36 25 85 49 33 26 36

Note to table. Each cell shows, by industry, the percentage of firms using each protection type and the fraction of all

spending on R&D and design in that industry that those using firms account for. Note that firms can report that they

use more than one protection type. Source: CIS.

26

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

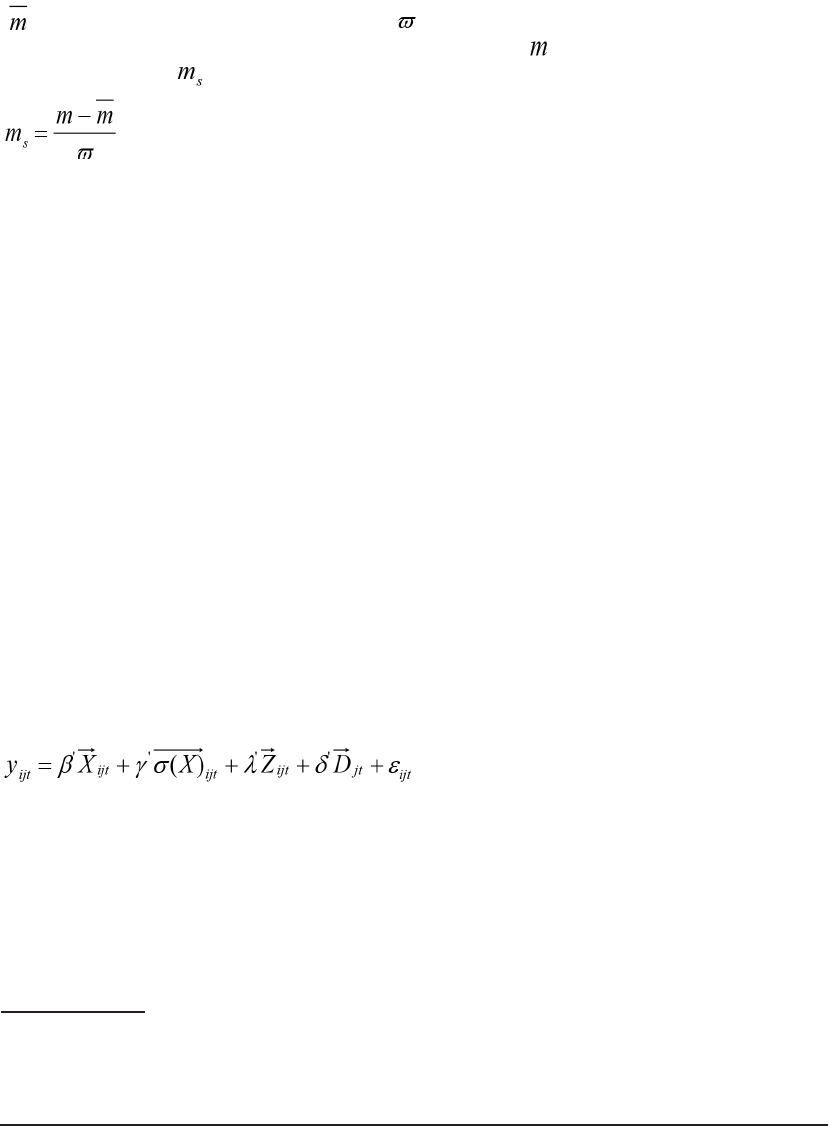

b) Econometric estimation

To examine this for the UK, we use the fifth wave of the CIS (2004-2006). In the econometric

approach there are two preliminary issues to be dealt with. First, firms use multiple protection

methods. Second, the methods are subject to firm specific response bias. Therefore, in order

to isolate response specific variation, we compute the mean importance across all 8 mechanisms

( ), and the associated standard deviation ( ). All responses are then adjusted by the mean

and standard deviation to correct for the response bias. Let denote the score of a particular

mechanism and let denote its standardized value then:

(6)

For example, let’s say a firm reports an importance vector of (0, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3) for design

registration, trademarks, patents, copyright, confidentiality, secrecy, complexity and lead-time

respectively. The firm-specific mean is (0+1+2+1+2+2+3+3)/8=1.75, and the standard

deviation is 1.035. The above transformation then returns an importance of (1-1.75)/1.035 =

-0.72 for trademark and copyright, equivalently it returns an importance of (3-1.75)/1.035 =

1.2 for complexity and lead-time.

The standardization assumes that each individual response is taken from the same underlying

normal distribution. It therefore endows each individual response the same measurement unit

and amplifies the importance of those responses that are further away from the firm bias

14

. In

doing so the transformation signifies relative importance to the others.

Consider now the allocation of spend. Each firm reports R&D and other intangible spend and

the use of possible multiple methods of IP protection. Hence the question is: how do we allocate

the spend in each firm to its reported IP?

Consider R&D. How much R&D is: (a) protected by patents; and (b) protected by registered

design rights. To answer this we conduct a firm-level regression analysis that correlates the R&D

to sales ratio with the different IP types. While the regression analysis does not make any causal

assumptions, it can be regarded as a reduced form description of the sensitivity of R&D/sales

to reported use of IP. The regression takes the following form:

(7)

14 We note that this transformation (a) requires the mean for each firm of the transformed variable is 0 and (b)

transforms firm level responses to missing if there is no variation in returns i.e. all importance rankings are firm

specific but not response specific.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

27

23

Where on the left hand side we use R&D as a % of sales. On the right hand side, the vector

ijt

X

represents firm level IP use intensity and contains standardized responses for the individual IP

mechanisms. The firm level mean and standard deviation of these responses is captured in the vector

()

ijt

X

σ

. The IP use vector can be expanded out as:

0 1 2 3

4 5 6 7

ijt

X Design Trademarks Pat ents Copyright

Confidentiality Secrecy Complexity Lead Time

αβ β β β

β β β β

= + + + +

+ + + +

(8)

Where

α

captures the R&D/Sales intensity of those firms that do not rely on any IP mechanism,

2

β

captures the elasticity of R&D intensity to patent use holding all other forms of IP use constant, and

0

β

the elasticity of R&D intensity to the use of design registration holding all other forms constant.

The

β

coefficients are not structural parameters and therefore do not represent a causal change in

demand for R&D intensity i.e. we are not saying that firms first decide on IP use and then how much

to spend on R&D. Rather, they are the reduced form correlations and can be regarded as a summary

of the various elasticities. As long as the use/importance of each IP mechanism is measured in the

same units, we can calculate the ratio

which would give the share of spending that would be

accounted for by firms using IP type i as protection, as a share of total spending by those firms using

any form of protection.

As implied by (7) we also include a number of control variables. As noted we include the firm level

mean and standard deviation of IP responses. We also include the % of employees with a degree in

science or engineering, the log of employment and industry dummies.

The R&D relationship is analysed using standard OLS. For Design, we note that questions on design

expenditure are less well answered on the CIS (Awano, Franklin, Haskel et al (2010a)). There are

also many instances where firms respond positively to the question of whether they undertake activity

but the expenditure estimate is zero or missing. Therefore we use the binary question on design

activity and so employ a probit procedure. Since the questions on R&D expenditure appear to be

better answered, we have more confidence in using the expenditure data in the case of R&D.

The results are presented below in Table 4. Column 1 presents a probit regression for design, where

the left-hand side variable is a binary yes/no response and the right hand side includes demeaned

responses for each IP protection mechanism as described above. Also included in the regression, but

Where on the left hand side we use R&D as a % of sales. On the right hand side, the vector

X

ijt

represents firm level IP use intensity and contains standardized responses for the individual IP

mechanisms. The firm level mean and standard deviation of these responses is captured in the

vector

σ

()

ijt

. The IP use vector can be expanded out as:

X

X

ijt

αβ

Design +

β

Trademarks +

β

Patents +

β

Copyright

(8)

=+

0 1 2 3

+

β

Confidentiality +

β

Secrecy +

β

Complexity +

β

Lead Time

4 5 6 7

Where

α

captures the R&D/Sales intensity of those firms that do not rely on any IP mechanism,

β

2

captures the elasticity of R&D intensity to patent use holding all other forms of IP use

constant, and

β

the elasticity of R&D intensity to the use of design registration holding all other

0

forms constant. The

β

coefficients are not structural parameters and therefore do not represent

a causal change in demand for R&D intensity i.e. we are not saying that firms first decide on IP

use and then how much to spend on R&D. Rather, they are the reduced form correlations and

can be regarded as a summary of the various elasticities. As long as the use/importance of

each IP mechanism is measured in the same units, we can calculate the ratio

7

which would

∑

=0

give the share of spending that would be accounted for by firms using IP type i as protection,

as a share of total spending by those firms using any form of protection.

As implied by (7) we also include a number of control variables. As noted we include the firm

level mean and standard deviation of IP responses. We also include the % of employees with a

degree in science or engineering, the log of employment and industry dummies.

The R&D relationship is analysed using standard OLS. For Design, we note that questions on

design expenditure are less well answered on the CIS (Awano, Franklin, Haskel et al (2010a)).

There are also many instances where firms respond positively to the question of whether they

undertake activity but the expenditure estimate is zero or missing. Therefore we use the binary

question on design activity and so employ a probit procedure. Since the questions on R&D

expenditure appear to be better answered, we have more confidence in using the expenditure

data in the case of R&D.

The results are presented below in Table 4. Column 1 presents a probit regression for design,

where the left-hand side variable is a binary yes/no response and the right hand side includes

demeaned responses for each IP protection mechanism as described above. Also included in

the regression, but not shown, are the control variables described above. Column 2 reports the

marginal effects from this regression. Column 3 presents the results of an OLS estimation,

where the left-hand side variable is R&D/Sales and the right hand side includes demeaned

responses on the importance of IP mechanisms and the control variables. In each regression,

in order to identify the idiosyncratic impact of the different mechanisms we assign one mechanism

as the reference category and constrain its impact to zero.

28

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

EQUATION VARIABLES

(1)

Design

(1/0)

(2)

Marg.

Effects of

Col (1)

(3)

R&D/Sales

design_yn Design

Trademarks

0.0549*

(0.0283)

0.0119

0.0190*

(0.00981)

0.00412

0.0368

(0.145)

Patents

(0.0263)

0.00958

(0.00910)

0.00332 0.415***

Confidentiality

Copyright

Complexity

LeadTime

(0.0294)

0.0250

(0.0297)

0.0619**

(0.0274)

0.247***

(0.0292)

0.0948***

(0.0102)

0.00867

(0.0103)

0.0214**

(0.00947)

0.0854***

(0.0101)

0.0328***

(0.146)

0.00889

(0.118)

0.160

(0.137)

0.343***

(0.122)

0.00972

SINGLE Secrecy

(0.0252) (0.00871) (0.111)

0.129

(0.1

18)

Observations 6,823 6,823 3,965

R-square

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

0.165

Sum of marginal effects: Σβi

% protected by Patents

% protected by Design rights

0.17471

1.9%

10.9%

1.10241

37.6%

3.3%

Table 4: Regression estimates of proportions of R&D and Design protected by IPRs

Note to table: Column 1 is a probit regression using a binary yes/no variable on whether firms conduct design as the

regressor. Column 2 reports the marginal effects for the regression in column 1. Column 3 reports an OLS regression

using the firm R&D/sales ratio as the regressor. Columns 1 and 3 include controls such as industry dummies, the mean

and standard deviation of responses on IP mechanisms, employment and the proportion of employees with a degree in

science or engineering.

Column 2 reports the marginal effects for the regression in Column 1. According to these

estimates, the most important IP protection mechanisms for firms conducting design are: 1)

Complexity; 2) Lead Time; 3) Copyright; 4) Design registration; in that order. We wish to

determine what proportion of design is protected by: a) registered design rights; and b) patents.

Taking the marginal effect for each of these mechanisms as the sum of all the marginal effects

we estimate that: 11% of design is protected by registered design rights; and 2% of design is

protected by patents. By assumption, the remainder of design (87%) is protected by unregistered

design rights.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

29

Column 3 presents our results for R&D, this time using R&D intensity as the dependent variable.

The results suggest that the most important protection mechanisms for R&D are: 1) Patents; 2)

Complexity; 3) Copyright; 4) Secrecy; and 5) Design Registration. Since the coefficient on each

mechanism provides an estimate of the marginal effect, taking the coefficient on patents and

design registration as a sum of all the coefficients, we estimate that: 38% of R&D is protected by

patents; and 3% of R&D is protected by registered design rights.

One might reasonably imagine that these effects vary by industry and hence we would wish to run

separate regressions for each industry. We are however limited in our ability to conduct a similar

regression exercise for each and every industry. On the one hand, most R&D activity is limited to

specific sectors. On the other hand, the CIS survey simply does not survey enough firms in very

detailed industries of interest, such as pharmaceuticals, and we are limited in our ability to exploit

firm level variations and draw statistically meaningful conclusions. In addition, disclosure concerns

dictate a certain degree of aggregation. With these trade-offs in mind, we only conduct our analysis

at the aggregate market sector level.

Of the remaining assets not discussed in this section, such as Training and Organisational Structure,

we assume that none of these investments are protected by formal IPRs. Of course certain

licensing rights apply to activities such as Mineral Exploration, but not IPRs which are our interest

in this report.

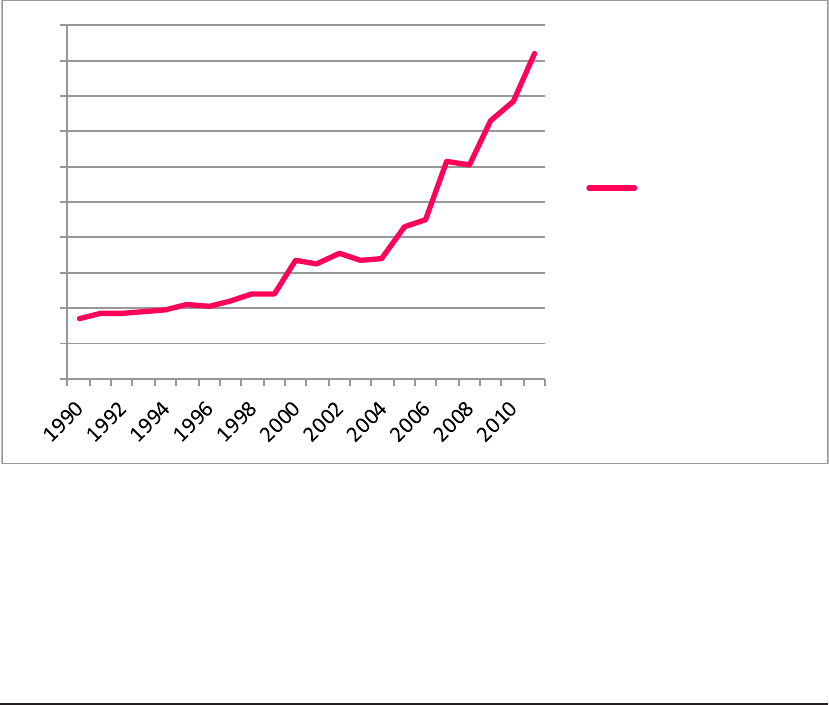

We now apply our estimates of what proportion of investment is protected by IPRs, to our dataset.

Results are presented below in Table 5. We estimate that almost half (48% in 2011) of UK

investment in intangibles is in assets protected by formal IPRs, amounting to £65.6bn in 2011. Of

that, almost half (46% in 2011) is in assets protected by copyright, namely software and artistic

originals. Of the remainder, trademarks and unregistered design rights each account for 21%,

patents for 10%, and registered design rights for 3%. A chart showing estimated investment in

each of the five types of IPR is presented below in Figure 13.

Table 5: UK Market Sector Investment in Intellectual Property Rights (Nominal, £bns)

1990 1995 2000 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Investment in Patents (incl. R&D and Design) 2.9 3.3 4.3 5.1 5.2 5.8 5.9 5.8 5.9 6.3

Investment in Copyright (incl. Artistic Originals and

Software)

9.2 14.0 22.1 29.3 26.7 28.6 29.9 27.0 29.1 30.1

Investment in Registered Design (incl. Design and R&D) 1.0 1.0 1.4 1.7 1.7 1.9 1.9 1.8 1.8 1.9

Investment in Unregistered Design 5.9 6.1 8.3 10.1 10.6 11.3 11.5 11.1 11.1 11.2

Investment in Trademarks (incl. Advertising and Market

Research)

4.8 6.7 10.2 11.7 12.7 13.2 13.4 13.1 13.5 14.0

Total Investment in IPRs 23.8 31.1 46.3 57.8 56.9 60.6 62.5 58.9 61.4 63.5

Total Investment in Intangibles 47.9 63.9 92.1 118.1 118.6 125.5 128.3 123.3 127.6 126.8

Note to table: Investment in patents estimated as 38% of investment in scientific R&D plus 2% of investment in design.

Investment in copyright estimated as 100% of investment in artistic originals and software. Investment in registered design

estimated as 11% of investment in design plus 3% of investment in scientific R&D. Investment in unregistered design

estimated at 87% of investment in design, that is, the remainder of design investment not allocated to patents or registered

design. Investment in trademarks estimated as 100% of investment in advertising and market research.

30

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

Figure 13. Total Investment in assets by IP coverage, Nominal £bns

Source: Own estimates, see note to Table 5.

In this report we have presented nominal measures of investment in intangible assets, and on

intangible assets protected by formal IPRs. Real, or volume, measures would require deflating

these estimates with an appropriate price index. In this context it is worth saying something about

real investment in R&D and therefore patented R&D. Here our estimate for investment in patented

R&D is £6.4bn in 2011, having risen from £2.9bn in 1990. The average rate of growth in nominal

patented R&D, over the period 1990 to 2011, is 3.7%. Applying an output price index such as a

GDP deflator, as is typical for R&D, rising at a rate of approximately 3 to 4% p.a., would imply that

there has been almost no rise in real R&D investment. However, recent studies suggest that the

implicit price of R&D may have been falling rapidly due to technological innovation in the R&D

upstream sector (Corrado, Goodridge and Haskel (2011)). Those authors estimate the price of R&D

in the UK to have fallen at an average rate of approximately -7.5% p.a. over the period 1985 to

2005. Applying this price index would therefore imply that real patented R&D investment has grown

at a rate of approximately 11% p.a. over the period considered here.

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

31

5. Conclusions

Applying the intangibles framework, as used in the NESTA Innovation Index, we find that total

UK market sector investment in intangible assets reached £126.8bn in 2011, compared

to £88bn of investment in tangible assets. We also note that since the recession of 2008-9,

intangible investment has recovered and grew in 2010-11. In contrast investment in tangible

assets has fallen. Of the £126.8bn invested in intangibles in 2011, we estimate that approximately

half (£63.5bn) was investment protected by formal IPRs (patents, copyright, registered design

rights, unregistered design rights or trademarks). Of investment protected by IPRs, the largest

component is investment in copyright, which stood at £30.1bn in 2011. Investment in

unregistered design rights and trademarks were £11.2bn and £14bn respectively in 2011,

investment in patents, £6.3bn, and investment in registered design rights, £1.9bn.

In forming these estimates we first identify investment in each intangible asset, as set out in

Corrado, Hulten et al. (2005). We then form estimates of how much investment in each asset

type is formally protected by IPRs. In doing so, we allow for the fact that both scientific R&D

and Architectural and Engineering Design can be protected by either patents or registered

design rights. We estimate that 38% of investment in scientific R&D is protected by patents and

3% by registered design rights. We also estimate that 11% of investment in Design is protected

by registered design rights and 2% by patents. The remainder of investment in Design is

assumed to be protected by unregistered design rights. We further assume that 100% of

investment in Artistic Originals and Software is protected by copyright, and that 100% of

investment in Advertising and Market Research is protected by Trademarks.

We emphasise that this work estimates investment in knowledge assets and the proportions of

that investment protected by formal IPRs. We take no stand on whether investment in knowledge

assets is higher or lower than it would have been were those assets not protected by IPRs. That

area requires further work. Whilst some evidence suggests that the ability to use IPRs increases

investment in innovation through the incentive of monopolist revenues, others suggest that the

same mechanism reduces innovation by removing the incentive to continually innovate.

Nevertheless, the scale of investment in IPR-protected assets is not fully appreciated. Investment

in IPRs is higher than that in commercial buildings and also higher than plant & machinery

(including ICT) and vehicles combined. The role of assets protected by IPRs, as drivers of

growth, deserve greater consideration in both measurement and policy.

32

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

References

Arundel, A. (2001). “The relative effectiveness of patents and secrecy for appropriation.”

Research Policy 30(4): 611-624.

Awano, G., M. Franklin, et al. (2010a). “Measuring investment in intangible assets in the UK:

results from a new survey.” Economic and Labour Market Review 4(7): 66-71.

Chamberlin, G., T. Clayton, et al. (2007). “New measures of UK private sector software

investment.” Economic and Labour Market Review 1(5): 17-28.

Cohen, W. M., R. R. Nelson, et al. (2000). Protecting their intellectual assets: Appropriability

conditions and why US manufacturing firms patent (or not), National Bureau of Economic

Research.

Corrado, C., P. Goodridge, et al. (2011). “Constructing a Price Deflator for R&D: Calculating the

Price of Knowledge Investments as a Residual.”

Corrado, C., C. Hulten, et al. (2005). Measuring capital and technology: an expanded framework.

C. Hulten, University of Chicago Press.

Farooqui, S., P. Goodridge, et al. (2011). “The Role of Intellectual Property Rights in the UK

Market Sector.”

Galindo-Rueda, F., J. Haskel, et al. (2008). How much does the UK employ, spend and invest

in design, CeRiBA Working paper, April.

Goodridge, P. and J. Haskel (2011). Film, Television & Radio, Books, Music and Art: UK

Investment in Artistic Originals, CERIBA working paper.

Goodridge, P., J. Haskel, et al. (2012). “Updating the value of UK copyright investment.”

Goodridge, P., J. Haskel, et al. (2012). “UK Innovation Index: productivity and growth in UK

industries.”

Haskel, J. and A. Pesole (2010). Productivity and Innovation in UK Financial Services: An

Intangible Assets Approach.

Haskel, J. and A. Pesole (2011). “Design services, design rights and design life-lengths in the

UK.”

OfficeforNationalStatistics “Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 1997-2011: Secure Data

Service Access [computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], April 2013.

SN:6689.”

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

33

OfficeforNationalStatistics “National Employers Skills Survey: Secure Data Service Access

[computer file]. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], June 2011. SN:6705.”

OfficeforNationalStatistics “UK Innovation Survey: Secure Data Service Access [computer file].

Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], August 2013. SN:6699.”

ONS (1998). “National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods.”

ONS (2014). “Multi-factor Productivity, Indicative Estimates to 2012.”

34

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

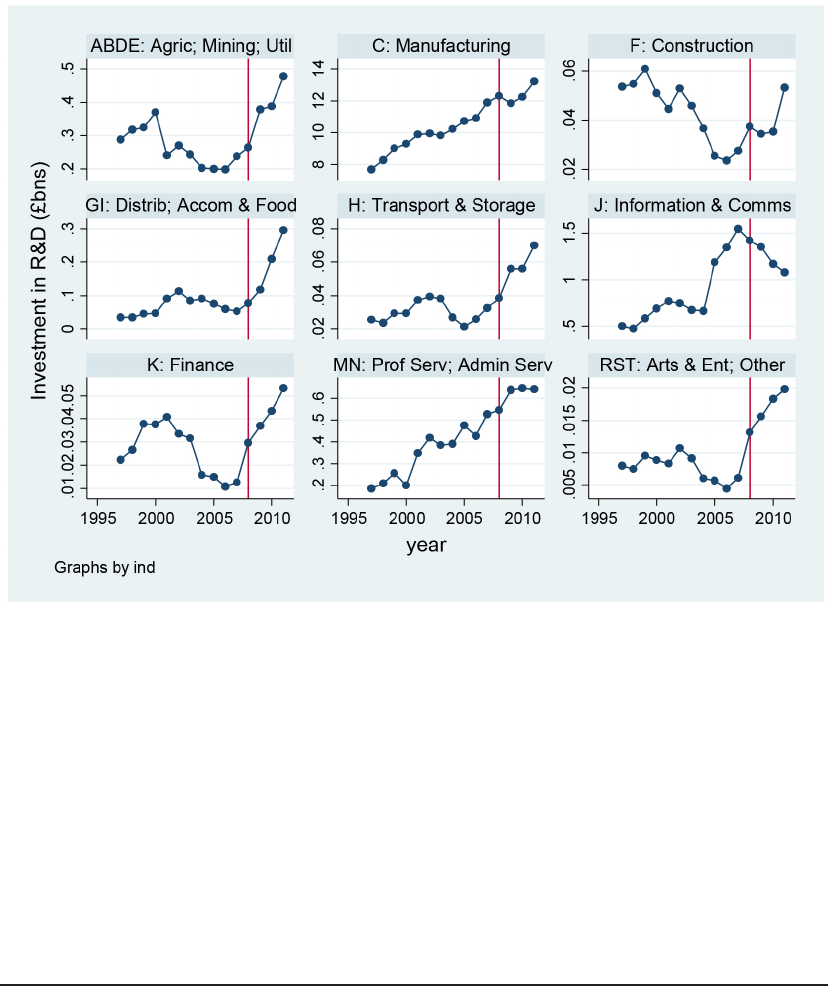

Appendix 1: Industry-level

Intangible Investment

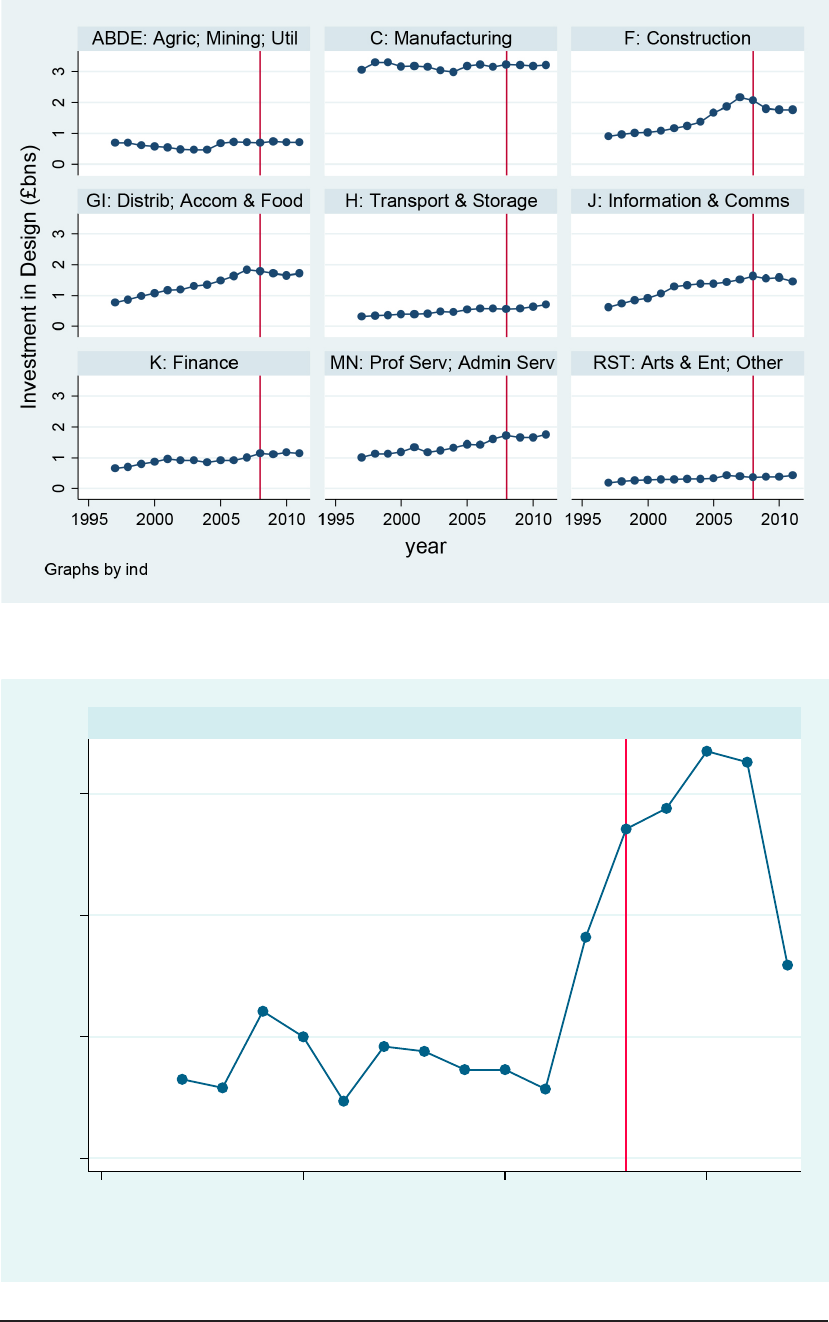

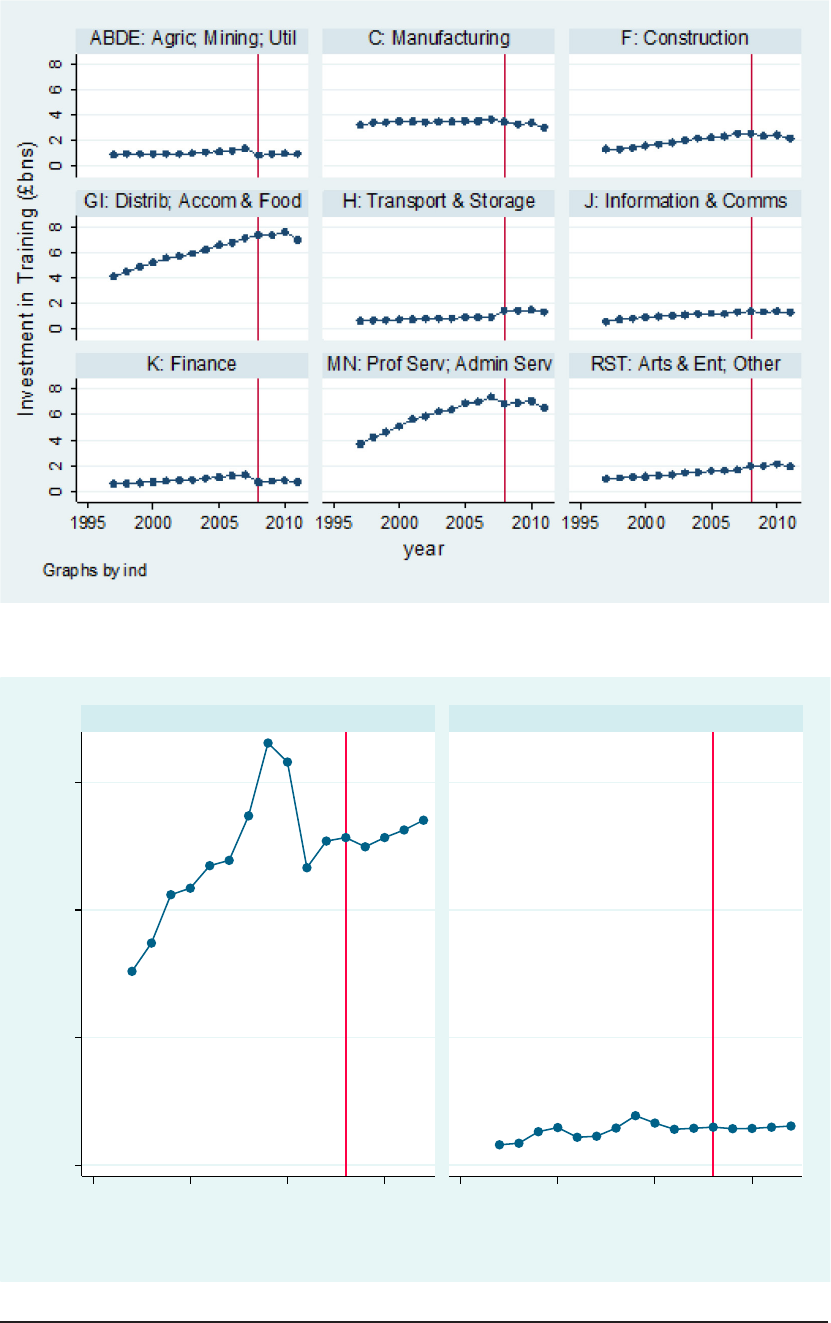

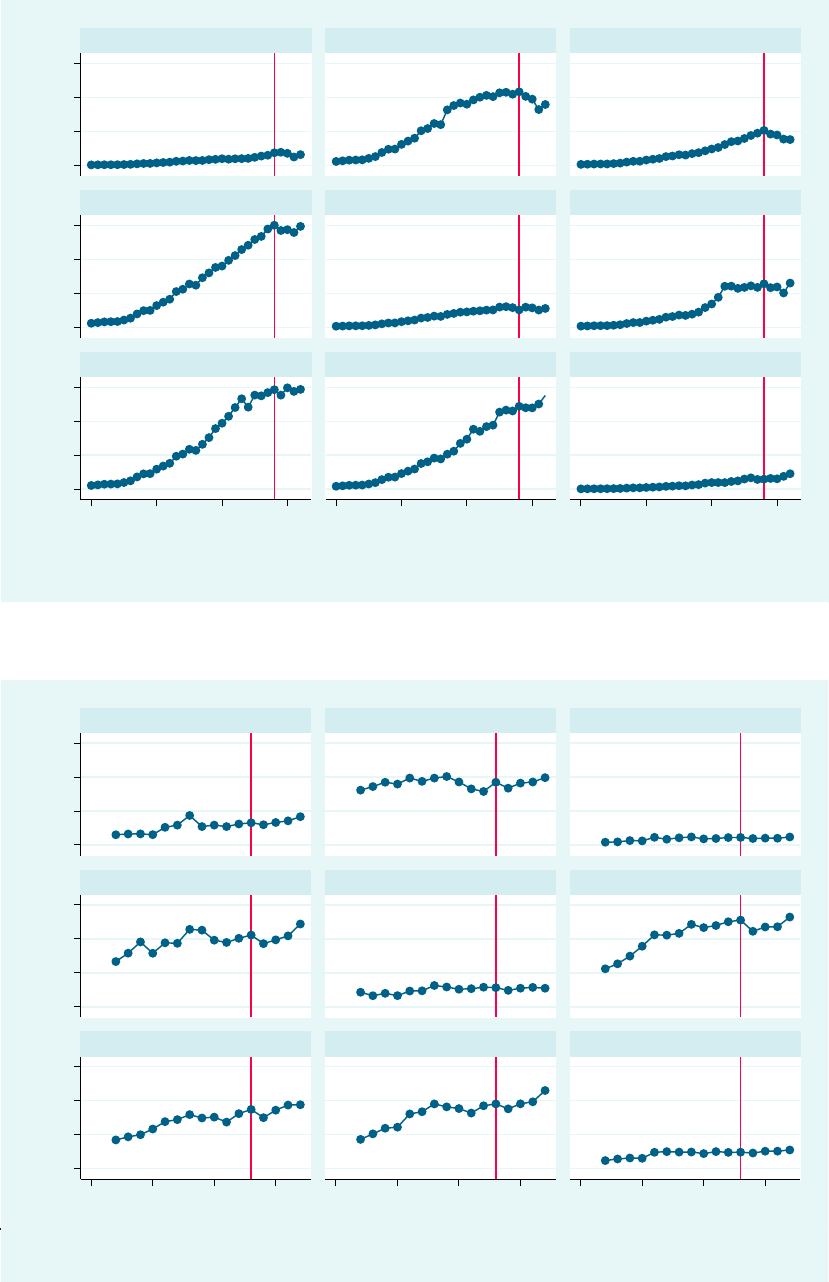

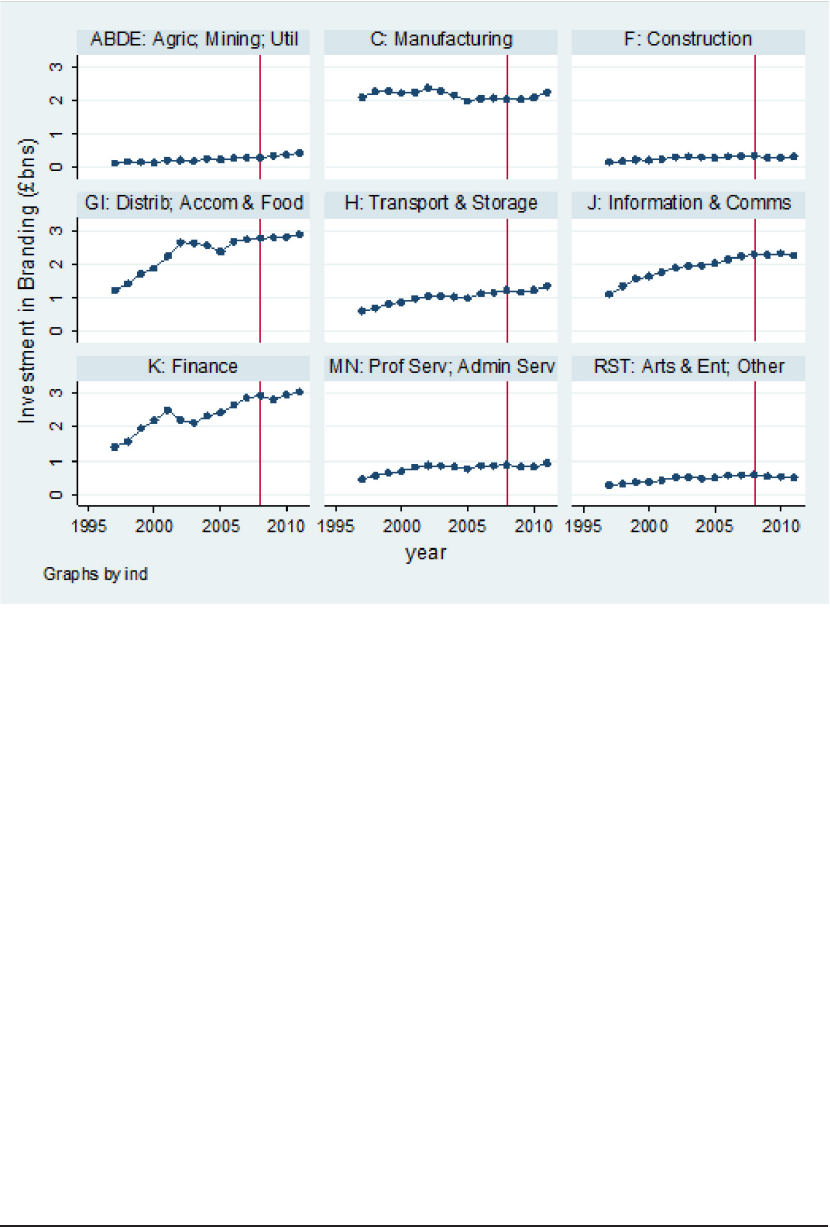

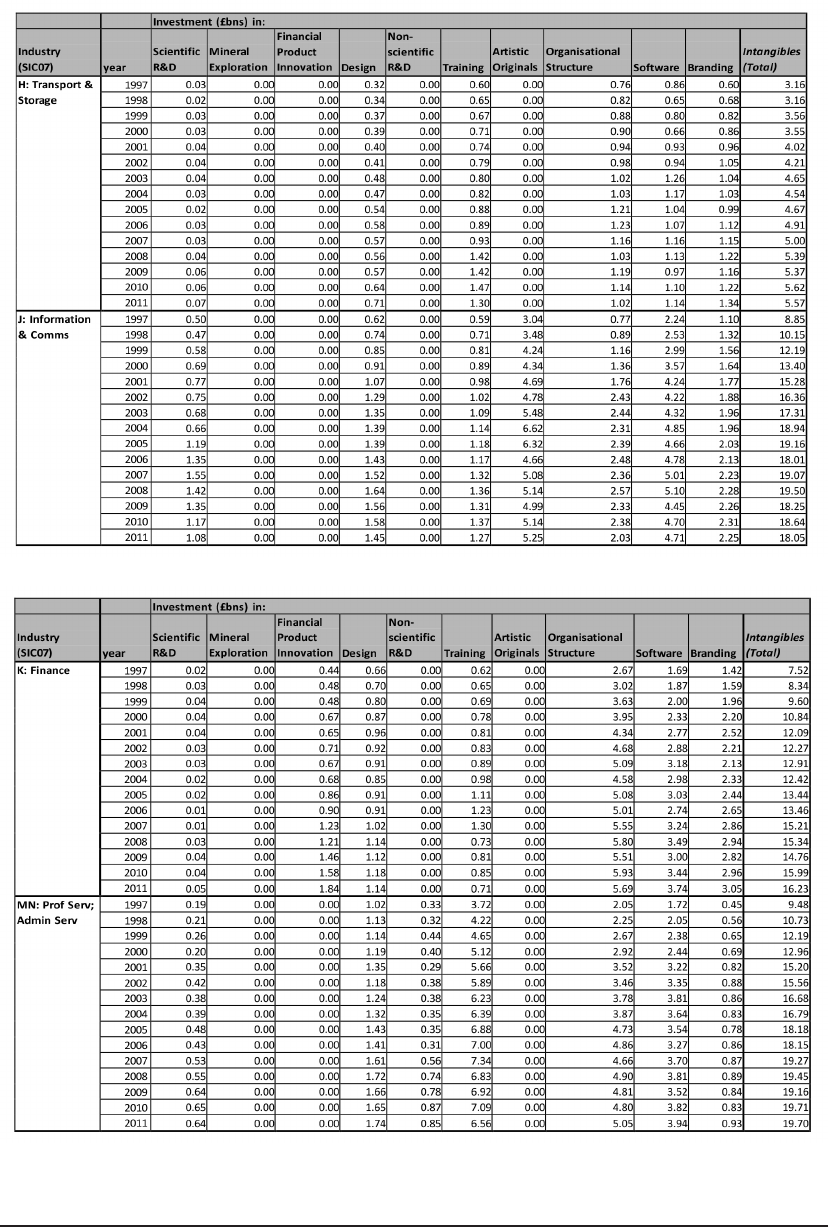

This appendix presents data for nominal intangible investment at the industry level, based on a

nine industry breakdown. The following charts present industry data for each intangible asset.

Where relevant, estimates of own-account and purchased estimates have been summed for

that category. Estimates for advertising and market research have also been summed to form

the asset category ‘Branding’. In each chart the line at 2008 marks the start of the recent

recession.

Figure A1.1: Industry-level investment in R&D

Note to figure: Y-axes for each chart have different scales

Estimating UK investment in intangible assets and Intellectual Property Rights

35

Figure A1.2: Industry-level investment in Mineral Exploration

.4 .6

.8

1 1.2

1995 2000 2005 2010

ABDE: Agric; Mining; Util

Investment in Mineral Exploration (£bns)

year

Graphs by indh1

Figure A1.3: Industry-level investment in Financial Product Innovation

0 .5 1 1.5 2

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

K: Finance

Investment in Financial Product Innovation (£bns)

year

Graphs by indh1

36