THE THEFT OF AMERICAN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY:

REASSESSMENTS OF THE CHALLENGE

AND UNITED STATES POLICY

update

to the

ip commission

report

2017

to the

ip commission

report

THE THEFT OF AMERICAN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY:

REASSESSMENTS OF THE CHALLENGE

AND UNITED STATES POLICY

update

This report was published on behalf of

The Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property

by The National Bureau of Asian Research.

The Report of the Commission on the e of American Intellectual Property (also known as the

IP Commission Report) was published in May 2013. This update was published in February 2017.

© 2017 by e National Bureau of Asian Research.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

v

Acknowledgments

Dennis C. Blair and Jon M. Huntsman, Jr.

1

Executive Summary

4

Introduction

4

New Developments to Counter IP e

7

State of the Problem: Damage Report

13

e Intellectual Property Rights Climate Abroad

16

Conclusion

17

Appendix: Examination of Recommendations

Adopted Recommendations

Recommendations Pending Action

20

About the Commissioners

24

List of Common Abbreviations

to the

ip commission

report

update

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Over three years ago we co-chaired a report by the Commission on the e of American

Intellectual Property. e report outlined the enormous magnitude of the problem and presented a

series of recommended actions to stem the loss of the lifeblood of American entrepreneurship. e

original report received, and continues to receive, widespread public attention. Congress adopted

several Commission recommendations to provide the executive branch and private industry with

unprecedented, powerful tools with which to ght intellectual property (IP) the. e executive

branch took a limited number of actions, while American businesses have continued to conne

their actions to defensive measures. e Commission still believes that IP the is one of the most

pressing issues of economic and national security facing our country. It is our unanimous opinion

that the issue has not received the sustained presidential focus and strong policy attention that

it requires.

is Commission remains composed of its original, extraordinary members. We are indebted

to our fellow Commissioners for their seless bipartisanship, insights, and help in explaining the

original report to the American people, policymakers, and members of the press for over three years.

e Commission’s sta has continued to be terrically eective. It includes several who have

remained in their positions, including Commission Director Richard Ellings and Deputy Director

Roy Kamphausen. Other stalwarts working on the Commission since the beginning are John

Graham, Amanda Keverkamp, and Joshua Ziemkowski. New commission sta who contributed

to the update to the original report include Dan Aum, Jessica Keough, Mariana Parks, Craig

Scanlan, and Sandra Ward. Special thanks are due to Mike Dyer, who shouldered more than his

fair share of this latest round of research, and to outside specialists for their guidance and reviews.

e Commission is grateful to e National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) and its Slade Gorton

International Policy Center, which have provided the unrestricted support that has underwritten

the Commission’s work and complete independence.

e importance of ensuring the viability and success of the U.S.-China relationship in part gave

rise to this Commission and our participation in it. We oer this update so that the United States

can better understand, prioritize, and solve a critical challenge.

Dennis C. Blair Jon M. Huntsman, Jr.

Co-chair Co-chair

1

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

e Commission on the e of American Intellectual Property is an independent and bipartisan

initiative of leading Americans from the private sector, public service in national security and foreign

aairs, academia, and politics. e members are listed in the section About the Commissioners.

e three purposes of the Commission are as follows:

1.

Document and assess the causes, scale, and other major dimensions of international intellectual

property (IP) the as they aect the United States.

2. Document and assess the role of China and other infringers in international IP the.

3. Propose appropriate U.S. policy responses that would mitigate ongoing and future damage and

obtain greater enforcement of IP rights (IPR) by China and other infringers.

IP the pervades international trade in goods and services due to lack of legal enforcement and

national industrial policies that encourage IP the by public, quasi-private, and private entities.

While some indicators show that the problem may have improved marginally, the the of IP remains

a grave threat to the United States. Since 2013, at the release of the IP Commission Report, U.S.

policy mechanisms have been markedly enhanced but gone largely unused. We estimate that the

annual cost to the U.S. economy continues to exceed $225 billion in counterfeit goods, pirated

soware, and the of trade secrets and could be as high as $600 billion.

1

It is important to note

that both the low- and high-end gures do not incorporate the full cost of patent infringement—an

area sorely in need of greater research. We have found no evidence that casts doubt on the estimate

provided by the Oce of the Director of National Intelligence in November 2015 that economic

espionage through hacking costs $400 billion per year.

2

At this rate, the United States has suered

over $1.2 trillion in economic damage since the publication of the original IP Commission Report

more than three years ago.

Scale and Cost of IP Theft

In three categories of IP the, new evidence and studies make it possible to provide more accurate

assessments of the damage done to the U.S. economy today than was the case in 2013.

3

ese

categories are counterfeit and pirated tangible goods, pirated soware, and trade secret the.

With regard to the rst category, the most reliable data available now suggests that in 2015 the

United States imported counterfeit and pirated tangible goods valued between $58 billion and

$118 billion, while counterfeit and pirated tangible U.S. goods worth approximately $85 billion

were sold that year worldwide.

4

e estimate by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

1

On November 18, 2015, William Evanina, national counterintelligence executive of the Oce of the Director of National Intelligence,

estimated that economic espionage through hacking costs the U.S. economy $400 billion a year, which falls within the range of the ndings

of the IP Commission. Evanina also stated, “We haven’t seen any indication in the private sector that anything has changed [in terms of

Chinese government involvement in hacking].” To date, the IP Commission has not found any evidence to the contrary. Chris Strohm,

“No Sign China Has Stopped Hacking U.S. Companies, Ocial Says,” Bloomberg, November 18, 2015, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/

articles/2015-11-18/no-sign-china-has-stopped-hacking-u-s-companies-ocial-says. e full report from the Oce of the Director of

National Intelligence is available from the IP Commission website at http://www.ipcommission.org/report/Evolving_Cyber_Tactics_in_

Stealing_US_Economic_Secrets_ODNI_Report.jpg.

2

Strohm, “No Sign China Has Stopped Hacking U.S. Companies, Ocial Says.”

3

e Report of the Commission on the e of American Intellectual Property (Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research on behalf of e

Commission on the e of American Intellectual Property, 2013), http://www.ipcommission.org/report/ip_commission_report_052213.pdf.

4

ese values were found using statistics from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and European Union

Intellectual Property Oce (EUIPO), Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact (Paris: OECD Publishing,

2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252653-en.

2

2017

Development (OECD) and the European Union Intellectual Property Oce (EUIPO) for the total value

of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported into the United States or counterfeit and pirated

tangible U.S. goods sold abroad on the conservative low end was $143 billion in 2015. e Commission

believes that these goods did not displace the sale of legitimate goods on a dollar-for-dollar basis and

estimates that at least 20% of the total amount of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods actually

displaced legitimate sales. us, the cost to the American economy, on the low end of the estimate,

is $29 billion.

5

e same OECD/EUIPO study found that while 95% of counterfeit goods seized by customs

ocials were protected by trademarks, only 2% were counterfeits of patent-protected goods.

6

is

means that although there is some overlap between our estimates of the value of counterfeit goods and

patent infringement, the vast majority of patent infringement is unaccounted for in this report. We

are disappointed that there is a paucity of reliable data on the economic costs of patent infringement,

but from anecdotal evidence we are led to believe the costs are substantial.

e proliferation of pirated soware is believed to be a much larger problem in scope than

statistics suggest because of the ease of downloading soware, ubiquitous use of soware across

industries and countries, and inadequate surveys. e value of soware pirated in 2015 alone

exceeded $52 billion worldwide. American companies were most likely the leading victims, with

estimated losses of at least 0.1% of the $18 trillion U.S. GDP, or approximately $18 billion.

7

e cost of trade secret the is still dicult to assess because companies may not even be aware

that their IP has been stolen, nor are rms incentivized to report their losses once discovered. As IP

the remains hard for rms to detect, much less obtain legal redress for, their incentives are to rely

more on their own eorts to conceal trade secrets and less on patents that entail public disclosure.

8

New estimates suggest that trade secret the is between 1% and 3% of GDP, meaning that the cost

to the $18 trillion U.S. economy is between $180 billion and $540 billion.

9

ese gures, while startling, do not take into account the second-order eects on the economy

from IP the. First, there is the practical matter of IP protection costs, which have skyrocketed,

especially in response to cyber-enabled IP the. More importantly, when trade secrets and other IP

are stolen by competitors, U.S. rms are discouraged from investing the substantial capital required

to innovate or eort required to work to be the rst movers to market. e immediate and long-term

loss of these advantages makes American rms less competitive globally.

China

China, whose industrial output now exceeds that of the United States, remains the world’s

principal IP infringer. China is deeply committed to industrial policies that include maximizing the

5

For purposes of aggregating the direct costs of IP the in the three listed categories—counterfeit and pirated tangible goods, soware

piracy, and trade secret the—the Commission estimates that no less than 20% of counterfeit sales would displace legitimate sales.

However, the precise amount is unknowable, because the purchase of counterfeit goods does not displace the sale of legitimate goods

on a dollar-for-dollar basis. For more discussion on the complex relationship between counterfeit and legitimate sales, see OECD, “e

Economic Impact of Counterfeiting,” 1998, 26–29, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/2090589.pdf.

6

OECD and EUIPO, Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods.

7

Business Soware Alliance (BSA), “Seizing Opportunity through License Compliance,” BSA Global Soware Survey, May 2016,

http://globalstudy.bsa.org/2016/downloads/studies/BSA_GSS_US.pdf.

8

R. Mark Halligan, “Trade Secrets v. Patents: e New Calculus,” Landslide, July/August 2010, http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/

migrated/intelprop/magazine/LandslideJuly2010_halligan.authcheckdam.pdf.

9

Center for Responsible Enterprise and Trade (CREATe.org) and PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Economic Impact of Trade Secret e: A

Framework for Companies to Safeguard Trade Secrets and Mitigate Potential reats,” 2014, https://create.org/resource/economic-impact-of-

trade-secret-the.

3

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

acquisition of foreign technology and information, policies that have contributed to greater IP the.

IP the by thousands of Chinese actors continues to be rampant, and the United States constantly

buys its own and other states’ inventions from Chinese infringers. China (including Hong Kong)

accounts for 87% of counterfeit goods seized coming into the United States.

10

China continues to obtain American IP from U.S. companies operating inside China, from

entities elsewhere in the world, and of course from the United States directly through conventional

as well as cyber means. ese include coercive activities by the state designed to force outright IP

transfer or give Chinese entities a better position from which to acquire or steal American IP.

U.S. Policy Response

Aer the release of the IP Commission Report in May 2013, the Obama administration and

Congress made important procedural changes to how the United States defends itself from IP the

and related cyberattacks, but they have been applied unevenly.

First, there are several positive developments. Chief among them is that cyberattacks may have

declined in volume since about 2014, although whether this is a result of a crackdown in China

on responsible units in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) or other factors is not entirely clear.

In any case, the cyber units of the PLA may have responded by shiing their tactics from blatant

mass hacking of U.S. entities to a more targeted and discreet approach.

11

Second, the gravity and complexity of IP the are better understood today than in 2013. Our

report and other studies raised public awareness through extensive media coverage and government

attention. e IP Commission Report continues to be cited by the world’s press and commentators.

e report was downloaded over 20,000 times in the rst week of its release and over 200,000 times

since then. It has come to be viewed as the foundational study in the eld.

Implementation is the major challenge today. e Obama administration and Congress adopted

some of the report’s key recommendations that set in place the legal basis for combatting IP the

successfully. e report’s major impact is Section 1637 of the 2015 National Defense Authorization

Act (NDAA). e law requires the president to issue a report on economic cyberespionage and on

actions taken by the executive branch against those who are stealing American IP through cyber

means. More importantly, the language gives the president the power to sanction foreign entities,

from persons to companies to countries. e deadline for issuance of the report was June 17, 2015.

Unfortunately, however, the report was not published until November 2016, and it gives no indication

that President Obama used Section 1637 to sanction foreign IP infringers.

In addition, last year Congress passed, and President Obama signed, the Defend Trade Secrets

Act of 2016, which, among other things, creates a private right of action for U.S. entities under the

Economic Espionage Act. is was another IP Commission recommendation. e president took into

account some of our recommendations for cybersecurity when he implemented the administration’s

Cybersecurity National Action Plan and signed Executive Order 13691 to mitigate vulnerabilities

in cyberspace and increase cooperation between the private and public sectors on this issue. e

National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center has proved eective, as far as we

can ascertain.

10

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, “Intellectual Property Rights Seizure Statistics Fiscal Year 2015,” 2016, https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/

les/assets/documents/2016-Apr/FY%202015%20IPR%20Stats%20Presentation.pdf.

11

FireEye iSight Intelligence, “Red Line Drawn: China Recalculates Its Use of Cyber Espionage,” Special Report, June 2016,

https://www.reeye.com/content/dam/reeye-www/current-threats/pdfs/rpt-china-espionage.pdf.

4

2017

Introduction

As the authors of the original Report of the Commission on the e of American Intellectual

Property (also known as the IP Commission Report), we were encouraged by the widespread interest

in the report and its impact on new legislation. In addition to the high volume of downloads, the

report was regularly cited, quoted, or referred to in the national and international media, including

the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and Economist.

We are pleased that Congress and the Obama administration took the lead from our report

and implemented several of our top recommendations. Congress gave the president the power to

sanction foreign entities that engage in cyberespionage of IP and gave U.S. entities private right of

action in federal courts against thieves of their trade secrets. For its part, the Obama administration

set up a mechanism to sanction foreign persons engaged in “signicant malicious activities.”

12

Despite the success of the report and resulting legislation, there is still much work that needs to be

done. We estimate that at the low end the annual cost to the U.S. economy of several categories of IP

the exceeds $225 billion, with the unknown cost of other types of IP the almost certainly exceeding

that amount and possibly being as high as $600 billion annually.

13

Further, while cyberespionage may

have decreased from some actors, several sources report that the worst and most capable actors still

persist in hacking for economic gain. IP thieves continue to use traditional means to attack targets.

What follows is an update to our original report. is update begins with an overview of the

legislative and executive actions that the U.S. government has taken since 2013. It moves on to assess

the economic cost of IP the and discuss the challenges to IP protections abroad that persist despite

attempts to deal with the problem. In the conclusion, we argue that Section 1637 of the 2015 NDAA

needs to be implemented and that many of our original recommendations remain relevant and ripe

for adoption. Our recommendations are outlined in detail in the appendix.

New Developments to Counter IP Theft

Aer the release of the IP Commission Report in May 2013, the Obama administration and

Congress took several actions to reduce the the of American IP. Some of the policies enacted have

borrowed from the recommendations that the Commission made in 2013, while others have fallen

short and le the Commission wanting more. Outlined below are the statutory and executive actions

that the U.S. government has implemented over the past three-plus years:

Indictment of ve PLA ocers. One year aer the release of the IP Commission Report, the

Department of Justice indicted ve members of PLA unit 61398 in Shanghai on economic espionage

charges. e indictment alleges the PLA ocers hacked into the networks of several U.S. companies

and maintained access over several years to steal trade secrets and other sensitive information.

e indictment of the ve ocers signied a break with the Obama administration’s strategy of

12

“Blocking the Property of Certain Persons Engaging in Signicant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities,” Executive Order 13694, April 1,

2015, Code of Federal Regulations, title 3 (2015), 297–99, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2016-title3-vol1/pdf/CFR-2016-title3-vol1-

eo13694.pdf.

13

As noted in the Executive Summary, in November 2015 William Evanina, national counterintelligence executive of the Oce of the Director

of National Intelligence, estimated that economic espionage through hacking costs the U.S. economy $400 billion a year, which is within the

range of the IP Commission’s ndings. See Strohm, “No Sign China Has Stopped Hacking U.S. Companies, Ocial Says.” e full report

from the Oce of the Director of National Intelligence is available from the IP Commission website at http://www.ipcommission.org/

report/Evolving_Cyber_Tactics_in_Stealing_US_Economic_Secrets_ODNI_Report.jpg.

5

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

quietly pressuring the Chinese government to establish mutually acceptable norms in cyberspace.

14

However, the indictment is largely symbolic; the PLA ocers will likely never be tried in a U.S.

court as they are unlikely to travel to the United States. e action seemed intended to shame the

People’s Republic of China (PRC) as publicly as possible, but in reality it probably served to disperse

the hackers away from the PLA unit and the associated unit headquarters, without achieving real

punishment for cyberattacks.

2015 National Defense Authorization Act, Section 1637, Actions to Address Economic or Industrial

Espionage in Cyberspace. e language of the section is remarkably similar to the Deter Cyber e

Act, which was introduced in its original sanction-less form in May 2013 by Senator Carl Levin,

then chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. (e bill cosponsors included Senator

John McCain, current chairman of the committee.) In May 2014 the Deter Cyber e Act was

reintroduced with the sanctions provision and was referred to the Senate Banking, Housing, and

Urban Aairs Committee, where no action was taken. In December 2014, Section 1637 was included

in the 2015 NDAA.

Section 1637 has two major components. First, it directs the president to submit a report to

Congress that contains a list of countries that engage in “economic and industrial espionage in

cyberspace” and a list of technologies or services that are being targeted by foreign actors. e

list of countries is similar to that of the Special 301 Report published by the United States Trade

Representative (USTR). Both require “priority” categories for the most egregious oending countries.

e report also must identify the actions taken by the president to “decrease the prevalence of

economic or industrial espionage in cyberspace.”

15

e National Counterintelligence and Security

Center released the report in November 2016—some seventeen months late. e report outlines

how state intelligence services have improved their cyberespionage techniques over the past several

years while U.S. companies have become more vulnerable targets due to increased use of the cloud

and other factors. e report concludes that the cost from cyber the to U.S. businesses appears

to be increasing.

16

Second, and more importantly, the bill authorizes the president “to prohibit all transactions in

property” of any person who the president determines “knowingly engages in economic or industrial

espionage in cyberspace.”

17

is authority is an expansion of the long-standing International

Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). ere are two points worth considering on what counts

as a “person.” First, the bill is limited to foreign persons. erefore, people within the United States

still must be prosecuted under the Economic Espionage Act. Second, IEEPA has been used for many

years, and it has targeted organizations as well as people.

14

Michael S. Schmidt and David E. Sanger, “5 in China Army Face U.S. Charges of Cyberattacks,” New York Times, May 19, 2014, http://www.

nytimes.com/2014/05/20/us/us-to-charge-chinese-workers-with-cyberspying.html.

15

U.S. Congress, Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, 113th Cong., Public Law

113-291 (Washington, D.C., December 19, 2014).

16

Oce of the Director of National Intelligence, National Counterintelligence and Security Center, “Evolving Cyber Tactics in Stealing U.S.

Economic Secrets: Report to Congress on Foreign Economic Collection and Industrial Espionage in Cyberspace 2015,” 2016, available

at http://www.ipcommission.org/report/Evolving_Cyber_Tactics_in_Stealing_US_Economic_Secrets_ODNI_Report.jpg. Much of the

data in the report only goes through 2015. For a report dated November 2016, we had hoped that more current data would be available.

e report also lacks the priority country list and the description of actions taken by the executive to decrease economic espionage in

cyberspace, as mandated by Section 1637. As noted above, the report concludes that the problem is growing worse due to several factors.

ese ndings would seem to contradict President Obama’s assertion that cyber the would get better in light of the agreement he struck

with President Xi Jinping.

17

For the purposes of Section 1637, cyberspace is dened as “the interdependent network of information technology infrastructures” and

includes “the internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers.” See U.S. Congress,

Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015.

6

2017

Five months aer this legislation was signed into law, President Obama signed Executive Order

13694 invoking the IEEPA emergency powers as urged by Congress, but unfortunately he apparently

never applied them to address the problem of IP the. See the section below on Executive Order

13694 for more information.

National Cybersecurity Protection Act of 2014. is law amends the Homeland Security Act of

2002 and codies the Department of Homeland Security’s cybersecurity operations center (the

National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center, or NCCIC). It grants authority

for the Department of Homeland Security to work with private and public entities to encourage

information sharing, including with international partners. It further instructs the NCCIC to report

to Congress on several issues, including the secretary’s recommendations for how to “expedite the

implementation of information-sharing agreements” between the public and private sectors and the

NCCIC’s progress in creating the center and implementing the law. e act also introduces a federal

agency “data breach notication” law, requiring federal agencies to notify Congress and individuals

aected by a data breach as quickly as possible. (ere are already 47 states with similar data statutes

requiring agencies to alert applicable persons.)

Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) of 2014. is law amends the Federal

Information Security Management Act of 2002 and instructs agencies to update their monitoring

systems for identifying data security compliance. Currently these processes require a lot of

redundant paperwork. FISMA outlines responsibilities for agencies and forces them to develop

better information security practices.

Cybersecurity Workforce Assessment Act of 2014. is act mandates that the Department of

Homeland Security review, update, and bolster its cybersecurity workforce. It also requires the

secretary of homeland security to develop a strategy to enhance “the readiness, capacity, training,

recruitment, and retention of the cybersecurity workforce of the Department.”

Cybersecurity Enhancement Act of 2014. With the aim to enhance the security of federal networks

and to “support the development of a voluntary, consensus-based, industry-led set of standards,”

the Cybersecurity Enhancement Act of 2014 authorizes the National Institute of Standards

and Technology to coordinate and consult with government agencies and the private sector to

develop best practices, including establishing research centers and scholarships for cultivating

cybersecurity professionals.

Executive Order 13691 of February 13, 2015, promoting private-sector cybersecurity information

sharing. Executive Order 13691 establishes “information-sharing and analysis organizations” to

strengthen the security cooperation among private industries, nongovernmental organizations, and

the federal government. e administration hopes these organizations will help U.S. rms in the

asymmetrical ght against state-sponsored cyberespionage.

Executive Order 13694 of April 1, 2015, blocking the property of certain persons engaging in

signicant malicious cyber-enabled activities. As urged by Congress in Section 1637 of the 2015

NDAA, President Obama signed Executive Order 13694 blocking the transfer, payment, or export

of property of individuals who have engaged in cyberespionage directed against the “national

security, foreign policy, economic health, or nancial stability of the United States.” e executive

order specically states that it will apply to individuals engaged in misappropriating trade secrets

for commercial or competitive advantage as well as to the commercial entities in receipt of such

information. President Obama declared that the national emergency would continue for another

7

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

year on March 29, 2016, as required by law. As of December 2016, Executive Order 13694 had yet to

be used against any individual in response to IP the.

18

Executive Order 13718 of February 9, 2016, establishing the Commission on Enhancing National

Cybersecurity. President Obama established the bipartisan Commission on Enhancing National

Cybersecurity to make “detailed recommendations to strengthen cybersecurity in both the public

and private sectors” through raising awareness, studying risk management strategies, and developing

methods to improve the adoption of best practices throughout the government. e commission’s

goal was to seek input from both cybersecurity experts and the victims of signicant cybersecurity

incidents to identify barriers to improved cybersecurity. e commission submitted its nal report

in early December 2016.

Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016. Signed into law on May 11, 2016, the bipartisan Defend Trade

Secrets Act establishes private right of action in federal court for U.S. entities that have had their

trade secrets stolen and oers them protections in the course of a trial to prevent their trade secrets

from becoming public. is was a key recommendation of the IP Commission in 2013. Prior to the

passage of the act, a victim of trade secret the could only seek a remedy with a civil suit in a state

court unless the Department of Justice led a criminal suit, which was rare.

19

e act also requires

the Department of Justice to submit a report to Congress on the size and scope of trade secret the

outside the United States no later than one year aer the date of enactment of the law and to oer

recommendations for combating such the. At the time of writing, the report, if submitted, is not

publicly available

IPEC Joint Strategic Plan on Intellectual Property Enforcement FY2017–2019. Published by the Oce

of the Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator (IPEC), this report was mandated by the

Prioritizing Resources and Organization for Intellectual Property Act and presents an account of

the economic cost of IP the and the various methods employed to commit IP-related crime. It

then oers several recommendations for securing cross-border trade and promoting frameworks to

enhance IPR enforcement.

20

e report was released in the nal month of the Obama administration,

and the eect on the Trump administration is yet to be determined.

State of the Problem: Damage Report

Despite executive and legislative action to stem the damage from IP infringement, the incentives

to steal IP persist, due in part to weak enforcement and penalties and in part to foreign industrial

policies and practices. e annual cost to the U.S. economy from IP the remains in the hundreds of

billions of dollars. is update to the IP Commission Report provides a conservative, low-end estimate

of the cost of IP the in three categories—counterfeit and pirated tangible goods, soware piracy,

and trade secret the—to be in excess of $225 billion, and the cost is possibly as high as $600 billion.

18

Executive Order 13694 was amended on December 29, 2016, and applied to sanction nine individuals and entities “in response to the

Russian government’s aggressive harassment of U.S. ocials and cyber operations aimed at the U.S. election.” “Executive Order—Taking

Additional Steps to Address the National Emergency with Respect to Signicant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities,” White House, Press

Release, December 29, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-oce/2016/12/29/executive-order-taking-additional-steps-address-

national-emergency.

19

“Congress Authorizes Federal Cause of Action for Trade Secret Misappropriation,” Lexology, 2006, http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.

aspx?g=9c07d09d-67b7-4937-af54-c7a313bcb85e.

20

Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator, U.S. Joint Strategic Plan on Intellectual Property Enforcement FY2017–2019: Supporting

Innovation, Creativity & Enterprise (Washington, D.C., December 2016), https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/les/omb/IPEC/

2016jointstrategicplan.pdf.

8

2017

The Continuing Signicance of the Problem

e threat to American IP-intensive industries stems from the diculty of enforcing protections

against advanced and persistent foreign threats. Law enforcement lacks the capacity to patrol and

protect the vast U.S. business community. When foreign actors are implicated in stealing American

IP, it is highly unlikely that they will ever be brought to justice in a U.S. court, as evidenced by

the indictment of the ve PLA ocers implicated in the the of IP from six U.S. companies.

21

e problem is made worse by foreign industrial policies and practices that rely on securing new

technologies cheaply to catch up with developed economies.

e threat of IP the is in turn signicant because of IP’s contribution to the U.S. economy.

IP protection is important to every business, as trade secrets and trademarks pervade the private

sector. According to the Global Intellectual Property Center of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce,

sales from IP-intensive rms totaled $6.9 trillion in 2013. IP-intensive industries are also responsible

for 56 million jobs in the United States—roughly 35% of the U.S. labor force. Moreover, a job with

an IP-intensive company pays on average 26% more than a job with a non-IP-intensive company.

22

The Diculty in Measuring the Damage

Measuring the economic impact of IP infringement and counterfeit goods is extraordinarily

dicult because of the illicit nature of piracy and trading in counterfeit goods, the ease of using

pirated soware, and the disincentives associated with reporting trade secret the. Victims of trade

secret the—to the extent that they are aware of the crime—are oen reluctant to share information

on the resulting nancial loss (when such the necessitates disclosure) out of fear of declining

investment opportunities or diminished market valuation.

Most statistics of trade in counterfeit tangible goods are based on seizure data reports from the

Customs and Border Patrol (CBP), with the understanding that customs ocials only capture a small

portion of counterfeit goods entering U.S. territory at the border and the statistics do not account for

counterfeit goods exchanged within the United States. ey also do not capture data for counterfeit

U.S. goods sold in foreign markets, nor do they take into account the vast amount of pirated goods,

which is even more dicult to measure. Moreover, even if the total amount of pirated and counterfeit

goods entering the United States could be quantied, this gure would only represent the value of

these goods and not necessarily the value of lost revenues. Finally, it is dicult to measure how

many buyers know that what they are purchasing is counterfeit and would not otherwise be in the

market for legitimate goods at an authorized price.

Despite these diculties, the damage to the U.S. economy can still be estimated by using existing

data and proxies. e following discussion provides a range for the cost to the U.S. economy of

counterfeit and pirated tangible goods, soware piracy, and trade secret the.

Estimate of the Cost of IP Theft

Counterfeit and pirated tangible goods. In 2016, the OECD and EUIPO used worldwide seizure

statistics from 2013 to calculate that up to 2.5%, or $461 billion, of world trade was in counterfeit

21

“U.S. Charges Five Chinese Military Hackers for Cyber Espionage against U.S. Corporations and a Labor Organization for Commercial

Advantage,” U.S. Department of Justice, May 19, 2014, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-ve-chinese-military-hackers-cyber-

espionage-against-us-corporations-and-labor.

22

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Global Intellectual Property Center, “Employing Innovation across America,” 2016, http://image.uschamber.

com/lib/fee913797d6303/m/1/GIPC_Employing_Innovation_Report_2016.pdf.

9

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

or pirated products.

23

By applying this percentage to U.S. trade, we estimate that in 2015 the value

of these goods entering the U.S. market was at least $58 billion.

e United States, however, is a much larger market for imports than the average market. It is

nearly equivalent in size to the European Union, where the OECD/EUIPO study determined that

approximately 5% of imports are counterfeit or pirated tangible goods.

24

By using 5% as a proxy

for the proportion of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods in U.S. imports ($2.273 trillion),

25

we

estimate that the United States may have imported up to $118 billion of these goods in 2015. us,

anywhere from $58 billion to $118 billion of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods may have entered

the United States in 2015. is represents the approximate value of counterfeit and pirated tangible

goods (not services) entering the country.

With respect to counterfeit and pirated tangible U.S. goods sold in foreign markets, the

OECD/EUIPO study found that they accounted for nearly 20% of the value of reported worldwide

seizures.

26

In 2015, estimated worldwide seizures of counterfeit goods totaled $425 billion, meaning

that as much as $85 billion of counterfeit U.S. goods (20% of worldwide seizures) entered the world

market (including the U.S. market).

27

Certainly, in the absence of counterfeit goods some sales would never take place, and thus the

value of illegal sales is not the same as the sales lost to U.S. rms. e true cost to law-abiding U.S.

rms in sales displaced due to counterfeiting and pirating of tangible goods is unknowable, but it is

almost certain to be a signicant proportion of total counterfeit sales. For purposes of aggregating

the total cost to the U.S. economy of IP the, we have estimated that 20% of counterfeits might

have displaced actual sales of goods. When applied to the low-end estimate ($143 billion) of the total

value of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported into the United States and counterfeit and

pirated tangible U.S. goods sold abroad, the conservative estimate of the cost to the U.S. economy

is $29 billion. When applied to the high-end estimate ($203 billion), the cost to the U.S. economy is

estimated at $41 billion.

How much of that total is intercepted by customs ocials, where does it come from, and how does

it get to the United States? CBP releases the Intellectual Property Rights Seizure Statistics each year.

From the nearly 29,000 seizures in 2015, CBP seized $1.35 billion in counterfeit goods at the U.S.

border, or 1.2%–2.3% of the estimated total value of counterfeit goods entering the United States,

according to the approximation from the OECD/EUIPO model.

28

Worldwide, counterfeit goods

travel mostly by postal service (62%) and quite oen in small shipments of ten items or fewer (43%).

29

is makes seizing them extraordinarily dicult.

CBP also tracks from where the counterfeit goods are imported. Slightly more than half (52%) of

all counterfeit goods entering the United States come from mainland China.

30

is is signicantly

23

OECD and EUIPO, Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods. Because the dynamics of trade have changed since 2013, and because the

United States is a larger market for imports than the average country, the 2.5% gure is not directly applicable to the United States, but it can

provide a rough approximation in the absence of updated data.

24

Ibid.

25

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “U.S. International Transaction Tables,” December 2016, https://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2017/01%20

January/0117_international_transactions_tables.pdf. It should be noted that there are signicant dierences between the two economies,

including apparently more porous borders in the European Union. As a result, the EU economy is not a perfect proxy for the U.S. economy.

26

OECD and EUIPO, Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods.

27

Ibid.

28

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, “Intellectual Property Rights Seizure Statistics Fiscal Year 2015.”

29

OECD and EUIPO, Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods.

30

Ibid.

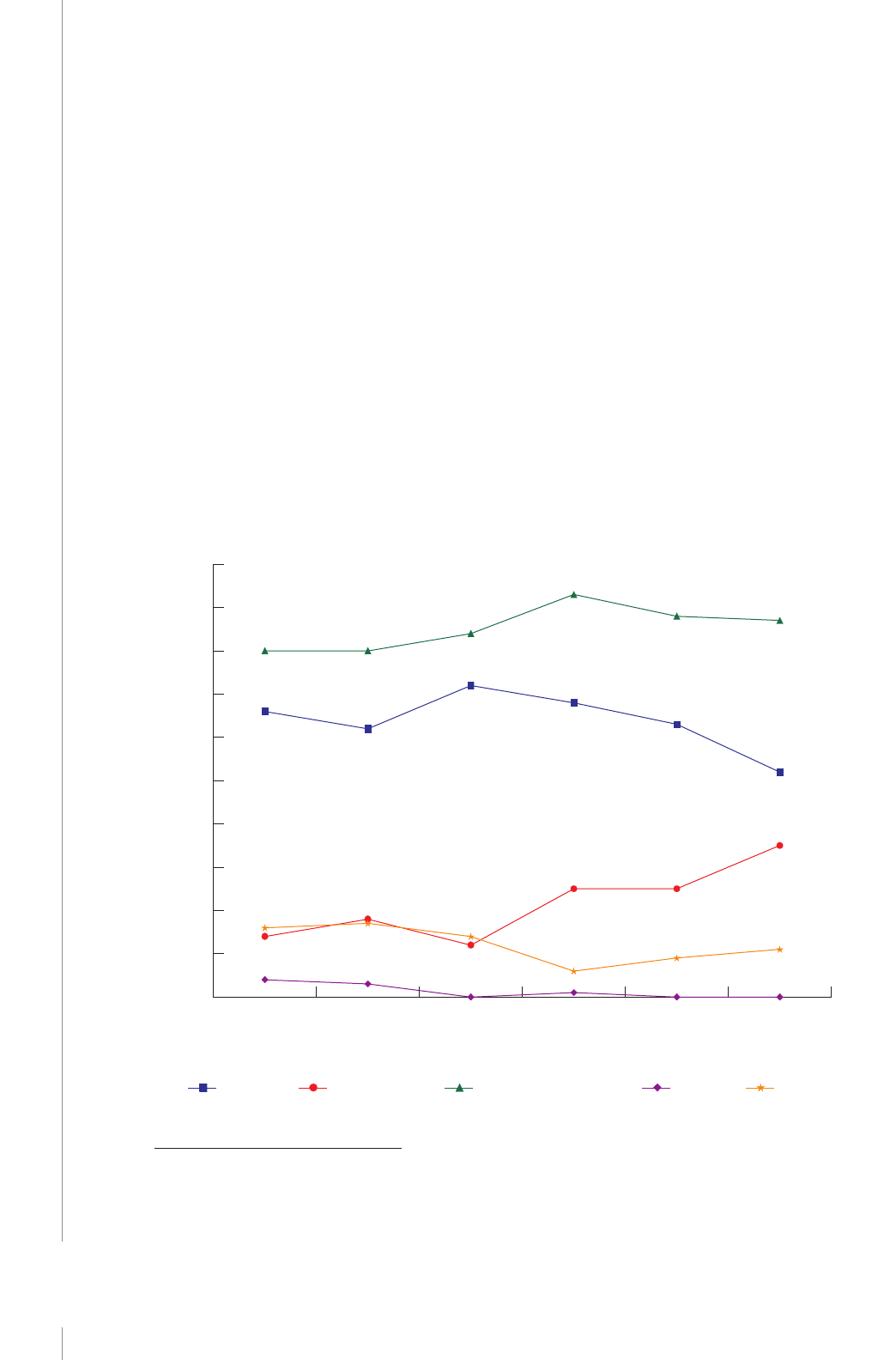

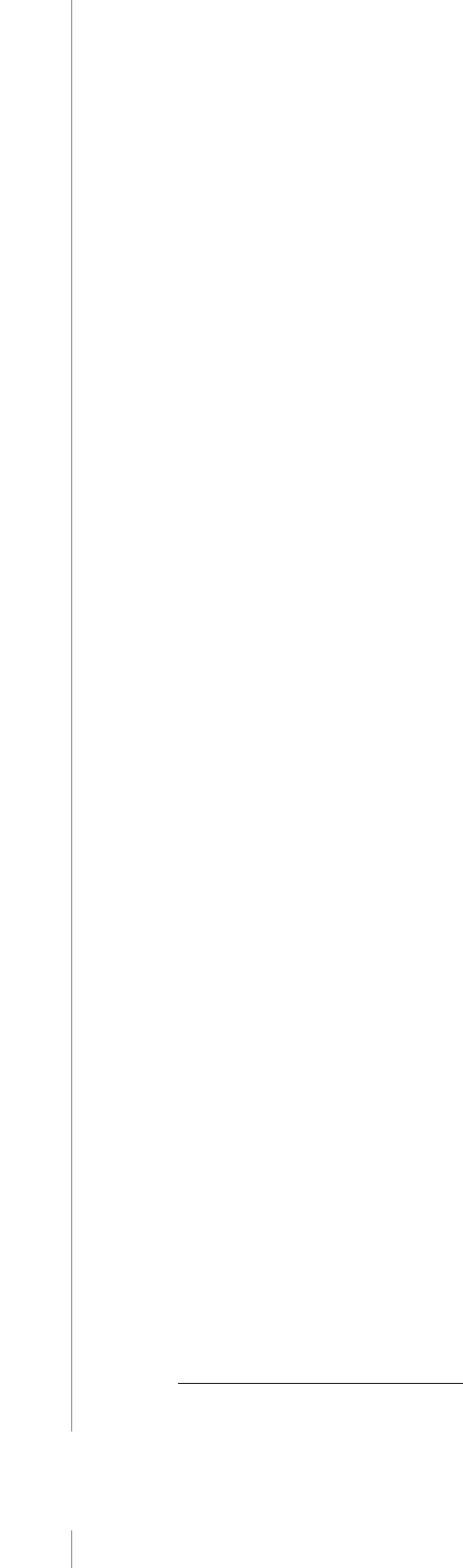

f i g u r e 1 Source economies of counterfeit goods

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Source of counterfeit goods (% share)

Year

China Hong Kong

China + Hong Kong

India Other economies

10

2017

lower than in 2013, which saw 68% of counterfeit goods coming from mainland China. However,

these improvements are oset by the increase in counterfeit goods imported from Hong Kong, which,

although a separate customs territory and economic entity, is under PRC sovereignty, allowing for a

more uid border with regard to the transport of goods in some cases. e PRC as a whole (including

Hong Kong) accounts for 87% of all counterfeit goods seized. is is only slightly lower than in 2013

and is slightly higher than the ve-year average. All other economies combined represent around

13% of imported counterfeit goods (see Figure 1). It is not just the United States that is receiving

counterfeits from China; 80% of the counterfeits seized in Canada are China-sourced as well.

31

Patent infringement. Unfortunately, our investigation has revealed no reliable quantitative data

on the economic cost of patent infringement to the U.S. economy, and therefore this is not included

in our total gures. However, through testimony to the Commission and anecdotal evidence in the

press, we can conclude that the cost to U.S. businesses from patent infringement abroad is at least in

the billions of dollars, although the full scale cannot be estimated.

32

China presents a mixed case. Of

particular note, China has become the top source of new patents, accounting for around one-third

31

“RFA: China Has Become the Largest Fake Product Source for Canada’s Online Market,” Chinascope, December 13, 2016, http://chinascope.

org/archives/10777.

32

As noted in our 2013 report, the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) estimated that U.S. companies suered $0.2 billion to $2.8

billion in losses from Chinese patent infringement in 2009 alone. USITC, China: Eects of Intellectual Property Infringement and Indigenous

Innovation Policies on the U.S. Economy (Washington, D.C., May 2011), 3–37, http://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4226.pdf.

11

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

of all new patents led in 2015.

33

However, many of these are “petty” or “utility” patents, which

grant protections to rights holders without questioning how innovative the subject matter might

be.

34

ese patent holders are then able to sue foreign companies bringing their IP into the Chinese

market. For more background on patent infringement, please see our original report.

Pirated software. e Business Soware Alliance (BSA) and International Data Corporation

track the rates and value of illicit soware in use throughout the world.

35

According to their

2015 data, the “shadow market” for globally pirated soware shrunk approximately 17% from

$62.7 billion in 2013 to $52.2 billion in 2015.

36

e low-end estimate for the cost to U.S. rms is

$18 billion, using 0.1% of U.S. GDP as a proxy—a percentage in line with BSA’s historical estimates

of global soware piracy.

37

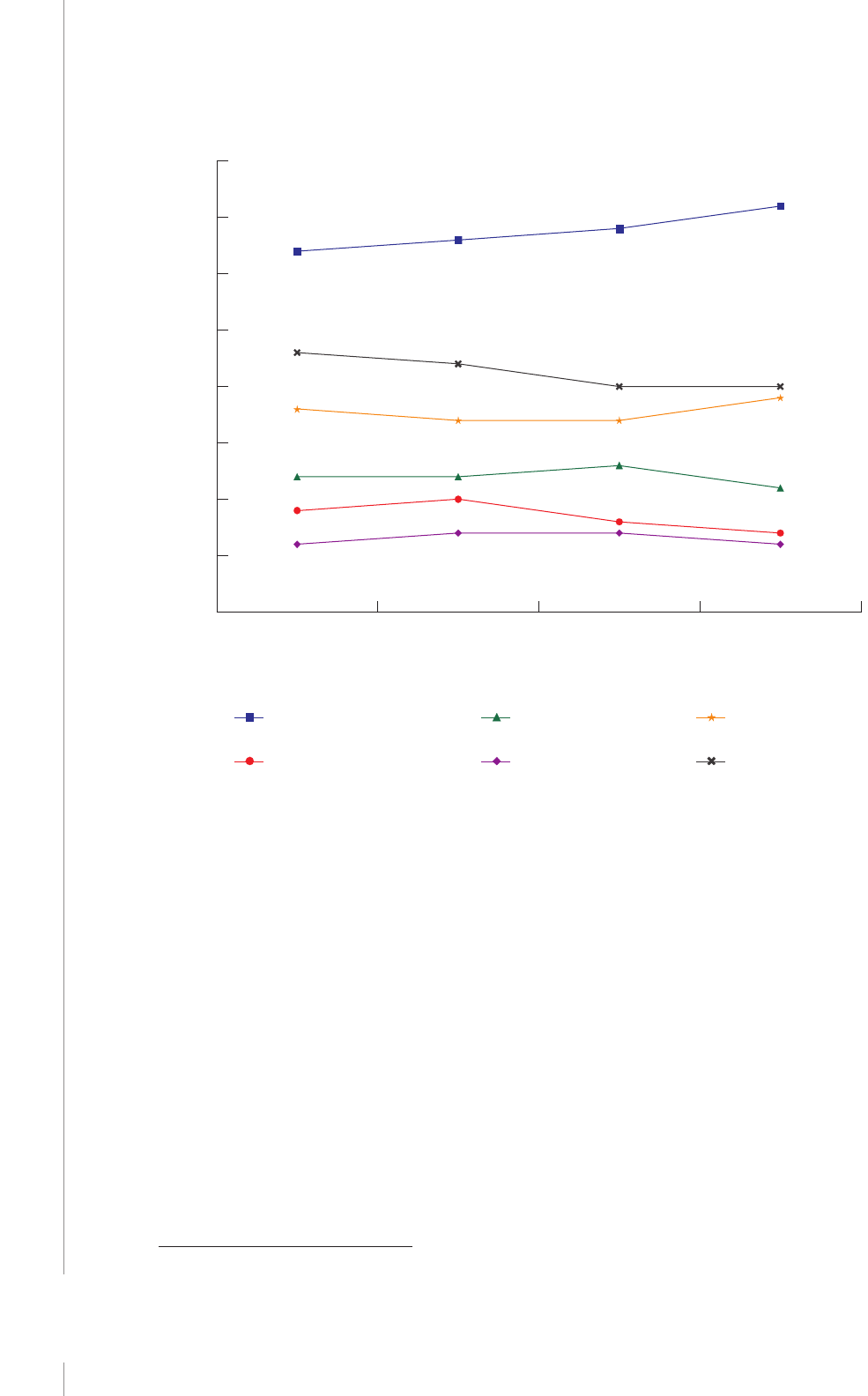

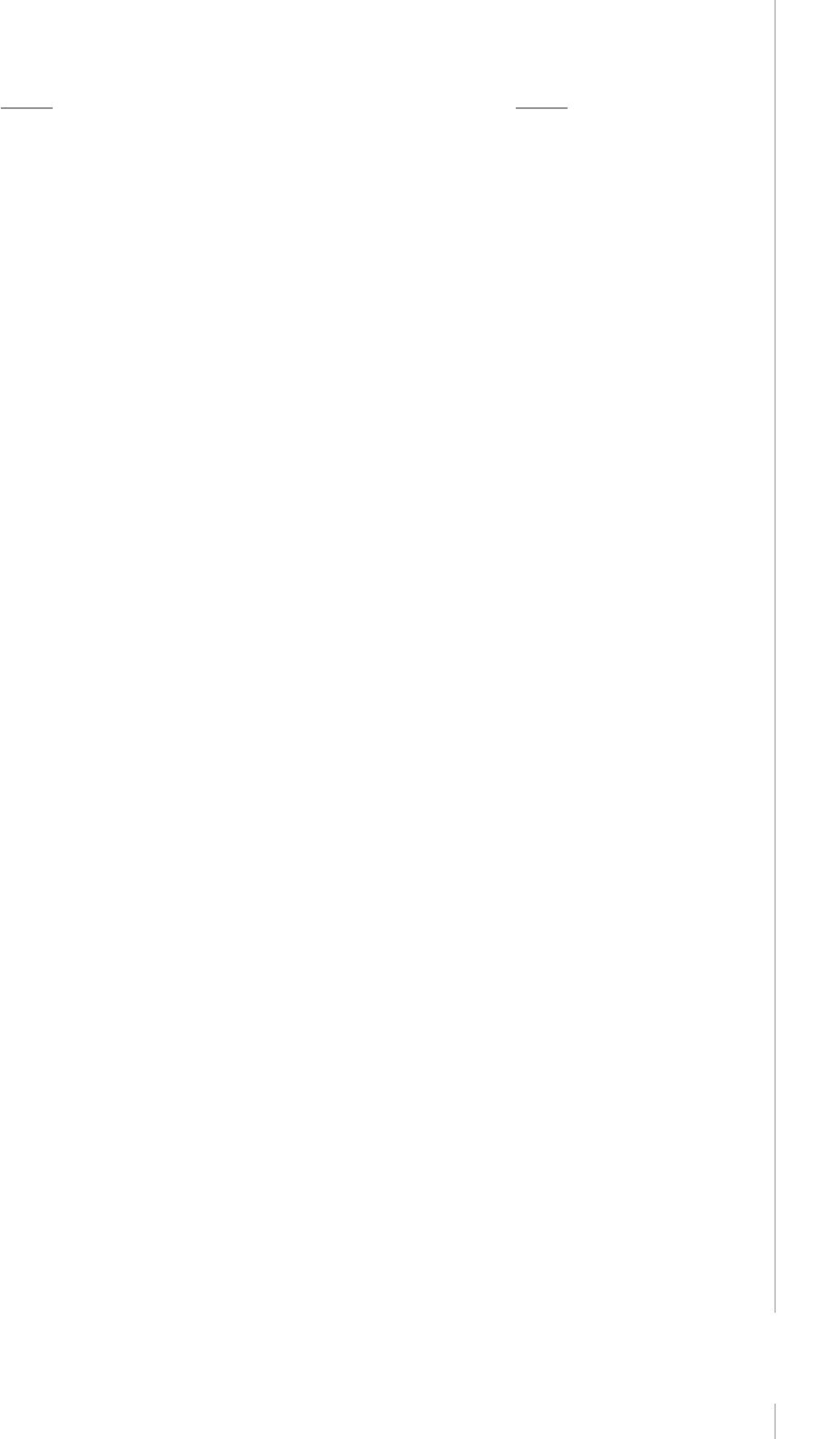

Globally the proportion of illicit soware was 39% in 2015, down from 43% in 2013. e

Asia-Pacic region remains the worst oender, with 61% of all soware in use being illicit—which

amounts to 36% of the world’s illicit soware value (see Figure 2).

38

Lost sales from pirated goods

are dicult to quantify.

e BSA study nds a strong correlation (0.78 coecient) between illicit soware and harmful

malware. In a separate study based on data from its wide network of users, Symantec discovered

“more than 430 million new unique pieces of malware, up 36 percent from the year before.”

39

Malware and ransomware are oen components of cyberattacks.

Theft of trade secrets. Of all the forms of IP the, trade secret the—in an increasing number

of cases enabled by cyberespionage—might do the greatest damage to the U.S. economy. In a

2014 study, “Economic Impact of Trade Secret e: A Framework for Companies to Safeguard

Trade Secrets and Mitigate Potential reats,” PricewaterhouseCoopers and the Center for

Responsible Enterprise and Trade, using several proxy measures, found that trade secret the

could be estimated to be between 1% and 3% of GDP.

40

Given this calculation, the economic

impact of trade secret the on the U.S. economy in 2015 is estimated to be between $180 billion

and $540 billion. Using the lower end of the range, we estimate that trade secret the costs the U.S.

economy at least $180 billion per year.

Cyber theft is a cheap way to avoid costly and time-intensive R&D that may simply be beyond

the thieves’ capacity. Foreign firms benefiting from the cyber theft of American IP are thus

able to sell goods and services developed using stolen IP at a much cheaper price than firms

investing in R&D organically.

33

“Global Patent Applications Rose to 2.9 Million in 2015 on Strong Growth from China; Demand Also Increased for Other Intellectual

Property Rights,” World Intellectual Property Organization, Press Release, November 23, 2016, http://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/

articles/2016/article_0017.html.

34

USITC, China: Eects of Intellectual Property Infringement and Indigenous Innovation Policies on the U.S. Economy.

35

We consider pirated soware as one category of pirated digital goods (other categories include all forms of digital media) that is separate

from pirated tangible goods. ere is much reliable data on counterfeit and pirated tangible goods based on seizure statistics from

customs and border patrol agencies, but much less data is available on pirated digital goods as a result of the ease of downloading and

sharing pirated digital content.

36

BSA, “Seizing Opportunity through License Compliance.”

37

CREATe.org and PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Economic Impact of Trade Secret e.”

38

BSA, “Seizing Opportunity through License Compliance.”

39

Symantec, “Internet Security reat Report,” vol. 21, April 2016, https://www.symantec.com/content/dam/symantec/docs/reports/istr-

21-2016-en.pdf.

40

CREATe.org and PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Economic Impact of Trade Secret e.”

f i g u r e 2 Global proportion of illicit software use by region

2009 2011 2013 2015

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Illicit software use by region (% share)

Year

Asia-Pacic

Central and Eastern Europe

Latin America

Middle East and Africa

North America

Western Europe

12

2017

Totaling It All Up

In summary, we estimate that the total low-end value of the annual cost of IP the in three major

categories exceeds $225 billion, or 1.25% of the U.S. economy, and may be as high as $600 billion,

based on the following components:

• e estimated low-end value of counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported and exported,

based on a conservative estimate that 20% of the cost of these goods detracts from legitimate

sales, is $29 billion. e high-end estimate for counterfeit and pirated tangible goods imported

and exported is $41 billion.

• e estimated value of pirated U.S. soware is $18 billion.

•

e estimated low-end cost of trade secret the to U.S. rms is $180 billion, or 1% of U.S. GDP.

e high-end estimate is $540 billion, amounting to 3% of GDP.

We have thus found no evidence that the Oce of the Director of National Intelligence’s

estimate of $400 billion is incorrect.

41

Again, these are only the direct costs of IP the that can

41

Strohm, “No Sign China Has Stopped Hacking U.S. Companies, Ocial Says.”

13

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

be roughly estimated. e indirect costs to the U.S. economy, such as the loss of competitiveness

and devaluation of trademarks, are more dicult to measure, but we conclude that they are no

less substantial. It is also important to note that these gures do not account for the economic

cost of patent infringement.

Innovation is the United States’ greatest competitive advantage.

42

e massive the of American

IP undermines that advantage, making the United States less competitive over the long term. Further,

IP-intensive jobs have a greater multiplier eect on employment than do other types of jobs. For every

high-tech job created in the United States, ve jobs are also created indirectly in a local economy.

43

China does not just steal the most American IP of any country; it targets the sectors at the forefront

of innovation that could create the best jobs for Americans in the 21st century. Firms in nascent

industries such as biotechnology and next-generation IT that have the greatest potential to drive

future growth in the U.S. economy are unfortunately under the greatest threat.

The Intellectual Property Rights Climate Abroad

Every year, the USTR reviews the development in IPR protection abroad and establishes watch

lists. In 2016 the USTR reviewed 73 trading partners for its Special 301 Report and listed 34 countries

on its Priority Watch List or Watch List. Only Ecuador and Pakistan moved o the Priority Watch

List.

44

ese watch lists are important for the U.S. government to identify the most salient issues

of IPR protection among U.S. trade partners. e Special 301 Report is not all negative; it also

identies best IPR practices by trading partners and other positive developments abroad. e 2016

report recognized China specically for overhauling its IPR laws and regulations and for signing

an expanded memorandum of understanding with the National Intellectual Property Rights

Coordination Center of the Department of Homeland Security.

45

In addition to the watch lists, the USTR announced that it would conduct four out-of-cycle reviews

in 2016 to encourage foreign nations to make continued progress on IPR issues. Specically, the

reviews would examine and make recommendations for Colombia, Pakistan, Spain, and Tajikistan.

e out-of-cycle reviews were not available from the USTR website at the time of writing.

The Special Case of China

As previously mentioned, China (including Hong Kong) is the source of 87% of counterfeit

physical goods entering the United States. It is not surprising, then, that in the “2016 China Business

Climate Survey Report” the American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China lists

IP infringement as a concern regarding doing business in China, with 23% of respondents listing

it as a top challenge.

46

is evidence is corroborated by the U.S.-China Business Council, which

found that IPR enforcement was the eighth-highest concern of U.S. companies it surveyed—an

improvement over the previous year. Of note, the top concerns for U.S. companies in the Business

42

Derek Scissors, “Fixing U.S.-China Trade and Investment,” American Enterprise Institute, April 13, 2016, https://www.aei.org/publication/

xing-us-china-trade-and-investment.

43

Enrico Moretti, e New Geography of Jobs (Boston: First Mariner Books, 2013).

44

USTR, “2016 Special 301 Report,” April 2016, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/les/USTR-2016-Special-301-Report.pdf.

45

Ibid.

46

American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China, “2016 China Business Climate Survey Report,” 2016, http://www.

amchamchina.org/policy-advocacy/business-climate-survey.

14

2017

Climate Survey are issues relevant to this report—inconsistent interpretation of regulations and

unclear laws—which is a sign that China’s regulatory regime is developing in uneven ways.

47

e Chinese government recognizes that it must reform its regulatory environment to support the

development of an IP-intensive economy that produces its own high-value products and to become

not just a “large IP country” but also a “strong IP country.”

48

e Chinese government has made

strengthening its IPR regime a goal since it enacted a series of laws in the 1970s. It signed on to the

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights in the 1990s and ultimately

joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

49

Yet China has only had IP courts since 2014

and is still reforming its laws and regulations.

To realize those reforms, China’s State Council issued a new action plan in 2016. Building on

a 2015 policy document outlining goals to develop a stricter IPR regime, the action plan, titled

“Opinion of the State Council on Accelerating the Construction of Intellectual Property Powers for

China as an Intellectual Property Strong Country under the New Situation—Division of Tasks,”

duplicates standing policy but also lists several priorities for reform of the IPR regime.

50

According to

analysis by Mark Cohen, a long-standing expert on China’s IP environment, the document suggests

that China is making a greater eort to raise the damages a victim can sue for in Chinese courts.

51

e action plan also stresses international cooperation and the placement of more IP ocials overseas

to protect Chinese companies. It goes on to encourage the study of China’s IP-intensive industries and

the use of scal policy to promote their development.

52

Taken as a whole, the plan appears to be more

geared toward fostering stronger IP-intensive industries at home than developing the rule of law.

In both its Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance and the Special 301 Report, the

USTR identies problems with trade secret the, soware piracy, and counterfeit physical goods.

53

e “2016 Special 301 Report” outlines several deciencies in China’s IPR regime that go uncorrected

in the most recent action plan:

Progress toward eective protection and enforcement of IPR in China is

undermined by unchecked trade secret the, market access obstacles to ICT

[information and communications technology] products raised in the name of

security, measures favoring domestically owned intellectual property in the name

of promoting innovation in China, rampant piracy and counterfeiting in China’s

massive online and physical markets, extensive use of unlicensed soware, and

the supply of counterfeit goods to foreign markets. Additional challenges arise

in the form of obstacles that restrict foreign rms’ ability to fully participate

in standards setting, the unnecessary introduction of inapposite competition

concepts into intellectual property laws, and acute challenges in protecting and

incentivizing the creation of pharmaceutical inventions and test data. As a result,

surveys continue to show that the uncertain intellectual property environment

47

U.S.-China Business Council, “USCBC 2016 Membership Survey: e Business Environment in China—Key Findings,” 2016, https://www.

uschina.org/sites/default/les/USCBC%202016%20Annual%20Member%20Survey%20%28ENG%29_1.pdf.

48

“New State Council Decision on Intellectual Property Strategy for China as a Strong IP Country,” China IPR, July 24, 2016, https://chinaipr.

com/2016/07/24/new-state-council-decision-on-intellectual-property-strategy-for-china-as-a-strong-ip-country.

49

Mingde Li, “Current IP Issues in China and the Multilateral Trading System,” Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, February 26, 2015,

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/Li_Mengde.pdf.

50

“New State Council Decision on Intellectual Property Strategy for China as a Strong IP Country.”

51

Ibid.

52

Ibid.

53

USTR, “2015 Report to Congress on China WTO Compliance,” December 2015, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/les/2015-Report-to-

Congress-China-WTO-Compliance.pdf.

15

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

is a leading concern for businesses operating in China, as intellectual property

infringements are dicult to prevent and remediate.

54

China also singles out high-tech sectors for special support in its ve-year plans. In testimony

to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Commission, Jen Weedon, formerly of the cybersecurity

rm FireEye, asserted that while all sectors are potential targets of Chinese cyberespionage, rms

in strategic industries identied in the 12th Five-Year Plan are targeted by a greater number of

advanced hackers sponsored by the Chinese government.

55

One such targeted high-tech sector is the

semiconductor industry. e Chinese government hopes that China can attain “world-class status”

in semiconductor production by 2030.

56

It aims to do so through subsidizing domestic rms, and

by what the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology calls “zero-sum tactics”

that hurt the overall industry and global economy but help Chinese rms. ese tactics include

the overt and covert the of IP, among others.

57

Numerous examples help demonstrate the scope of the Chinese industrial policy of gaining access

to foreign expertise in key sectors. For example, in the United Kingdom, the sensitive nuclear project

at Hinkley Point proposed for co-development with China General Nuclear Power Company was

delayed. It came to light that the Chinese rm was indicted (along with one of its senior employees,

Allen Ho) for “conspiracy to unlawfully engage and participate in the production and development

of special nuclear material outside the United States, without the required authorization from the

U.S. Department of Energy.”

58

Perhaps the most recent case is China’s development of the Micius satellite, considered the world’s

rst quantum communications satellite, which China launched into orbit in 2016. Scientists at

national laboratories and academic institutions around the world have been working on developing

technology based on quantum mechanics to create a communications system that is considered to

be completely secure from penetration. China is eager to develop this technology to protect its own

communications from potential adversaries like the United States. However, perhaps ironically,

China was able to develop quantum communications technology ahead of its rivals by incorporating

their research ndings. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Pan Jianwei, the physicist leading

the project, was quoted saying, “We’ve taken all the good technology from labs around the world,

absorbed it and brought it back.”

59

is may be just an innocent quip about how scientists share

their basic research ndings with one another across borders. However, it has been demonstrated

54

USTR, “2016 Special 301 Report.”

55

Jen Weedon, testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on Commercial Cyber Espionage and

Barriers to Digital Trade in China, Washington, D.C., June 15, 2015, http://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/les/Weedon%20Testimony.pdf.

56

“China’s Global Semiconductor Raid,” Wall Street Journal, January 12, 2017, http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-global-semiconductor-

raid-1484266212.

57

President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Report to the President: Ensuring Long-Term U.S. Leadership in Semiconductors

(Washington, D.C., January 2017), https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/les/microsites/ostp/PCAST/pcast_ensuring_long-term_us_

leadership_in_semiconductors.pdf. e other zero-sum tactics include forcing customers to buy domestic and forcing foreign companies

to transfer technology for market access. A fourth zero-sum tactic, not mentioned in the report from the President’s Council of Advisors

on Science and Technology, is barring foreign rms from providing certain services in the Chinese market. For example, value-added

telecommunications services cannot be provided by a foreign-owned entity. e best a foreign company can do is own 49% of an entity

providing such services because the necessary license can only be granted to a majority-Chinese-owned entity. is means that online stores

and cloud storage, among other services, have to be provided by the latter, forcing the foreign company to share the technology and prots

with a Chinese partner.

58

“U.S. Nuclear Engineer, China General Nuclear Power Company and Energy Technology International Indicted in Nuclear Power

Conspiracy against the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 14, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-nuclear-engineer-

china-general-nuclear-power-company-and-energy-technology-international.

59

Josh Chin, “China’s Latest Leap Forward Isn’t Just Great—It’s Quantum,” Wall Street Journal, August 20, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/articles/

chinas-latest-leap-forward-isnt-just-greatits-quantum-1471269555.

16

2017

that the Chinese government systematically collects information and secrets from abroad to further

its technology development goals, as illustrated by the cases discussed above.

Beyond security issues is the concern that Chinese rms are able to underbid competitors

because of unfair business practices, such as a rm enjoying preferential funding arrangements as

a state-owned enterprise or engaging in the the of IP and resources, as the U.S. Department of

Justice nds.

60

Not only do these business practices allow Chinese rms to outbid potential rivals;

they help Chinese researchers in the state sector develop competitive technology faster than some

of their international rivals.

Conclusion

e scourge of IP the and cyberespionage likely continues to cost the U.S. economy hundreds of

billions of dollars a year despite improved laws and regulations. e the of American IP is not just the

“greatest transfer of wealth in human history,” as General Keith Alexander once put it; IP the undercuts

the primary competitive advantage of American business—the capacity for innovation. IP-intensive

companies generate more jobs both directly and indirectly than rms in other sectors. e growth

of the U.S. economy and the strength of the U.S. labor market depend on the ability of Americans to

innovate and increase productivity. e scale and persistence of IP the, oen committed by advanced

state-backed groups, erode the competitiveness of U.S. rms and threaten the U.S. economy.

Apart from the economic costs of IP the are the political costs. Allowing persistent state-backed

IP the to continue represents the erosion of the norms between countries that buttress the

international order. e United States has chosen to uphold these norms for generations and

continues to uphold them when they are threatened in other domains. It should not give up on

leading toward a code of conduct in the cyber domain or on addressing the issue of IP the. Such

leadership requires that the United States enforce its own laws.

e commissioners were discouraged by the Obama administration’s inaction on IP the and

cyberespionage. Congress has implemented several of the recommendations from our 2013 report,

namely Section 1637 of the 2015 NDAA and the Defense Trade Secrets Act of 2016. Although the

president took steps to bring his emergency economic powers to bear on cyber-enabled IP the, the

Obama administration failed to bring any cases against the perpetrators of cybercrime or IP the.

e U.S. government has the capability and resources to address this problem. President Donald

Trump should make IP the a core issue in the early months of his administration. It is perhaps the

single best way to correct the problems in the Sino-U.S. relationship that he highlighted during his

campaign. To that end, several of this Commission’s recommendations (outlined in the appendix)

remain ripe for implementation, and we hope that the new Congress and administration will

examine them early in 2017. If the makeup of this Commission is any suggestion, there exists

broad bipartisan support for addressing IP the and safeguarding the competitive advantages of

U.S. rms, entrepreneurs, and workers.

60

“U.S. Nuclear Engineer, China General Nuclear Power Company and Energy Technology International Indicted in Nuclear Power

Conspiracy against the United States.”

17

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

APPENDIX: EXAMINATION OF RECOMMENDATIONS

Adopted Recommendations

Short-term Solutions

• Enforce strict supply-chain accountability for the U.S. government.

o According to the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Defense has

made some improvements in its supply-chain management, although much work remains

to be done.

Medium-term Solutions

• Amend the Economic Espionage Act to provide a federal private right of action for trade

secret the.

o The Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 created private right of action for victims of trade

secret theft in U.S. courts. The act also created protections for plaintiffs to conceal the

nature of their trade secrets.

• Strengthen U.S. diplomatic priorities in the protection of American IP.

o Additional IP attachés are posted abroad, including a dedicated IP attaché in Beijing.

Long-term Solutions

• Build institutions in priority countries that contribute toward a rule-of-law environment in

ways that protect IP.

o This long-term solution is arguably in progress. A key component of the Obama

administration’s Joint Strategic Plan on Intellectual Property Enforcement was building

capacity internationally to contribute to a rule-of-law environment.

Recommendations for Cybersecurity

• Implement prudent vulnerability-mitigation measures.

o This recommendation is being implemented through the Cybersecurity National

Action Plan and through Executive Order 13691 establishing information-sharing

and analysis organizations.

Recommendations Pending Action

Short-term Solutions

• Designate the national security adviser as the principal policy coordinator on the protection

of American IP to reect the president’s priority and to ensure interagency coordination on

this issue.

o Not implemented. The U.S. intellectual property enforcement coordinator, within the

Office of Management and Budget, is still the principal policy coordinator.

18

2017

• Provide statutory responsibility and authority to the secretary of commerce to serve as

the principal ocial responsible for eectively administering the president’s policies on

IP protection.

o Not implemented.

• Strengthen the International Trade Commission’s 337 process to sequester goods containing

stolen IP.

o Not implemented. However, Section 1637 of the 2015 NDAA allows the president to

sanction individuals and organizations found to be involved in economic espionage.

• Empower the secretary of the Treasury, on the recommendation of the secretary of commerce,

to deny the use of the U.S. banking system to foreign companies that repeatedly use or benet

from the the of American IP.

o Authority established but not exercised. The IEEPA allows the president to sanction

individuals and organizations and to “prohibit any transaction in foreign exchange.”

• Increase Department of Justice and FBI resources to investigate and prosecute cases of trade

secret the, especially those enabled by cyber means.

o

Partially implemented. Ad hoc evidence suggests that more resources have been dedicated,

but progress on this recommendation is difficult to quantify.

• Consider the degree of protection aorded to U.S. companies’ IP a criterion for approving

major foreign investments in the United States under the Committee on Foreign Investment

in the U.S. (CFIUS) process.

o Not Implemented. No relevant new legislation has passed and no new executive orders

have been implemented since 2008 that affect CFIUS.

• Require the Securities and Exchange Commission to judge whether companies’ use of stolen

IP is a material condition that ought to be publicly reported.

o Not implemented.

• Greatly expand the number of green cards available to foreign students who earn science,

technology, engineering, and mathematics degrees in American universities and who have a

job oer in their eld upon graduation.

o Not implemented.

Medium-term Solutions

• Make the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit the appellate court for all actions under

the Economic Espionage Act.

o Not implemented.

• Instruct the Federal Trade Commission to obtain meaningful sanctions against foreign

companies using stolen IP.

o Not implemented.

19

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

Long-term Solutions

• Develop a program that encourages technological innovation to improve the ability to detect

counterfeit goods.

o Not implemented.

• Ensure that top U.S. ocials from all agencies push to move China beyond a policy of

indigenous innovation toward becoming a self-innovating economy.

o Not implemented.

• Develop IP “centers of excellence” on a regional basis within China and other priority countries.

o Not implemented.

• Establish in the private nonprot sector an assessment or rating system of levels of legal

protection for IP, beginning in China but extending to other countries as well.

o Not implemented.

Recommendations for Cybersecurity

• Support U.S. companies and technology that can both identify and recover IP stolen through

cyber means.

o Not implemented.

• On an ongoing basis, reconcile necessary changes in the law with a changing technical

environment.

o Partially implemented on an ad hoc basis.

20

2017

ABOUT THE COMMISSIONERS

Dennis C. Blair is the Chairman of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA and the Co-Chair of

the Commission on the e of American Intellectual Property. He is the former commander

in chief of the U.S. Pacic Command and the former U.S. director of national intelligence.

Prior to rejoining the government in 2009, Admiral Blair held the John M. Shalikashvili Chair

in National Security Studies with the National Bureau of Asian Research and served as deputy

director of the Project for National Security Reform. From 2003 to 2006, Admiral Blair was

president and chief executive ocer of the Institute for Defense Analyses, a federally funded

research and development center based in Alexandria, Virginia, that supports the Department

of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, and the intelligence community. He also

has been a director of two public companies, EDO and Tyco International. During his 34-year

career with the U.S. Navy, he served on guided-missile destroyers in both the Atlantic and Pacic

eets and commanded the Kitty Hawk Battle Group. Ashore, Admiral Blair served as director

of the Joint Sta and held budget and policy positions on the National Security Council and

several major navy stas. A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Admiral Blair earned a master’s

degree in history and languages from Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar and was a White

House Fellow at the Department of Housing and Urban Development. He has been awarded four

Defense Distinguished Service medals and three National Intelligence Distinguished Service

medals and has received decorations from the governments of Japan, ailand, South Korea,

Australia, the Philippines, and Taiwan.

Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., is the former U.S. ambassador to China (2009–11), the former governor

of Utah (2005–9), and the Co-Chair of the Commission on the e of American Intellectual

Property. He is currently the Chairman of the Atlantic Council and Co-Chairman of No Labels.

Governor Huntsman was appointed U.S. ambassador to China by President Barack Obama and

conrmed by the Senate on August 7, 2009. As ambassador, he worked closely with U.S. business

owners to facilitate commerce in the growing Asian market and advocated for the release of U.S.

citizens wrongfully imprisoned. As governor of Utah, he cut waste and made government more

ecient. As a result, the state held its AAA bond rating and earned national accolades for debt

management. Utah also ranked number one in the United States in job creation and was named

the best-managed state by the Pew Research Center. Prior to serving as governor, he was named

U.S. ambassador to Singapore, becoming the youngest head of a U.S. diplomatic mission in a

century. Governor Huntsman also served as U.S. trade ambassador under President George W.

Bush, during which time he helped negotiate dozens of free trade agreements with Asian and

African nations. Governor Huntsman holds a BA in international politics from the University

of Pennsylvania.

Craig R. Barrett is a leading advocate for improving education in the United States and around

the world. He is also a vocal spokesman for the value technology can provide in raising social and

economic standards globally. Dr. Barrett joined Intel Corporation in 1974 and held the positions

of vice president, senior vice president, and executive vice president from 1984 to 1990. In 1992, he

was elected to Intel Corporation’s Board of Directors and was promoted to chief operating ocer

in 1993. Dr. Barrett became Intel’s fourth president in 1997, chief executive ocer in 1998, and

21

UPDATE TO THE IP COMMISSION REPORT

chairman of the board in 2005, a post he held until May 2009. He has served on numerous other

boards as well as on policy and government panels. Until June 2009, he was chairman of the United

Nations Global Alliance for Information and Communication Technologies and Development,

which works to bring computers and other technology to developing parts of the world.

Dr. Barrett has also been an appointee of the president’s Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and

Negotiations and the American Health Information Community. He has co-chaired the Business

Coalition for Student Achievement and the National Innovation Initiative Leadership Council, and

has served as a member of the Board of Trustees for the U.S. Council for International Business